Entries in energy (96)

Western Hemisphere's Shale Men as Oil Industry's New "World Swing Producers"?

Wednesday, February 24, 2016 at 3:20PM

Wednesday, February 24, 2016 at 3:20PM

FASCINATING BRIEFING IN A RECENT ECONOMIST (23 JAN 16) ADDS A NEW TWIST TO AN ARGUMENT I'VE BEEN RECENTLY ADVANCING ON HOW NORTH AMERICA'S EMERGING ENERGY INDEPENDENCE DRAMATICALLY REDEFINES ITS OWN SENSE OF ECONOMIC RESILIENCE AND – ULTIMATELY – AMERICA'S GLOBAL SECURITY PERSPECTIVE. Think of the future as mostly about energy and water, with the latter accounting for food production. Any country seeking to ensure its economic resilience going forward wants to be either rich in both, or rich in secure access to both. This is essentially where China is weakest now and in coming decades (hence the aggressive military behavior on display off its coast), because it must import both food and energy in ever increasingly amounts (and overwhelmingly via seaborne trade). This is also where America (and North America in general) is strongest now and in coming decades, relative to just about every great power out there – save perhaps Russia. But even there, America has little reason to unduly worry about the widely-perceived renewal of strategic rivalry with Moscow, which invariably becomes China's economic vassal on that basis:

China, please meet Russia, an energy-business-masquerading-as-a-government, which is incredibly vulnerable on the subject of lower energy prices but stands as the world's largest exporter of energy.

Russia, please meet China, which is the world's largest importer of energy and the stingiest, most aggressively demanding trade partner in the world.

Please go about you co-dependency with all the respect and friendship that you've each bestowed upon the other's culture and civilization over the years.

As I've pointed out, North America is already the world's de facto swing producer on grains, which gives us an enormous strategic advantage – and power – that we scarcely realize.

We are, in effect, the Saudi Arabia of grain. So, if, in our imagination, they have the world over an oil barrel, then we've got the world over a breadbasket.

Guess who cries "uncle" first?

And yes, we'll maintain that status in spite of climate change, because we're that clever and that resilient and that blessed by circumstances.

But here's where the Economist's analysis of the recent slide in oil prices is so intriguing: what if North America were to become the world's swing producer on energy – as well?

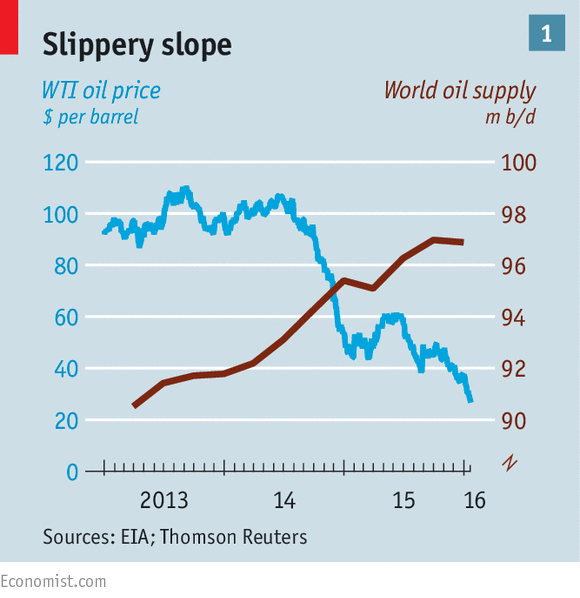

Now the fear for producers is of an excess of oil, rather than a shortage. The addition to global supply over the past five years of 4.2m barrels a day (b/d) from America’s shale producers, although only 5% of global production, has had an outsized impact on the market by raising the prospects of recovering vast amounts of resources formerly considered too hard to extract. On January 19th the International Energy Agency (IEA), a prominent energy forecaster, issued a stark warning: “The oil market could drown in oversupply.”

Amazing what the fracking revolution in North America has wrought, and don't – for a minute – discount how that sense of energy independence influenced President Obama's decision to see a Nixon-like detente with Iran, identified in the piece as "the most immediate cause of the bearishness."

[Iran] promises an immediate boost to production of 500,000 b/d, just when other members of OPEC such as Saudi Arabia and Iraq are pumping at record levels. Even if its target is over-optimistic, seething rivalry between the rulers in Tehran and Riyadh make it hard to imagine that the three producers could agree to the sort of production discipline that OPEC has used to attempt to rescue prices in the past.

But it gets even more disruptive – again, because of the fracking revolution in North America:

Even if OPEC tried to reassert its influence, the producers’ cartel would probably fail because the oil industry has changed in several ways. Shale-oil producers, using technology that is both cheaper and quicker to deploy than conventional oil rigs, have made the industry more entrepreneurial. Big depreciations against the dollar have helped beleaguered economies such as Russia, Brazil and Venezuela to maintain output, by increasing local-currency revenues relative to costs. And growing fears about action on climate change, coupled with the emergence of alternative-energy technologies, suggests to some producers that it is best to pump as hard as they can, while they can.

So we witness the Saudis – yet again – trying to shake out the market, not to mention its fierce regional rival, through an extended period of self-destructive over-production relative to market demand. It will definitely hinder Iran's re-entry into the world and its energy market, but in the US?

Yet there is also a reason for keeping the pumps working that is not as suicidal as it sounds. One of the remarkable features of last year’s oil market was the resilience of American shale producers in the face of falling prices. Since mid-2015 shale firms have cut more than 400,000 b/d from output in response to lower prices. Nevertheless, America still increased oil production more than any other country in the year as a whole, producing an additional 900,000 b/d, according to the IEA.

And here's where US technological resilience gets truly interesting:

During the year the number of drilling rigs used in America fell by over 60%. Normally that would be considered a strong indicator of lower output. Yet it is one thing to drill wells, another to conduct the hydraulic fracturing (“fracking”) that gets the shale oil flowing out. Rystad Energy, a Norwegian consultancy, noted late last year that the “frack-count”, ie, the number of wells fracked, was still rising, explaining the resilience of oil production.

The roughnecks used other innovations to keep the oil gushing, such as injecting more sand into their wells to improve flow, using better data-gathering techniques and employing a skeleton staff to keep costs down. The money is no longer flowing in. America’s once-rowdy oil towns, where three years ago strippers could make hundreds of dollars a night from itinerant oilmen, are now full of abandoned trailer parks and boarded-up businesses. But the oil is still flowing out. Even some of the oldest shale fields, such as the Bakken in North Dakota, were still producing at the same level in November as more than a year before.

No, we don't want to overestimate the economic boost to the US economy from all this. Our economic restructuring challenges are significant – as evidenced by voter anger in this year's presidential race. But others have it far worse:

Unsurprisingly some of the biggest splashes of red ink in the IMF’s latest forecast revisions were reserved for countries where oil exploration and production has played a significant role in the economy: Brazil, Saudi Arabia, Russia (and some of its oil-producing neighbours) and Nigeria. Weaker demand in this group owes much to strains on their public finances.

Russia has said it will cut public spending by a further 10% in response to the latest drop in crude prices (see article).

So where do we go from here? The article discusses "peak demand," something I've long argued would naturally precede the much-feared "peak oil" moment, primarily due to efficiency and environmental concerns.

Then the Economist lays out the crown-jewel argument – from my perspective – of the piece:

More likely, the oil price will eventually find a bottom and, if this cycle is like previous ones, shoot sharply higher because of the level of underinvestment in reserves and natural depletion of existing wells. Yet the consequences will be different. Antoine Halff of Columbia University’s Centre on Global Energy Policy told American senators on January 19th that the shale-oil industry, with its unique cost structure and short business cycle, may undermine longer-term investment in high-cost traditional oilfields. The shalemen, rather than the Saudis, could well become the world’s swing producers, adding to volatility, perhaps, but within a relatively narrow range.

Bingo!

Please keep that in mind when all the politicians and national security experts are trying to scare you to death during our ongoing transition from one president to the next: when it comes to food/water and energy, North America – and America in particular – is sitting pretty.

Why?

Because our national resilience on both continues to contradict the pessimists while amazing even the optimists like me!

China,

China,  Iran,

Iran,  Russia,

Russia,  US,

US,  agriculture,

agriculture,  energy,

energy,  global trends,

global trends,  global warming,

global warming,  resilience | in

resilience | in  Citation Post |

Citation Post |  Email Article |

Email Article |  Permalink |

Permalink |  Print Article

Print Article There Are No Development Short-Cuts, But You Can Compress the Costs - the Energy Example

Wednesday, February 10, 2016 at 1:38PM

Wednesday, February 10, 2016 at 1:38PM

This is a subject upon which I've long harped as an apostle of the true faith in capitalism: the average person in the Developing South wants all the same things we've long enjoyed in the Developed North, so – duh(!), they're not interested in pathways that continue to delay that glorious achievement, particularly when it comes to foregoing economic advance in the name of keeping their local environments "pristine" to make up for the fact that we in the North totally altered ours when grabbing for all the wealth and comforts we now enjoy. Simply put, they have no desire to pay for our "sins."

Indeed, the most notorious types in the global South who embrace this self-denial "imperative" offered by the North are the very same civilizational fundamentalists whom we now so clearly fear for their tendency to go religiously rogue in championing the mass murder of "infidels" by any means necessary. That nasty crew is more than happy to go back to the 7th-century paradise when men were nasty, brutish, and short, and women and children were just this side of sex slaves and chattel (and no, the historian in me doesn't allow me to add the word "respectively" to the end of that sentence). If you want to see what truly constitutes preservation of the developmental pristine, spend some time within the Islamic State (Iraq, Syria) or the ranks of Boko Haram (northeast Nigeria) and al-Shabaab (south/central Somalia). There is nothing noble in their rejection of a consumer society and all the "dangerous" liberties it presents.

What we truly know from history is that people – the world over – become more tolerant, better stewards, and more socially charitable oncetheir incomes rise to the point where they're no longer obsessed with their personal/family's/clan's survival. Just those first couple of steps up Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs and – man(!) – does humanity's innate capacity for empathy surmount darn near all, unleashing the social resilience that has defined our species' mastery of this planet.

It just takes a wee bit of strategic patience on our part (hard for us Northerners so long used to getting every material and emotional need almost instantly met), or an acceptance that economic development, while it can be sped up, isn't subject to short-cuts, much less magical leaps.

Now to Lomborg's recent op-ed on the subject of what we should or should not expect Africans to do to atone for our past mistakes/gluttony/greed for a better life, while they seek the same for themselves (I know, how dare they!):

Africa is the world’s most “renewable” continent when it comes to energy. In the rich world, renewables account for less than a tenth of total energy supplies. The 900 million people of Sub-Saharan Africa (excluding South Africa) get 80% of their energy from renewables ...

Ah, the "noble savage" who can teach all us "lost souls" how to reconnect to nature, except ...

All this is not because Africa is green, but because it is poor. Some 2% of the continent’s energy needs are met by hydro-electricity, and 78% by humanity’s oldest “renewable” fuel: wood. This leads to heavy deforestation and lethal indoor air pollution, which kills 1.3 million people each year.

Nobody wants to hear this, but humanity's journey through phases of economic development has progressively de-carbonized our energy sources, moving us from wood (don't even ask) to coal (high CO2 emissions) to oil (lower) to natural gas (still lower) to (God forbid!) nuclear (very low) and ultimately hydrogen (way low if generated by nuclear power plants). Thus, to be pristine is to be incredibly dirty – by today's environmental standard.

But let's skip all that, say the visionaries ...

What Africa needs, according to many activists, is to be dotted with solar panels and wind turbines ...

Right on! Fast-forward to the good parts! Like we finally figured out how to do – emphasis on the word finally:

Europe and North America became rich thanks to cheap, plentiful power. In 1800, 94% of all global energy came from renewables, almost all of it wood and plant material. In 1900, renewables provided 41% of all energy; even at the end of World War II, renewables still provided 30% of global energy. Since 1971, the share of renewables has bottomed out, standing at around 13.5% today. Almost all of this is wood, with just 0.5% from solar and wind.

Weird fact: the most developed countries in the world today tend to be the most environmentally "clean," while the least developed tend to be the most trashed. The big difference: people with money have the option to care.

Weird fact: the most developed countries in the world today tend to be the most environmentally "clean," while the least developed tend to be the most trashed. The big difference: people with money have the option to care.

So what should we reasonably demand of Africa? After all, it's home to droughts and famine that would rival America's Arizona – if the latter wasn't populated with retirees with enough wealth to make both problems go away with the swipe of a card.

... By 2040, in the IEA’s optimistic scenario, solar power in Sub-Saharan Africa will produce 14kWh per person per year, less than what is needed to keep a single two-watt LED permanently lit. The IEA also estimates that renewable power will still cost more, on average, than any other source – oil, gas, nuclear, coal, or hydro, even with a carbon tax ...

Oh my. Still, wouldn't it be more fair to ask Africans to forego all that dehumanizing consumption for a simpler, more satisfying – and admittedly far shorter – life? Lomborg suggests "no":

Few in the rich world would switch to renewables without heavy subsidies, and certainly no one would cut off their connection to the mostly fossil-fuel-powered grid that provides stable power on cloudy days and at night (another form of subsidy). Yet Western activists seem to believe that the world’s worst-off people should be satisfied with inadequate and irregular electricity supplies.

I believe we call that "living off the grid," and doesn't that make you a better and happier person?

In its recent Africa Energy Outlook, the IEA estimates that Africa’s energy consumption will increase by 80% by 2040; but, with the continent’s population almost doubling, less energy per person will be available...

Providing more – and more reliable – power to almost two billion people will increase GDP by 30% in 2040. Each person on the continent will be almost $1,000 better off every year.

Hmm. That sounds like they'll just be lost to the "rat race" of modern consumerism (he sanctimoniously intoned, pecking away at his $1,000 laptop in his toasty-warm Madison Wisconsin home mid-winter).

But what about the costs of his selfish hedonism?

In other words, the total costs of the “African Century,” including climate- and health-related costs, would amount to $170 billion. The total benefits, at $8.4 trillion, would be almost 50 times higher.

The same general argument probably holds for India and other developing countries . . .

Annoying, isn't he?

But let's be clear about his argument, brushing aside the usual straw-man criticism that he cares not for the environment:

One day, innovation could drive down the price of future green energy to the point that it lifts people out of poverty more effectively than fossil fuels do. Globally, we should invest much more in such innovation. (emphasis mine) But global warming will not be fixed by hypocritically closing a path out of poverty to the world’s poor.

Just think about how much we in the North now naturally obsess over our own perceived lack of resilience or brittleness in the face of today's global complexity, uncertainty, and challenges. And then imagine doing that on a dirt floor in a one-room hut in rural southern Ethiopia while you breath in the fumes from your dung-fueled cookstove.

Which sounds easier to you?

We all want to manage this world with greater care, more foresight, and kind accommodation of each another's basic and higher needs. And we will get there, increasing our collective resilience as we go. We just won't take any shortcuts, nor leave anybody behind - much less ask them to do so to make up for our past transgressions.

Africa,

Africa,  development,

development,  energy,

energy,  environment | in

environment | in  Citation Post |

Citation Post |  Email Article |

Email Article |  Permalink |

Permalink |  Print Article

Print Article YouTubes of 2015 Washington DC speech

Monday, January 18, 2016 at 10:37AM

Monday, January 18, 2016 at 10:37AM Video segments of September 2015 briefing to an international military audience in the Washington DC area.

Part 1: Introductions and US grand strategy

Part 2: America's looming energy self-sufficiency

Part 3: Climate Change and its impact on food & water

Part 4: The aging of great powers

Past 5: Millennials & Latinization of U.S.

Part 6: Evolution of US Military under Obama

Part 7: Dangers of a "splendid little war" with China

Part 8: Middle East without a Leviathan

Part 9: Answers to audience questions

A Troubling Start to 2016 and Global Energy Security

Monday, January 4, 2016 at 3:03PM

Monday, January 4, 2016 at 3:03PM  NBC News CRUDE OIL PRICES ARE PRESENTLY TESTING HISTORIC LOWS, WITH "NEW" IRANIAN OIL SET TO HIT THE MARKET IN 2016. In general, that's good news for a global economy that's greatly benefited from lower energy prices thanks to the North American-led fracking revolution in tight oil and shale gas production. That production growth has allowed the US to continue to cut its crude oil imports, thus allowing major Persian Gulf exporters to further concentrate on meeting South and East Asia's ever growing demand.

NBC News CRUDE OIL PRICES ARE PRESENTLY TESTING HISTORIC LOWS, WITH "NEW" IRANIAN OIL SET TO HIT THE MARKET IN 2016. In general, that's good news for a global economy that's greatly benefited from lower energy prices thanks to the North American-led fracking revolution in tight oil and shale gas production. That production growth has allowed the US to continue to cut its crude oil imports, thus allowing major Persian Gulf exporters to further concentrate on meeting South and East Asia's ever growing demand.It's no mere coincidence that America's willingness to play "global policeman" in the Persian Gulf has declined commensurately with its growing energy self-sufficiency. Yes, war-weariness was the proximate cause for Washington's strategic disengagement from the region under President Obama, who packaged that move as a necessary "strategic pivot" from Southwest Asia to East Asia so as to counter China's growing military "muscle flexing." But that was why Obama was elected - twice. As we've seen with the Paris terror strikes of weeks back, a Western great power (France) can easily find itself sucked back into the Middle East's many battlefields, so Americans should not delude themselves into thinking that such renewed pacifism is permanent. The right constellation of terror strikes in the US could easily push the next president (Clinton? Trump? Rubio?) into more vigorous action, no matter how much the Pentagon prefers to plan its high-tech future wars against more conventional opponents (Russia, China). I mean, sometimes America's foreign policy happens to the world, and sometimes the world happens to America's foreign policy.

Ultimately, however, it will more likely be America's rising energy self-sufficiency that dissuades Washington from reassuming a lead balancing/stabilizing military role in the Persian Gulf - that, and the rise of the Millennial Generation as a force in American politics (hint, they don't see China as an enemy and greatly prefer multilateralism over unilateralism).

But here's the trick: even as it is China, India, Japan and South Korea that import the vast majority of Persian Gulf oil (from Saudi Arabia, Iraq, Iran), none of them show much interest in replacing the US with its Carter Doctrine notion (now fading) of keeping the Gulf open and available to the global energy trade. Frankly, the only great power that seems to harbor such ambitions is Russia, with its surprise entry into Syria's civil war. Yes, China just signed a naval basing agreement with Djibouti on Africa's nearby "horn," but Beijing's interests seem decidedly limited to protecting its energy shipping versus playing a direct role in tamping down the region's many bitter rivalries - any one of which could directly impact global energy security.

So that's why today's headlines about Saudi Arabia once again breaking off diplomatic ties with regional rival Iran are seriously disturbing.

Saudi Arabia severed diplomatic relations with Iran on Sunday, escalating the regional crisis that erupted after the execution of a Shiite cleric triggered outrage among Shiites across the Middle East and beyond.

Saudi Foreign Minister Adel al-Jubeir told reporters in Riyadh that the Iranian ambassador to Saudi Arabia had been given 48 hours to leave the country, citing concerns that Tehran’s Shiite government was undermining the security of the mostly Sunni kingdom.

Saudi diplomats had already departed Iran after angry mobs trashed and burned the Saudi Embassy in Tehran overnight Saturday, in retaliation for the execution of Sheik Nimr Baqr al-Nimr earlier in the day.

The rift sets the region’s two biggest powerhouses on a collision course at a critical time for U.S. diplomacy aimed at bringing peace to the Middle East, and it raises the specter of worsening violence in countries where they back rival factions, such as Yemen and Syria.

Despite their countless international feuds, it was the first time since a two-year rupture in 1988-1990 that diplomatic relations between Iran and Saudi Arabia had formally been severed, according to Abdullah al-Shamri, a Saudi analyst and former diplomat.

To put it in perspective, an equivalent scary development in East Asia would require a similar severing of ties between China and Japan over South/East China Sea maritime disputes. That's because the biggest and most important commodity flow in the global economy today is Persian Gulf crude oil flowing from Southwest Asia to South and East Asia by sea. That flow can be disrupted at its source or at its destination, but either way, any such crisis would be highly destabilizing.

We in the West have long assumed that the big flow was from the PG to us, but that reality dissipated a long time ago. The Persian Gulf is the 5th most-important source of US crude oil after (1) domestic production, (2) North America (Canada, Mexico) imports, (3) South American imports (historically Venezuela but Brazil will emerge over time), and (4) African sources. Somebody blows up the Persian Gulf tomorrow and - in direct terms - it's a speed bump for the US economy. It would, however, bring Asia's economic pillars to their knees rather quickly, which, in turn, would harm the rest of the global economy in due course.

So yes, we in the West should be very concerned by Iran and Saudi Arabia's long-running and highly bitter rivalry breaking out in the open so decisively right now. We don't actually live in a "G-Zero world" (the notion that none of the G-20 powers is interested in managing the international system right now). Russia wants to manage it's "near abroad" alright, and America seeks to manage East Asia with its "pivot" there, to match China's clear ambitions to do the same. It's just that no one seems all that interested - save for meddling Putin - in doing the same for the tumultuous and tense Persian Gulf.

And that's a scary way to start 2016.

Core-Gap,

Core-Gap,  energy | in

energy | in  Tom in the media,

Tom in the media,  Tom's speaking engagments |

Tom's speaking engagments |  Email Article |

Email Article |  Permalink |

Permalink |  Print Article

Print Article Shale gas revolution triggers FDI boom for US

Wednesday, December 19, 2012 at 9:02AM

Wednesday, December 19, 2012 at 9:02AM

FT front-page story on shale gas boom in US already identifiably responsible for additional $90b foreign direct investment flow into US.

Subtitles are telling:

- Investments drive US industrial renaissance

- European companies fear growing divide

Industries that benefit from cheap feedstocks are being targeted, and European counterparts fear they will be at systematic disadvantage in any industry that is fuel-intensive.

Yes, some of these same industries in US argue now for no LNG exports, lest the advantage slip away. But most energy experts say we can export at will and probably raise the MMBTU price by maybe only one dollar. We are now about 8-10$ cheaper than LNG prices in Europe and about $15 less than what Asians (mostly the Japanese) are paying.

So yeah, we can have our cake and eat it too.

Forever?

No, but arguably for a solid generation's time.

So much for "peak oil" determining all.

FDI,

FDI,  US,

US,  energy,

energy,  extractive industries | in

extractive industries | in  Citation Post |

Citation Post |  Email Article |

Email Article |  Permalink |

Permalink |  Print Article

Print Article WSJ front-pager on "global gas push" mirrors Wikistrat sim scenario

Thursday, December 6, 2012 at 12:01AM

Thursday, December 6, 2012 at 12:01AM  Per the recent Wikistrat simulation, "North America's Energy Export Boom," we had a scenario called "Fit of Peaks" in which the US "got it right" (fracking revolution) but much of the rest of the world had a hard time cashing in similarly.

Per the recent Wikistrat simulation, "North America's Energy Export Boom," we had a scenario called "Fit of Peaks" in which the US "got it right" (fracking revolution) but much of the rest of the world had a hard time cashing in similarly.

The WSJ front-pager, entitled "Global Gas Push Stalls: Firms Hit Hurdles Trying to Replicate U.S. Success Abroad" fits that model nicely.

Key finding:

Among the reasons for the glacial pace are government ownership of mineral rights, environmental concerns and a lack of infrastructure to drill and transport gas and oil. In addition, much less is known about the geology in most foreign countries than in the U.S., where drilling activity has been going on for more than a century.

The upshot: the U.S. and Canada could remain the main countries to reap the economic advantages of shale development for some time.

The serious advantage: the gas and ethane glut lures petrochem and fertilizer companies to NorthAm to take advantage of the cost differential - "a huge change after years of shifting production abroad."

Bottom line: about a decade head-start for NorthAm.

I speak this morning in Houston at a board meeting of a national offshore industries association member company. This emerging strategic reality is coming to dominate my career right now.

US,

US,  energy,

energy,  extractive industries,

extractive industries,  global trends | in

global trends | in  Citation Post,

Citation Post,  Wikistrat |

Wikistrat |  Email Article |

Email Article |  Permalink |

Permalink |  Print Article

Print Article Getting Arctic hydrocarbons will be a lot harder than anticipated

Friday, November 30, 2012 at 12:01AM

Friday, November 30, 2012 at 12:01AM

FT special report on Canadian energy that highlights the difficulties of accessing Arctic oil and gas and bringing it economically to market.

First is the sheer remoteness. Then there's the extremely hostile environment. Even with the ice-clearing in the summer, the genuine window for exploitation is still measured in weeks. Everything you use must be special built, platforms with extreme reliability.

And the fields in question need to be big - really big - to cover the high costs.

In short, only the majors and supermajors should apply, because only they will have the "financial firepower."

This is all before governments issue ever stringent safety requirements to protect the environment, a bar that rises with each Deepwater Horizon.

Finally, there's how you get it to market, with the big choice being between fixed pipelines and ice-class shuttle tankers. Neither is cheap.

Just a bit of cold water thrown on the anticipated "bonanza."

I note it with interest as I write the final report (while traveling most of the week) for Wikistrat's recent "How the Arctic Was Won" simulation.

Fracking confronts the reality of limited water resources

Thursday, November 29, 2012 at 12:01AM

Thursday, November 29, 2012 at 12:01AM

WSJ piece noting that all this hydralic fracturing (fracking) is coming up against local water limits. Already, US fracking uses water on par with the city of Chicago or Houston.

So the industry jumps into figuring out how to reuse the water multiple times by cleaning it up (not enough for drinking but enough to reuse). Already in PA the percentage use of recycled water is up to 17% this year, jumping from 13% last year.

This is a huge issue, because we're looking at 1 million more fracking wells globally by 2035, according to Schlumberger (oilfield services co.). The issue is expressed both in unwanted externalities (enviro risks/damage) and cost within the industry (acquiring and disposing).

Something to keep an eye on, as the industry competes with Mother Nature (climate change), agriculture and urbanization globally.

Saudi America

Friday, November 16, 2012 at 11:11AM

Friday, November 16, 2012 at 11:11AM Title of the WSJ's lead editorial on Tuesday.

Two charts displaying the tectonic shift afforded by fracking technology.

This, plus fiscal constraints, makes for a new definition of US superpower-dom.

Let the debate begin ...

Let the debate begin ...

Charts of the day: Saudi Arabia's options

Wednesday, October 10, 2012 at 10:07AM

Wednesday, October 10, 2012 at 10:07AM

Nice full-page analysis at FT on how the Saudis have worked hard to give themselves a response option if Iran attempts to close Hormuz (far harder than imagined).

The relevant bit:

Earlier this year, Riyadh and Abu Dhabi opened new pipelines that will increase the ability of countries to bypass the strait. Fully operational, 6.5m barrels per day, or about 40 per cent of total flows, will now be able to take alternative routes. “The Middle East is much better prepared now than a year ago to cushion the impact of a disruption in the Strait of Hormuz,” says Edward Morse, head of commodities research at Citigroup and former US deputy assistant secretary of state for international energy policy.

The key number is the Saudi one. The kingdom has managed to siphon off half their exports to other vectors.

Then look at who's at risk. US imports only 42% of its oil, and only 16% of that comes through straits, so only about 7% of US imported oil comes through straits, or roughly 3% of total US oil usage comes through straits. Of total US energy usage, that's just under 1.5%.

So no, the US won't be crippled when Hormuz gets shut down - as unlikely as that feat would be for Iran.

China,

China,  India,

India,  Iran,

Iran,  Japan,

Japan,  Middle East,

Middle East,  US,

US,  energy |

energy |  Email Article |

Email Article |  Permalink |

Permalink |  Print Article

Print Article Culprit #2 for U.S. coal industry: China's economic slowdown

Thursday, October 4, 2012 at 9:07AM

Thursday, October 4, 2012 at 9:07AM

From a WSJ front-page story.

The U.S. coal industry wants you to believe its slowdown is caused by Washington's "meddlesome regulations," but as I noted earlier, the big killer is the cheap price of U.S. natural gas, which is displacing domestic use of coal for electricity generation big-time (25% down in a recent quarter).

Culprit #2 is the Chinese economic slowdown, which is really the culprit, along with Europe's problems, for the slowdown in general global economic activity.

Pretty amazing times, when you think about it. Remember when the U.S. economy was all you needed for a global expansion?

Charts of the day: the US "oil recovery"

Wednesday, October 3, 2012 at 12:33PM

Wednesday, October 3, 2012 at 12:33PM Alas, our inevitable "Mad Max" future a bit . . . modified.

From a WSJ interview with Daniel Yergin.

Production up (25% since 2008), drilling way up (didn't Obama and the Dems sabotage all that?), and imports falling. US demand relatively flat - like Europe's, so the rising production means a substantial drop in import share. Was 60% in 2005, now 42%, and expected to be roughly a third by 2035 (though I think it happens MUCH earlier).

Of course, now we'll never have to fight a war overseas . . .

US,

US,  economy,

economy,  energy,

energy,  extractive industries | in

extractive industries | in  Chart of the day |

Chart of the day |  Email Article |

Email Article |  Permalink |

Permalink |  Print Article

Print Article Where is the world is Wikistrat?

Friday, September 28, 2012 at 12:02AM

Friday, September 28, 2012 at 12:02AM

A graphic listing most - but not all - of the sims conducted by Wikistrat this year. The point is to display the breadth and the volume. Be impressed, because you should be.

Wikistrat's sims aren't a year in the planning. Client names the subject and we're off and running in days. Why? All Wikistrat needs is a framework and then we turn the analysts loose on the scenarios. The company don't spend countless man-hours narrowing down the range of possibilities so that 95% of the uncertainty and surprise is drained from the exercise by the time we actually start it. Wikistrat can customize the structure to your concerns and then it brings the masses in to run with that structure and take it places you - the client - hadn't considered.

That approach allows for a huge mapping of possibilities. You want to find the needle in the haystack? Well, Wikistrat can run through that hay awfully damn quick.

Spend a minute and see if you can guess the four sims that were my ideas . . .

{music}

First one was China as Africa's de facto World Bank. I'm pretty sure that was based on a WSJ headline noting that tipping point. It ended up positing a lot of interesting intersection points between the US and China on the continent. Sim ended up generating both a report and a briefing by me.

Second one was the North American Energy Export Boom. There was a time when Wikistrat asked me what I'd most like to explore in terms of near-term uncertainty in the system, and the whole fracking thing just jumped out at me: Which way does it go? Does it work out big-time for the US and - ultimately - the world? Or does it get aborted like nuclear power for enviro reasons? That was a very strong sim in terms of output, and all that material (final report and my brief) still tracks incredibly well with headlines. All we did is simply systematize all those possibilities, organizing them into four major trajectories (usual X-Y approach). But the upshot was, anybody who goes through that stuff now has the capacity to process all the headlines to come.

Third one was the China slowdown sim. That one's been in my mind since I wrote the piece for Esquire back in the fall of 2010 (it came out in the Jan '11 issue). The idea came to me in the summer of 2010 and it took a while to sell it to the magazine, but it looks fairly prescient today, doesn't it? Anyway, a very solid sim that ran down all manner of possibilities, and I really loved the quartet of scenarios we came up with (which drew comparisons to historical risers). Great report and probably the strongest brief I've yet done for WS.

Fourth one was "when China's carrier entered the Gulf." Wikistrat asked me to generate a host of possible sims way back when, and that was one of them. Just a simple logical progression argument, with the trick being imagining all the possibilities when that inevitability unfolds. Hence the sim, which turned out great, along with a solid report. And this one was only a "mini-sim" by WS standards: just a brainstorming drill on scenarios with a quick follow-up on policy options. Mostly junior analysts, but the output was as good as anything I've seen from the National Intelligence Council - seriously.

Two on the list I didn't really have anything to do with: NATO and Pakistan. First one was driven by a client's curiousity. Second one is just a natural "what if?" Both turned out quite nicely.

The Democratic Peace Theory Challenged sim is another one I did not design, and I will admit that, at first blush, I didn't much care for the subject. I was brought in to work the design and shaped it somewhat, but I truly had low expectations. In truth, those were exceeded by a long shot. The material needed more shaping than usual, because the sim had a theoretical bent, but what I ended up with at the end in the final report was . . . to my surprise . . . quite strong - I mean, present at a poli sci/IR conference strong (or walk into any command and brief strong). It easily could have veered into all sorts of panic mongering, but instead it organized a universe of possibilities very neatly. I was really proud of the overall effort, and it reminded me not to get too judgmental going into sims.

The Syria sim I didn't design, nor did I oversee its operation. That Wikistrat left to junior versions of myself. I was brought in at the end to shape the first draft of the report, and, while I moved things around plenty, the material held up very nicely to my critical eye, which is encouraging. If Wikistrat is going to handle all the volume coming down the pike (contractual relationships are piling up at a daunting rate), then the Chief Analyst position needs to be like that of any traditional RAND-like player: that person needs to be able to shape things a bit at the start and then at the end, but mid-range staff need to be able to herd all those cats and the resulting material. So that one felt like a nice maturation of the process, because, like with any successful start-up, the real challenge isn't marketing but execution.

This graphic, for some sad reason, skips the headlining sim of the year to date: When Israel Strikes Iran. That one I had a lot of fun with, giving it my years-in-the-testing phased approach (initial conditions, trigger, unfolding, peak, glide path, exit, new normal). That approach goes back to my Y2K work and later after-action on the Station Nightclub fire disaster in Rhode Island (done for the local United Way to provide lessons learned on how well the organization responded). That was the most structurally ambitious Wikistrat sim to date and it - unsurprisingly - produced the best material by far. I'd put that final report and brief up against anything the best elements of the US national security establishment could produce . . . naturally at about 20 times the cost and five times the duration of effort.

The graphic also doesn't include the most recent sims. I just finished a final report on The Globally Crystalizing Climate Change Event (one of mine), and, despite the great time projection, I was pleasantly surprised at how well the material holds up in the report. I thought the analysts did a great job there.

Based on that fine crowd performance, Wikistrat pushes the community even harder in the just-wrapping-up sim entitled When World Population Peaks. This one was truly challenging, but my point in designing the sim was almost to purposefully "test out" analysts in the manner of a language-skills oral exam, meaning I wanted something almost too hard for most analysts so as to press both them and the supervising analysts on how they handled it. Think of it like a NASA sim where Control is trying to crash the lunar module. That was a bit stressful, I think, for a lot of the community who participated, but - to me - it was like a nasty cross-country workout (I am assistant coaching my kid's team again for the 8th year in a row and I'm on my third kid) early in the season: bit of a bitch mentally and physically, but it'll pay off down the road.

Yes, Wikistrat does take all its sims - even the training ones - very seriously. If you're not growing then you're dying - simple as that. Start-ups have to have that survival-of-the-fittest mentality and we're talking about a small firm that's come out of nowhere (okay, Israel) in just three years.

So, a nice overview of the year, and it's an impressive body of work. Would you believe me if I told you that all of it was accomplished within a timeframe and with a far smaller budget that one of those bloated wargames that Booz Allen runs for the Pentagon?

Well, if you did, then you'd know why Wikistrat is going to succeed in this cutthroat business.

Africa,

Africa,  China,

China,  Iran,

Iran,  Israel,

Israel,  Syria,

Syria,  US,

US,  energy,

energy,  environment,

environment,  extractive industries | in

extractive industries | in  Wikistrat |

Wikistrat |  Email Article |

Email Article |  Permalink |

Permalink |  Print Article

Print Article Yeah, right. It's Washington regulations that are screwing "clean coal."

Tuesday, September 18, 2012 at 12:04AM

Tuesday, September 18, 2012 at 12:04AM

We all see the commercials: Washington is killing clean coal with its regulations!

Complete and utter bullshit.

The gas glut is killing coal, displacing it for up to a quarter of US electrical production across the latest full quarter.

So now you see power companies even going to the point of idling coal-fired stations (from the WSJ story):

Sammis is one of a growing number of coal-fired plants that were built to run 24 hours a day, seven days a week, but now may run only occassionally because of soft demand for electricity and competition from gas-fired plants that are cheaper to run and cleaner to operate.

Coal, says the piece, has been progressively losing out to shale gas for four years now. It's just gone super-critical over the last year. Cheap gas now is half the cost of coal when it comes to generating electricity.

This is why America is going to be exporting our superior coal to Asia in coming years.

And that will be a good thing.

Asia,

Asia,  US,

US,  energy,

energy,  extractive industries | in

extractive industries | in  Citation Post |

Citation Post |  Email Article |

Email Article |  Permalink |

Permalink |  Print Article

Print Article Chart of the day: Economist's listing of top 15 natural gas resources

Friday, July 20, 2012 at 10:57AM

Friday, July 20, 2012 at 10:57AM

On the unconvential (shale): the usual list that I work with, with the addition of Russia as #3 in world. Most experts don't talk all that much about Russia because, with all their conventional gas, there's not a great need to exploit.

But the real kicker for me in the charts is the bottom right one, which is a stunner: by 2030 the projection that gas, coal and oil all converge in the high 20s as basically equal shares in world primary energy usage. Several stories here:

- Gas displacing coal (not surprising)

- Long slow increase in nat gas production/use

- And then the true stunner of such a huge drop in oil (about 45% in 1970 to high 20s in 2030).

Fascinating stuff.

China,

China,  LATAM,

LATAM,  Russia,

Russia,  US,

US,  energy,

energy,  extractive industries | in

extractive industries | in  Chart of the day |

Chart of the day |  Email Article |

Email Article |  Permalink |

Permalink |  Print Article

Print Article Chart of the Day: the oil sanctions are working on Iran

Friday, July 13, 2012 at 10:17AM

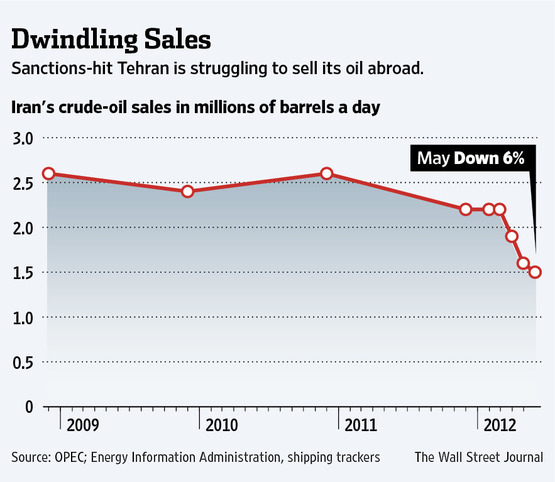

Friday, July 13, 2012 at 10:17AM  Arguably the primary reason why Israel holds off attacking - that and its modest satisfaction with the success of the combination strategy of cyber warfare attacks and assassinations of technical personnel.

Arguably the primary reason why Israel holds off attacking - that and its modest satisfaction with the success of the combination strategy of cyber warfare attacks and assassinations of technical personnel.

You can see that the sanctions have taken about a million barrels a day - or about 40% of daily production denied in terms of sales.

That is significant - and a genuine success for Obama.

The hottest subject in oil deals today involves anybody who has been a regular buyer of Iran. All of these states are looking to replace - now.

And no, they don't all go running to the Saudis.

This chart is a month old. More recent news says roughly 50% drop in May-June alone. Not sure I buy that. Lots of desperate deals happening out there involving Iran. But clearly, the trend is downward and steep.

I honestly do believe that the Arab Spring is helping plenty. With Syria on the ropes, the anti-Iran long knives are out.

India's exploding energy requirements

Thursday, July 5, 2012 at 10:16AM

Thursday, July 5, 2012 at 10:16AM  Good article start, which, in true inverted pyramid fashion, gets all the work done right up front.

Good article start, which, in true inverted pyramid fashion, gets all the work done right up front.

India is facing an energy crisis that is slowing economic growth in the world's largest democracy.

At stake is India's ability to bring electricity to 400 million rural residents—a third of the population—as well as keep the lights on at corporate office towers and provide enough fuel for 1.5 million new vehicles added to the roads each month.

Shortages of coal, oil and natural gas will require India to import increasing amounts of high-cost fossil fuels, say energy experts, risking inflation and putting the country in stepped-up competition with China, Japan and South Korea. Buying oil from Iran, one of India's biggest suppliers, is tougher because of U.S. and European sanctions aimed at curbing Tehran's nuclear ambitions.

With annual demand expected to more than double in the next two decades to the equivalent of six billion barrels of oil, the energy crunch threatens to knock India off its growth path. The national economy has already slowed amid paltry business investment and stalled reforms. It tallied just 5.3% growth in the quarter that ended March 31, the lowest level in almost a decade and well shy of the country's 9% goal.

With annual demand expected to more than double in the next two decades to the equivalent of six billion barrels of oil, the energy crunch threatens to knock India off its growth path. The national economy has already slowed amid paltry business investment and stalled reforms. It tallied just 5.3% growth in the quarter that ended March 31, the lowest level in almost a decade and well shy of the country's 9% goal.

The charts above lay out the problem: Electricity growth is pretty much a proxy for GDP growth. If you want to grow your economy fast, you have to grow your grid capacity similarly. China is getting it done. India is not.

The oil imports stuff is pretty classic for the trajectory: roughly a 5-fold increase since just 2004. I see this growing demand expressed in deals I'm structuring.

But the one that jumped out at me, per the recent Wikistrat sim on "North America's Energy Export Boom," was the coal shortfall now covered by imports. Our sim was mostly about natural gas, of course, but the displacement effect in electricity generation means we have a lot of stranded coal capacity emerging here in the US - coal that could go abroad effectively because it's energy quotient is world class. The story describes recently constructed coal-burning electricity-generation plants that are operating below capacity - or worse, are idled - for lack of coal.

I've seen industry estimates by US coal experts that say India will be a prime source of export growth over the next couple of decades. This article makes clear the "why."

India,

India,  US,

US,  energy,

energy,  extractive industries | in

extractive industries | in  Citation Post,

Citation Post,  Wikistrat |

Wikistrat |  Email Article |

Email Article |  Permalink |

Permalink |  Print Article

Print Article Chart of the day: US natural gas price versus Europe's versus Asia's

Saturday, June 9, 2012 at 10:39AM

Saturday, June 9, 2012 at 10:39AM