Interviewed by Alex Daley

Alex: Hello, I'm Alex Daley. Welcome to another edition of Conversations with Casey. Today our guest is Dr. Thomas Barnett, a famed author and chief analyst at Wikistrat, a massively multiplayer online consulting firm that specializes in bringing war games to public and private clients alike. Thank you, Tom. Can you tell us a little more about your work?

Thomas: Well, Wikistrat is a startup out of Australia by way of Israel. The fact that it comes through Israel is indicative of its focus on taking a product – a service line – and globalizing it rather quickly, early in the process. If you know anything about the startup culture in Israel, it immediately embraces that sort of globalizing ambition.

It's an attempt to create a global community of strategists from around the world and give clients the opportunity – the option – to crowdsource their strategy, rather than have that really tiny group within the organization – and you see this throughout the national security establishment in the United States. If you're in a globalized world, do you want to have two or three white guys sitting in a room, trying to think through China's perspective, India's perspective, Iran's perspective?

[Think of] All the complexity, all the iatrogenic unintended consequences that come from decisions you make in national security or as the head of a corporation. Would you rather have some of your ideas, your strategies, vetted through a much broader lens, a much wider global perspective?

We find that this is a huge cost saver. In many ways, we put together in the Hollywood model temporary teams of analysts from around the world. We war-game in two or three weeks online, 24/7: global community, or whatever strategic concept you want to look at. So we can do it cheaply compared to the classic "butts in seats" model of the consulting firms – the big ones like Booz Allen Hamilton and whatnot – but we can do it fairly rapidly.

If you have an idea, we can put it out, jury-rig it on top of the Wiki; and then we have analysts creating dozens, hundreds, thousands of scenarios if you let it run long enough and have a big enough crowd. You'll get ideas that you just hadn't thought about or considered. So it's fast, it's cheap, and it gets beyond the notion of relying on two or three great minds within your organization to somehow figure out all the complexity on the planet.

Alex: With a network like that, you must get a really interesting perspective on global politics and power and the problems the world is concerned with today. Will you give us some of the examples, some of the insights that you guys have gleaned through your work?

Thomas: Well, we did a war game – or a planning exercise, if you will – on Israel attacking Iran this summer. We came up with a lot of counterintuitive concepts. The further the war goes, for example, the more likely it is that you're really looking at a strategic pivot from that whole dynamic which has dominated American foreign policy the last five, six years, to Turkey sort of running the show in the Middle East. That's because you see an Arab Spring empowering Sunnis throughout the region. You see Iran being threatened by that, acting out more and more, using the whipping boy of Israel to justify its reach for the bomb, when it's really concerned about American regime-change ambitions, rightly or wrongly.

Well, that dynamic can play itself out. We can pitch it all in terms of nuclear proliferation and Shia versus Sunni, or Iran versus Saudi Arabia, or Iran versus Israel and Israel's right to exist, the Palestinian question and all that. That whole thing can blow out in a fairly substantial war. You [end up] looking at, to the surprise of many people, a Middle East once again dominated by an Islamist but yet secular democracy in Turkey. You have Iraq turning in that direction, very possibly Syria falling under Turkey's purview and influence... same with the Muslim brotherhood in Egypt.

We are looking at a very tectonic shift amidst all these things. Our fascination now is on "Is Iran going to get the bomb or not?" We are probably looking at something that's going to take that dynamic, and its centrality in American foreign policy, and just push it off the table. You'll be looking at a Middle East really led by an Islamist Turkey, and that will be a huge shift in the way we view things. That wasn't what we were looking for going into the war game. We weren't naturally assuming we were looking at a strategic shift of players and key influences in the region from what we were used to in terms of Saudi Arabia, Iran, Israel, to Turkey, Iraq, Egypt, Syria. That was something that came out because we didn't structure the war game in such a way that we only had one or two outcomes planned. We really threw it out to a global community of several hundred analysts. As you often find with crowdsourcing, people surprise you with the ideas and the creativity and the ingenuity they display.

Alex: It sounds like it's a Middle East based less on religious fundamentals and more on economic power, if Turkey's going to lead. Does that have any implications on American foreign policy? Are we making the wrong decisions out there? Should the Pentagon be changing its direction, or is the Pentagon well ahead of us and your work?

Thomas: Well, I like my private sector smarter than my public sector. In the public sector I like my politicians smarter than my military. In the national-security community, I like my military smarter than my intelligence. So counterintuitively, I like my intelligence – my spies – kind of dumber compared to everybody else, because if the spies are smarter than the military, it looks like Pakistan. If the military is smarter than the politicians, it looks like the Soviet Union, 1985. If politicians are smarter than the private sector, God help you. It looks more like Europe in terms of its creativity. The situation that they've got there now with the fight over the federal project, as opposed to an America that's led by its private sector…

So, I would say, if I'm looking at the planet, I'm looking at globalization. I'm much more comfortable with the view from America's private sector, for example, on how they view China. I would cite GM's relationship with Shanghai Automotive Industrial Group, SAIC, as probably the model that the US government should be following in its relationship with China. They partnered up with SAIC fifteen years ago. They're trying to grow it in such a way that it becomes a shared partnership. As a result, GM is the biggest seller of cars in Asia. But lo and behold, SAIC wants to grow kind of bigger and out of that partnership. That's a great analogy for the United States and China at this point in history.

Are we getting that from the Pentagon? Absolutely not. We're getting a search for a budgetary floor for the big war force, maybe, and air force, in this new "air-sea battle concept." That's basically taking an old Cold War construct: the Fulda Gap (in Germany) air-land battle. We were going to take on Russian tanks in Germany, and now they have us taking on Chinese submarines and missiles in the South China Sea. Underlying all that is really a seabed contest. If you talk to businessmen, they'll tell you they're going to have to split the difference – they're all going to have to invest. It's going to be massively capital intensive. If you want Shell or anybody to go in there and actually get the hydrocarbons at the bottom of the ocean, even CNOOC or Sinopec (Chinese companies), you can't have people shooting off missiles at each other, arresting fishermen, and having spy trawlers bumping into submarines, and stuff like that.

I think we're at a point in history where the complexity and the spread of American-style globalization – which I think is very much modeled on these United States… We went from a sectional to a continental economy in the late 19th century. I think we are seeing a repeat of a lot of that history, right down to the populism, the angry populism we see around the world today, [which was] very much evident in the United States of the 1880s and 1890s. I think business has a more comfortable, comprehensive, systematic take on what's going on in all that complexity than the politicians or the military types do.

Alex: Is this driven by the fact that businesses really don't care about national borders – they're going to go wherever they can find growth, wherever they can find revenue?

Thomas: It is a function of that, because businesses are more interested in getting transactions, customers, getting the investment in. They like security. They're more willing to split the difference. You layer that spreading reality of all the economic activity and financial flows with what happens to traditional societies when globalization comes in. This is a major theme in my books and in my work throughout my career.

You know, we're seeing traditional societies [facing a] very liberating construct. Basically: "Hey, women should go to school, women should go to the workplace. Maybe you should expect more divorces and less control over women in society if you want to develop and rise as an emerging power." We've seen that time and time again; it's all about liberating women, educating them, putting them into the workforce, delaying sex and pregnancy and marriage, getting a "demographic dividend." There's your economic miracle, repeated time and time again. China's just the latest to do it.

When that comes in, it creates social tumult. When men no longer control women in society, man, you get blowback. You get insurgencies, you get fundamentalists of all stripes rejecting that. That's what’s going on. That's what the politicians see, that's what the military sees and that's what we saw with 9/11. But underlying all that is the transaction growth and the network growth being propagated by the business types. When they come to the South China Sea, they look at it and say, "You know what? This is not a fight about where we draw the line. This is: 'Who's got the money? Can we get enough security? Can we get the investment? Can we access the resources? Will you get a proper profit-sharing model here?'" Well, if it's China rising, Japan's sort of fearful of that. All sorts of social and economic tumult going on. The politicians – it becomes very Manichean in their worldview.

So we have a disjuncture between a business network connectivity that is vast – that really defines globalization – and a time lag in understanding between that universe and what's happening in the political and military realm. There, we're still talking in 20th-century nationalism, "this is my border" kind of stuff. We're still seeing a lot of, I would say, earlier than 20th-century responses in the form of Al Qaeda and other types of fundamentalists who fear the essential liberating mode that is globalization, when it comes to traditional societies.

Alex: So the tumult we're seeing across the Middle East and Asia these days is really just a symptom of these countries following America down the path to prosperity and a growing middle class?

Thomas: It's a symptom of globalization coming to parts of the world that have been off-grid for a long time. Our transactional relationship with the Middle East for the last thirty years has been really pretty bare bones. We give you cash, you give us oil, and we really don't interact a whole lot beyond that.

[Think of it as being like] an American south, pre-Civil War, that dominates cotton markets like the Persian gulf dominates oil markets. The more you come in and allow that connectivity – and it comes in all sorts of networking forums, Facebook, the Internet and all that stuff that we've seen drive a lot of the Arab Spring dynamics to a stunning degree. I mean, no one's in charge – who's making these things happen? We're not quite sure. It's just unfolding. We're seeing a lot of young people move into a kind of strongly oppositional mode against what has been the traditional hierarchies in that part of the world. But at the same time it's frightening to us, because those traditional hierarchies have been maintained largely by suppressing religion and identity. And the conundrum for us is realizing as globalization comes into a traditional place like the Middle East, you're going to see more religion, more nationalism, people are going to want to hold on to identity. Why? Because Facebook and the Internet and social networks and globalization and foreign direct investment and all these things are coming in and transforming societies that have been pretty stable in their social structures for hundreds and hundreds of years.

Alex: Big implications for the world. How can America stay on top in a world like this? Do you think it's realistic that we can continue to maintain our position in the global economy with huge populations now coming into these sort of American-style markets?

Thomas: I think you've got to remember that even though we are a young country, we are the world's oldest and most successful and thus most experienced multinational union. What's going on, on a global scale, we practiced and pioneered on a continental scale in the United States in the latter half of nineteenth century. We went from a Civil War package to an America that dominated the whole continent and had 48 states, roughly, or 45 by the end of the century. That process, all the things that went in to it – the railroad building, the insurgencies, the private security firms, doing stuff on the frontier, the religious revivals – that whole package that we see in America in the latter decades of the nineteenth century, we're watching that experiment writ large on the globe. [That's] primarily because we spent the last seven decades trying to make that economic international liberal trade order come about, defending it and encouraging it. But what that does to us now – in Thomas Friedman's language – is create a level playing field. That means our privileged position [is going to be challenged.] The notion of the American dream in the 1950s came off the weird situation where America was still strong and powerful, and the rest of the world was either underdeveloped or decimated by World War II. We got into this mindset that said, "high school degree, blue-collar, middle-class existence."

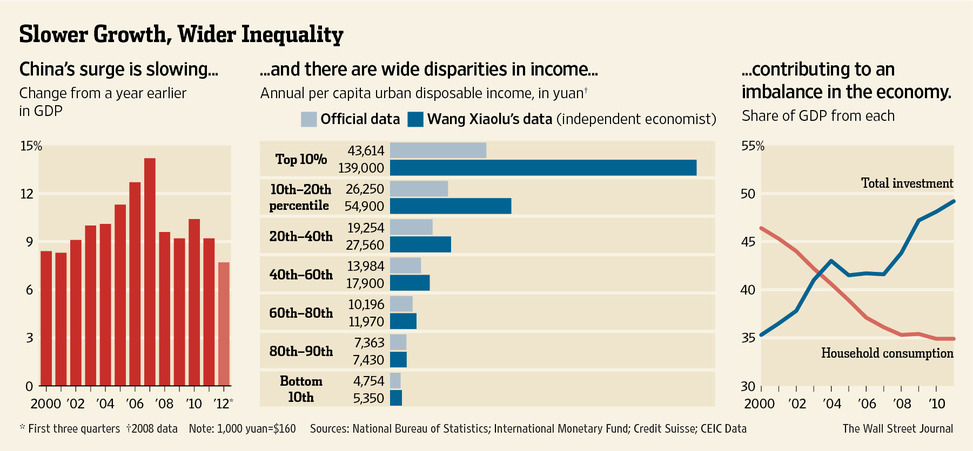

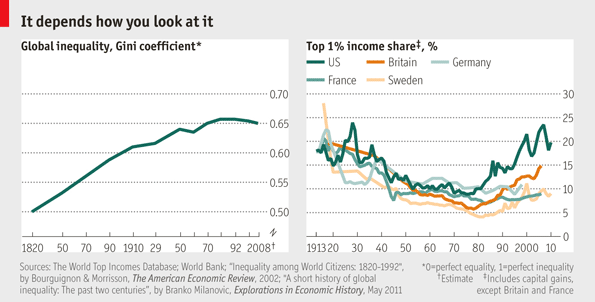

Well, that dream started disappearing within twenty years of its formation in our minds. It is really gone now, to the point where we've experienced an economic boom over the last ten to fifteen years that really didn't, for the first time in history, include income growth for the middle class. If you look at American history, we are democratic, open, and tolerant whenever middle-class incomes are rising. We are intolerant, nondemocratic, and pretty nasty to ourselves and others whenever middle-class incomes stagnate.

India is rising despite a massive Maoist insurgency across the interior. China is booming on the coast, but stagnating in many ways, not developing, still kind of holding to a collectivist mindset in the interior. What's going on between red states, blue states, Tea Party, all that kind of populist anger in America. We're seeing a lot of these same dynamics that we saw in the late 19th century in America. The rise of the global middle class, much like the rise of the American middle class at that time frame – it's a tumultuous process. It's a democratizing process. But anybody who expects that the spread of globalization to bring immediate peace, stability, tranquility – everybody's getting along in a Kumbaya kind of fashion… I mean, that's why I called my first book The Pentagon's New Map. There's going to be tumult and violence, most of it subnational, transnational. Globalization, American-style globalization, is pure social economic revolution.

Alex: That's an incredible change for the world. Does that mean that the next few years are probably going to look a lot more like the last few years then they are the earlier days of American history where we were the one growing economy around the world?

Thomas: Well, we were the China of the late 19th century. And we scared people like China scares people now, and we were kind of a rough, rowdy, corrupt, jingoistic democracy, pretty warlike. And we still have that warlike image in a lot of people's minds, because we've played leviathan to the global system for quite some time. We've been very successful in that. We haven't seen any great power in war across the system for close to 70 years. Part of that's nukes, part of that's America basically saying, "I'm not going to allow that." Well, that role that we've played in the last six, seven decades has given us kind of a privileged sense that we run the world. The problem is, our strategy – our open-door strategy, if you will, of encouraging trade and investment to lead to connectivity, to hopefully, over time, lead to democracy – our success in doing that has created so many rising great powers out there that we're no longer able to boss people around. That creates a certain crisis of confidence in our ability to manipulate the world around us. It forces us to kind of look inward and recognize that there are some big parts of our society and economy that don't work particularly well: health care, education that's still structured in an industrial-era model – that really needs to be revamped if we are going to compete with not just the other players out there in the West but a global middle class that is ravenous in its demands. I mean, changing the resource-utilization models across the planet, but giving us a chance to sell to massively larger numbers of consumers than we've ever had in this world.

It's a great time for us to reinvent ourselves. I look to a future that's in my mind logically, say, 2030 and beyond, dominated by a China, India, and America. I call it my "CIA model of the future," kind of three great superpowers. We are more likely to get to 2030 in great shape, compared to a China that has to democratize and create an environmental movement to really deal with the way it's raping its own ecosystem and using up its water tables. Same for an India that has to deal with all sorts of tumult and a caste system that still residually exists throughout.

We've processed populist anger in America three or four times throughout our history. As much as we like to demean our own democracy, we're actually pretty good at dealing with this kind of change. I give us much better odds than India or China, especially when you realize that compared to them we are chock full of cheap energy.

The fracking revolution reminds us and gives us that possibility again. And then we are, frankly, the OPEC of food, which is an unknown in most people's minds here in America. We are the source – North America writ large – of 70% of the world's moveable feast in terms of poultry, pork, the major grains, beef as well. We are an immense player in that realm; and when you layer on climate change, which is mostly going to be an equatorially centric phenomenon – massive droughts, much more difficulty with water shortages – we have a fairly long-term bright future. We're going to be able to grow food. We're going to have cheap energy. We've got an innovative economy. We've just a couple small things to fix, relative to India and China: health care and education.

We get some serious political leaders willing to do that – which to me probably involves the boomers retiring from politics, because they've proven to be just about the worst political generation we've had in a century – and I think most of these things are quite fixable. We're looking at a major industrial renaissance in America. We're looking at a rebound that will put us back up on top, to the point where I think you can legitimately argue a second American century, very likely. Not the same package we had in the second half of the twentieth century. We won't get to rule by default, but I think there are attributes to this system that put us in a great leadership potential situation for the next five or six decades, easy.

Alex: That's a fascinating insight on the way the world is working, and quite an interesting picture for America, which I think is different than many people paint today. I want to thank you for giving us your unique perspective on the world.

Thomas: Thank you.

Wednesday, October 31, 2012 at 8:11AM

Wednesday, October 31, 2012 at 8:11AM