by Thomas P.M. Barnett

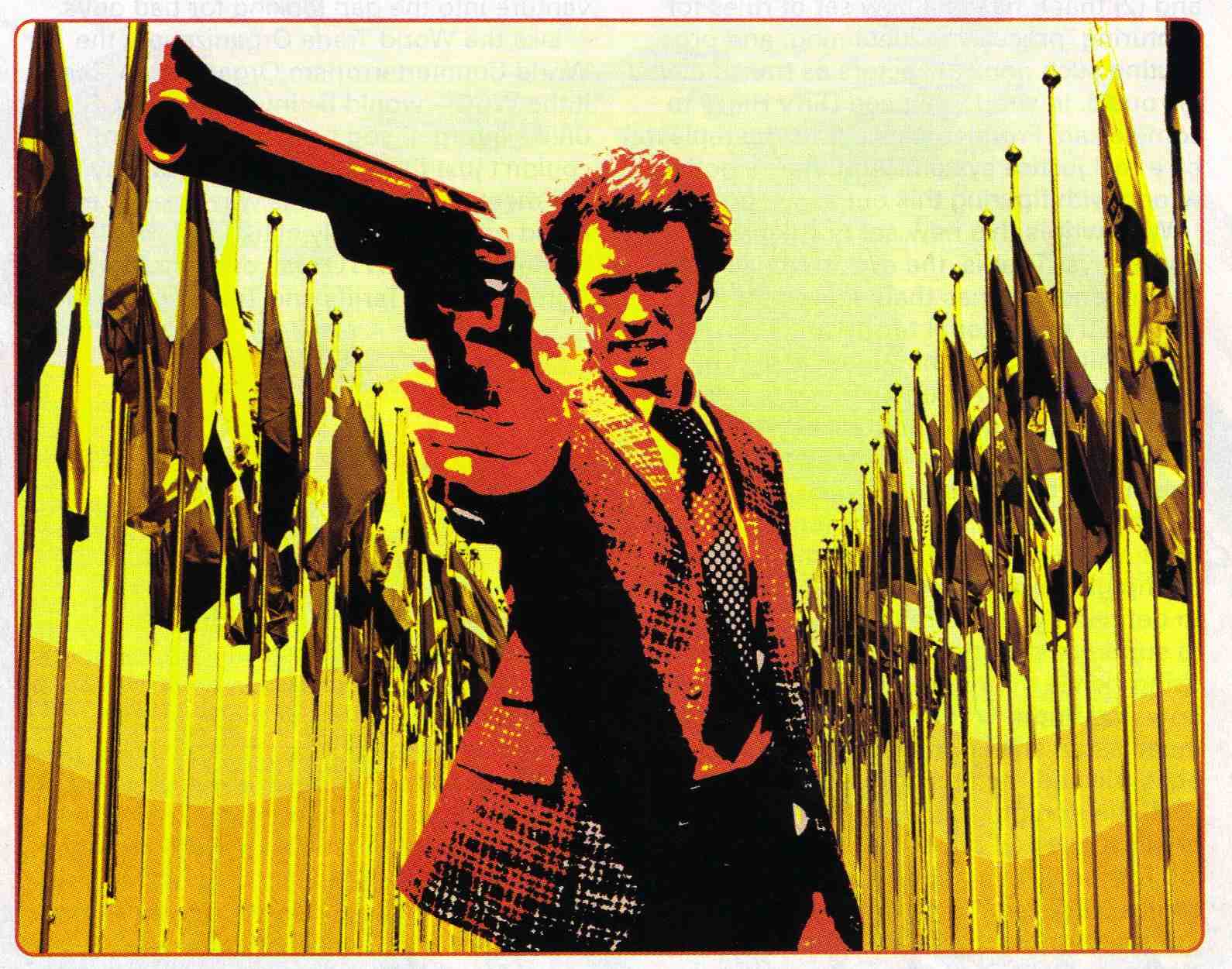

Photographs by Peter Yang

Esquire, April 2008, pp. 144-53.

As head of U.S. Central Command, Admiral William "Fox" Fallon is in charge of American military strategy for the most troubled parts of the world, including the entire Middle East. As hawks in Congress and at the Pentagon planned for war with China, Fallon instead urged cooperation with the Chinese. And now, as the White House has been escalating the war of words with Iran, and seeming more determined to strike militarily before the end of this presidency, the admiral has instead urged restraint and diplomacy. In the end, who will prevail, the president or the admiral?

1.

If, in the dying light of the Bush administration, we go to war with Iran, it'll all come down to one man. If we do not go to war with Iran, it'll come down to the same man. He is that rarest of creatures in the Bush universe: the good cop on Iran, and a man of strategic brilliance. His name is William Fallon, although all of his friends call him "Fox," which was his fighter-pilot call sign decades ago. Forty years into a military career that has seen this admiral rule over America's two most important combatant commands, Pacific Command and now United States Central Command, it's impossible to make this guy -- as he likes to say -- "nervous in the service." Past American governments have used saber rattling as a useful tactic to get some bad actor on the world stage to fall in line. This government hasn't mastered that kind of subtlety. When Dick Cheney has rattled his saber, it has generally meant that he intends to use it. And in spite of recent war spasms aimed at Iran from this sclerotic administration, Fallon is in no hurry to pick up any campaign medals for Iran. And therein lies the rub for the hard-liners led by Cheney. Army General David Petraeus, commanding America's forces in Iraq, may say, "You cannot win in Iraq solely in Iraq," but Fox Fallon is Petraeus's boss, and he is the commander of United States Central Command, and Fallon doesn't extend Petraeus's logic to mean war against Iran.

So while Admiral Fallon's boss, President George W. Bush, regularly trash-talks his way to World War III and his administration casually casts Iranian president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad as this century's Hitler (a crown it has awarded once before, to deadly effect), it's left to Fallon -- and apparently Fallon alone -- to argue that, as he told Al Jazeera last fall: "This constant drumbeat of conflict...is not helpful and not useful. I expect that there will be no war, and that is what we ought to be working for. We ought to try to do our utmost to create different conditions."

What America needs, Fallon says, is a "combination of strength and willingness to engage."

Those are fighting words to your average neocon -- not to mention your average supporter of Israel, a good many of whom in Washington seem never to have served a minute in uniform. But utter those words for print and you can easily find yourself defending your indifference to "nuclear holocaust."

How does Fallon get away with so brazenly challenging his commander in chief?

The answer is that he might not get away with it for much longer. President Bush is not accustomed to a subordinate who speaks his mind as freely as Fallon does, and the president may have had enough.

Just as Fallon took over Centcom last spring, the White House was putting itself on a war footing with Iran. Almost instantly, Fallon began to calmly push back against what he saw as an ill-advised action. Over the course of 2007, Fallon's statements in the press grew increasingly dismissive of the possibility of war, creating serious friction with the White House.

Last December, when the National Intelligence Estimate downgraded the immediate nuclear threat from Iran, it seemed as if Fallon's caution was justified. But still, well-placed observers now say that it will come as no surprise if Fallon is relieved of his command before his time is up next spring, maybe as early as this summer, in favor of a commander the White House considers to be more pliable. If that were to happen, it may well mean that the president and vice-president intend to take military action against Iran before the end of this year and don't want a commander standing in their way.

And so Fallon, the good cop, may soon be unemployed because he's doing what a generation of young officers in the U.S. military are now openly complaining that their leaders didn't do on their behalf in the run-up to the war in Iraq: He's standing up to the commander in chief, whom he thinks is contemplating a strategically unsound war.

It's not that Fallon is risk averse -- anything but. "When I look at the Middle East," he says late one recent night in Afghanistan, "I'd just as soon double down on the bet."

When Fallon is serious, his voice is feathery and he tends to speak in measured koans that, taken together, say, Have no fear. Let Washington be a tempest. Wherever I am is the calm center of the storm.

And Fallon is in no hurry to call Iran's hand on the nuclear question. He is as patient as the White House is impatient, as methodical as President Bush is mercurial, and simply has, as one aide put it, "other bright ideas about the region." Fallon is even more direct: In a part of the world with "five or six pots boiling over, our nation can't afford to be mesmerized by one problem."

And if it comes to war?

"Get serious," the admiral says. "These guys are ants. When the time comes, you crush them."

2.

It was Rumsfeld's fall that led to Fallon picking up his greatest and, inevitably, final mission. Smart guy that he is, Robert Gates, the incoming secretary of defense, finagled Fallon out of Pacific Command, where he'd been radically making peace with the Chinese, so that he could, among other things, provide a check on the eager-to-please General David Petraeus in Iraq.

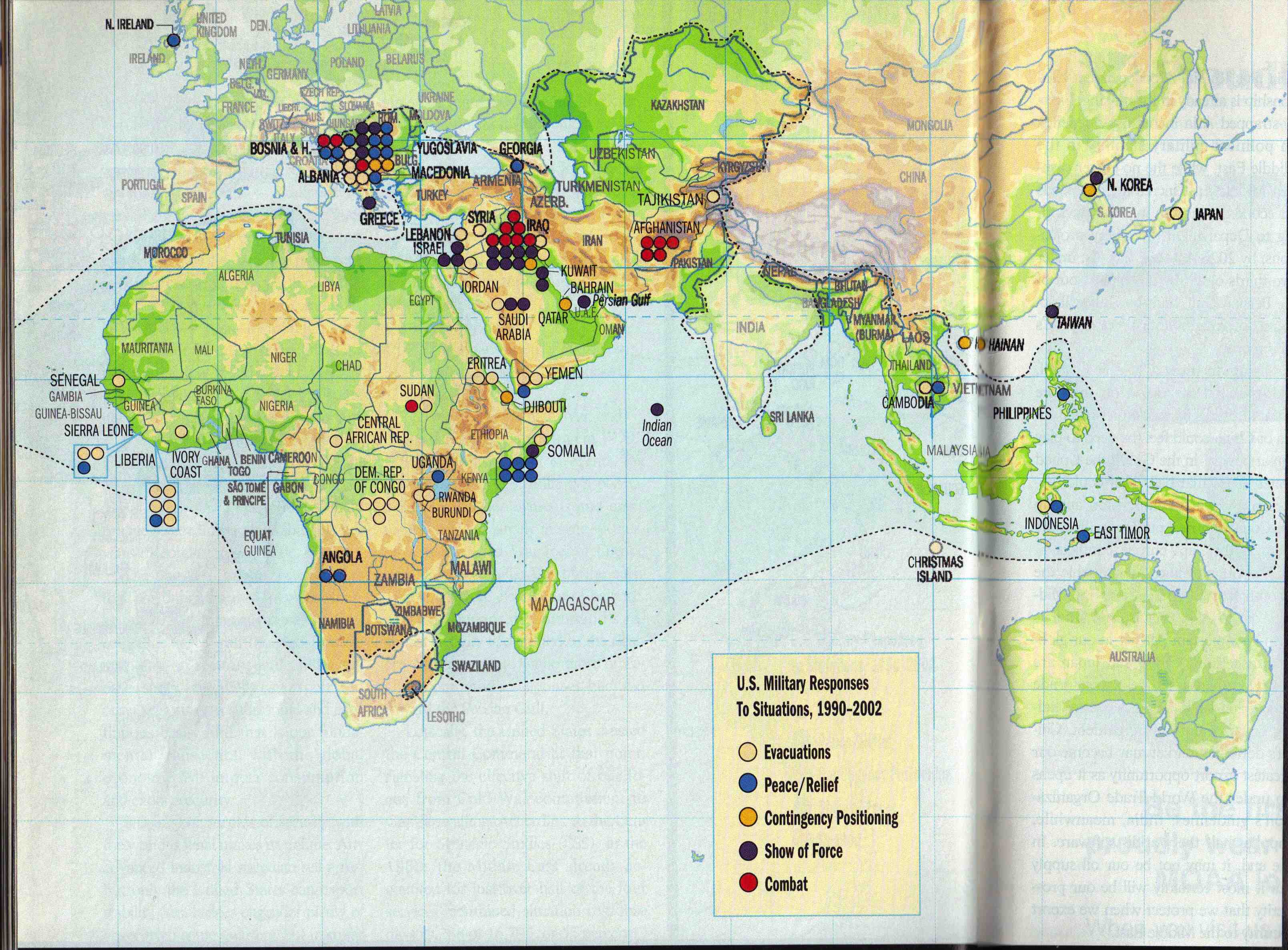

As the head of U.S. Central Command, his beat is the desert that stretches from East Africa to the Chinese border -- a fractious little sandbox with Iraq on one edge and Afghanistan on the other and tens of thousands of American boots already on the ground in both. Pakistan's there in one corner, threatening to boil over and spill its nuclear jihadists forth upon the world; in another, the Gaza Strip continues to hum like a bowstring; and up north, the post-Soviet republics of Central Asia, the 'Stans, rattle along under dictators who range from the merely authoritarian to the genuinely insane. And right in the middle lies Iran.

Where there's peace in the region, how do you keep it? Where there's war, how do you contain it or end it? Where there are threats, how do you counter them? For starters, you might want to make some friends. Which is what Fallon was doing recently on a tour of his area of responsibility.

It's late November in smoggy, car-infested Cairo, and I'm standing in the front lobby of a rather ornate "infantry officers club" on the outskirts of the old town center. Central Command's just finished its large, biannual regional exercise called Bright Star, and today Egypt's army is hosting a "senior leadership seminar" for all the attending generals. It's the barroom scene from Star Wars, with more national uniforms than I can count.

Judging by Fallon's grimace as his official party passes, I can tell that the cover story in this morning's Egyptian Gazette landed hard on somebody's desk at the White House. U.S. RULES OUT STRIKE AGAINST IRAN, read the banner headline, and the accompanying photo showed Fallon in deep consultation with Egyptian president Hosni Mubarak.

Fallon sidles up to me during a morning coffee break. "I'm in hot water again," he says.

"The White House?"

The admiral slowly nods his head.

"They say, 'Why are you even meeting with Mubarak?'" This seems to utterly mystify Fallon.

"Why?" he says, shrugging with palms extending outward. "Because it's my job to deal with this region, and it's all anyone wants to talk about right now. People here hear what I'm saying and understand. I don't want to get them too spun up. Washington interprets this as all aimed at them. Instead, it's aimed at governments and media in this region. I'm not talking about the White House." He points to the ground, getting exercised. "This is my center of gravity. This is my job."

Fallon was quietly opposed to a long-term surge in Iraq, because more of our military assets tied down in Iraq makes it harder to come up with a comprehensive strategy for the Middle East, and he knew how that looked to higher-ups. He also knows that sometimes his statements on Iran strike the same people as running "counter to stated policy." "But look," he says, "yesterday I'm speaking in front of 250 Egyptian businessmen over lunch here in Cairo, and these guys keep holding up newspapers and asking, 'Is this true and can you explain, please?' I need to present the threats and capabilities in the appropriate language. That's one of my duties."

Fallon explains his approach to Iran the same way he explains why he doesn't make Al Qaeda the focus of his regional strategy as Centcom's commander: "What's the best and most effective way to combat Al Qaeda? We tend to make too much or too little a deal about it. I want a more even keel. I come from the school of 'walk softly and carry a big stick.'"

Fallon is the American at the center of every circle in this part of the world. And it is a testament to his skill, and to the failure of American diplomacy, that so much is left for this military man to do himself. He spends very little time at Centcom headquarters in Tampa and is instead constantly "forward," on the move between Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and all the 'Stans of Central Asia.

He was with Pakistani strongman Pervez Musharraf the day before he declared emergency rule last fall. "I'm not the chief diplomat of this country, and certainly not the secretary of state," Fallon says in Kabul's Green Zone the next night. "But I am close to the problems." So, he says, that leaves him no choice but to work these issues, day in and day out.

Late that night, I am sitting with Fallon deep in the compound that encompasses the presidential palace and the International Security Assistance Force. We are alone inside the cramped office of ISAF's chief public-affairs officer.

Fallon had spent several hours with "Mushi" the day before in Islamabad, discussing his impending decision. The press coverage would emphasize how Fallon had sternly warned Musharraf not to impose emergency rule. But on this night, the admiral seems neither alarmed by the move nor resigned to its more negative implications. As he talks, Fallon casually takes off the elastic bands that clamp his camo pants to his regulation tan boots. He's beat after a long day that included meetings with President Karzai and a helicopter trip to Khost, Osama bin Laden's pre-9/11 Afghanistan stronghold. But it was the martial law next door in Pakistan that is the focus of the world. Fallon has been through this before.

"I didn't do any preaching," Fallon says about his talks with Musharraf. "In a previous life here, I had two extra constitutional events: a coup in Thailand, and a head of the military took over in Fiji. So I talked to the president for quite a while yesterday, both with the ambassador and then alone. He walked me through his rationale for what he was going to do and why he was going to do it and why he thought he had to do it. We talked about what planning he'd done for this, the downsides of this, what could happen, and how that could screw up a lot of things. At the end of the day, it's his country and he's the boss of it, and he's going to make his decision."

Before he walked into that room in Islamabad, Fallon had plenty of calls from Washington with instructions to pressure Musharraf down another path.

"I'll talk to him," Fallon replied. "There's an awful lot of china that could break. So I'll do it in a professional manner, because I still have to work with him."

As the admiral recounts the exchange, his voice is flat, his gaze steady. His calculus on this subject is far more complex than anyone else's. He is neither an idealist nor a fantasist. In Pakistan, he has the most volatile combination of forces in the world, yet he is deeply calm. "Did I tell President Musharraf this is not a recommended course of action? Of course. Did I tell him there are very negative effects that this could have? Of course. Is he aware of these? Yes.

"He's made his calculations. He feels very strongly that he's responsible for his country. His alternative is to step down. That would not be the most helpful thing for his country."

Why not?

"It's a very immature democracy. Look at the history of the place. It's rough. Musharraf knows his country. He knows what he's got. Their factions, their tribes. There's that group of folks that wants nothing more than to start war with India, another group that wants to take over the FATA [Federally Administered Tribal Areas], another group that wants to take over part of Baluchistan. He's got a tough road. Most guys in his position do."

As for Washington's notion that Benazir Bhutto's return to the country would fix all that, Fallon is pessimistic. He slowly shakes his head. "Better forget that."

Less than two months later, of course, his rueful prophesy will be confirmed when Bhutto is murdered by militants in Rawalpindi.

Meanwhile, Fallon argues that with U.S. plans in the offing to arm Pashtun tribes against Al Qaeda and the Taliban in the FATA, now would not seem to be the time to be pushing the democracy agenda in Pakistan.

When Fallon asked Musharraf, "How long do you expect to have to do it?" the general answered, "Not long." And twenty-four hours later, Fallon counseled patience. After all, he said, think about how strong America's military relationship is with Egypt despite Hosni Mubarak's twenty-seven-year "emergency rule."

But that doesn't mean the relationship building remains limited to just Musharraf, and so the rest of Fallon's long day in Islamabad was spent networking with General Ashfaq Kayani, former head of Pakistan's much-feared Interservices Intelligence agency and new chief of army staff. If Musharraf were ever to step or be pushed aside, Kayani is a leading contender to replace him.

But more to the point for Fallon, Kayani becomes the operational point man for any increased collaboration between the U.S. military and the Pakistani army to tackle the issues of the FATA, which a Centcom senior intelligence official calls "the huge elephant in the closet."

That's putting it mildly. The tribal region is where, according to our own National Intelligence Estimate last year, Al Qaeda was reconstituting its operational capacity, and was now in its strongest position since 9/11.

As with Pakistan, Fallon keeps his powder dry when he deals with Iran. He doesn't react like Pavlov's dog to inflammatory rhetoric from inflammatory little men. He understands the basic rule of international diplomacy: Everybody gets a move.

"Tehran's feeling pretty cocky right now because they've been able to inflict pain on us in Iraq and Afghanistan." So the trick, in Fallon's mind, is "to try to figure out what it is they really want and then, maybe -- not that we're going to play Santa Claus here or the Good Humor Man -- but the fact is that everyone needs something in this world, and so most countries that are functional and are contributing to the world have found a way to trade off their strengths for other strengths to help them out. These guys are trying to go it alone in this respect, and it's a bad gene pool right now. It's not one with much longevity. So they play that card pretty regularly, and at some point you just kind of run out of games, it seems to me. You've got to play a real card."

And when the real cards finally get played, that's when Fallon will double down.

3.

The first thing you notice is the face, the second is the voice.

A tall, wiry man with thinning white hair, Fallon comes off like a loner even when he's standing in a crowd.

Despite having an easy smile that he regularly pulls out for his many daily exercises in relationship building, Fallon's consistent game face is a slightly pissed-off glare. It's his default expression. Don't fuck with me, it says. A tough Catholic boy from New Jersey, his favorite compliment is "badass." Fallon's got a fearsome reputation, although no one I ever talk to in the business can quite pin down why. There are the stories of his wilder days as a young officer, not the partying stuff but more the variety of rules bent to the breaking point, and he's been known as anything but a dove in his various commands, which makes his later roles as champion for engagement with both China and Iran all the more strange.

In keeping with the naval-officer tradition of emasculating bluntness, Fallon can without remorse cut the nuts off peers and subordinates alike. But it is more the intimation of his ferocity than its exercise that has the greatest effect. And Fallon has recently discovered that his reputation can leave him open to stories that might sound true but are not. Last fall, it was reported in the press that Fallon had called General Petraeus an "ass-kissing little chickenshit" for being so willing to serve as the administration's political frontman on the Iraq surge. The old man had told reporters that it hadn't happened like that -- that that's not the way he operates, and, in fact, any time he talks with Petraeus, there are only two men in the room -- the admiral and the general -- and their exchanges remain private. And when they're not in the same room, "We e-mail each other constantly and talk by phone just about every day." Just the two of them, he says. No outsiders observing. The press sources had an overactive imagination, Fallon said. Now when the subject comes up, he dismisses it with a wave of his hand.

"Absolute bullshit," Fallon tells me.

Fallon and his executive assistant, Captain Craig Faller, say that they both suspect "staff agitation" to be behind the story. Interservice rivalry is mighty strong, and Admiral Fallon is the first navy man to be head of Centcom, so it's not hard for them to imagine somebody from the Army stirring the pot.

Fallon says the tip-off that the story was bogus was the word chickenshit. "My kids called me up laughing about that one, saying they knew the story wasn't true because I never use that word."

So put Fallon down as a "bullshit" and not a "chickenshit" kind of guy.

And in truth, Fallon's not a screamer. Indeed, by my long observation and the accounts of a dozen people, he doesn't raise his voice whatsoever, except when he laughs. Instead, the more serious he becomes, the quieter he gets, and his whispers sound positively menacing. Other guys can jaw-jaw all they want about the need for war-war with...whomever is today's target among D.C.'s many armchair warriors. Not Fallon. Let the president pop off. Fallon won't. No bravado here, nor sound-bite-sized threats, but rather a calm, leathery presence. Fallon is comfortable risking peace because he's comfortable waging war. And when he conveys messages to the enemies of the United States, he does it not in the provocative cowboy style that has prevailed in Washington so far this century, but with the opposite -- a studied quiet that makes it seem as if he is trying to bend them to his will with nothing but the sound of his voice.

So when, during a press conference in Astana, Kazakhstan, Fallon whispers, "The public behavior of Iran has been unhelpful to the region," with his pissed-off glare and his slightly hoarse delivery, he is saying, I'm not making you an offer; I'm telling you what your options are right now.

"Iran should be playing a constructive role," he continues. "I hear this from every country in the region."

Translation: I've got you surrounded.

He'd rather not do it, but if he has to go to war, there won't be any anguish. Whatever qualms Fallon had about using force were exorcised long ago in the skies over Vietnam.

"I try to be reasonably predictable to my own people and very unpredictable to potential adversaries," he tells me.

No wonder Fallon sticks out like a sore thumb with the neocons, who have the unfortunate tendency to come off as unpredictable to their allies and predictable to their enemies. Which is the opposite of strategy. He knows this stuff cold, because he's had his hand on the stick for a very long time. The oldest of nine kids, Fallon's old man was a mailman in Merchantville, New Jersey, following his World War II stint in the Army Air Corps. As a boy, Fallon delivered newspapers, bagged groceries, worked in the local Campbell's Soup plant, and would become the first in his family to attend college. His dad's military experiences, along with those of several of his mom's brothers, naturally pushed him in the direction of West Point.

But his local congressman screwed up his application, and so Fallon chose the naval ROTC program at nearby Villanova, a Catholic haven that has produced three Centcom commanders. More than thirteen hundred carrier landings later, Fallon began his long climb through various combat command experiences -- including Desert Storm and Bosnia -- to the pinnacle of his profession: four four-star assignments that include vice chief of Naval Operations, commander of the Atlantic Fleet, and then boss of Pacific Command and Central Command in rapid succession.

Sitting in his Tampa headquarters office last fall, I asked Fallon if he considered the Centcom assignment to be the same career-capping job that it'd been for his predecessors. He just laughed and said, "Career capping? How about career detonating?"

At the time, I took that comment to be mere self-effacement. I have since come to think that Fallon was deadly serious.

Weeks later, back in that hotel lounge in Kazakhstan, after a brutal eighteen-hour day of wall-to-wall summits and meetings, Fallon is in a more pensive mood, admitting that he never expected to stay this long in the service. At sixty-three, he's one of the oldest flag officers in uniform, and if you count his ROTC time, he's been in for a whopping forty-five years total. And at this cookie-cutter chain hotel deep in the 'Stans, Fallon wears an expression that is equal parts fatigue and bewilderment. "I expected to be running a start-up company by now," he says.

But something else came up.

4.

When the admiral took charge of Pacific Command in 2005, he immediately set about a military-to-military outreach to the Chinese armed forces, something that had plenty of people freaking out at the Pentagon and on Capitol Hill. The Chinese, after all, were scheduled to be our next war. What the hell was Fallon doing?

Contrary to some reports, though, Fallon says he initially had no trouble with then-secretary of defense Donald Rumsfeld on the subject. "Early on, I talked to him. I said, Here's what I think. And I talked to the president, too."

It was only after the Pentagon and Congress started realizing that their favorite "programs of record" (i.e., weapons systems and major vehicle platforms) were threatened by such talks that the shit hit the fan. "I blew my stack," Fallon says. "I told Rumsfeld, Just look at this shit. I go up to the Hill and I get three or four guys grabbing me and jerking me out of the aisle, all because somebody came up and told them that the sky was going to cave in."

But Fallon stood down the China hawks, because as much as military leaders have to plan for war, Fallon seems to understand better than most the role they also have to play in everything else beyond war. And like a good cop, Fallon doesn't want to fire his gun unless he absolutely has to. "I wouldn't have done what I did if I didn't think it was the right thing to do, which I still do. China is our most important relationship for the future, given the realities of people, economics, and location. We've got to work hard and make sure we do our best to get it right."

For Fallon, that meant an emphasis on opening new lines of communication and reducing the capacity for misunderstanding during times of crisis. But beyond that, it meant telling the Chinese, "If you want to be treated as a big boy and a major player, you've got to act like it."

If you want recognition of your power, then you have to accept the responsibility that comes with such power. That's the essential message Fallon delivered to the Chinese, and if that meant he was out of line with the Pentagon's take on rising China, then so be it. If it seemed as though Fallon was downplaying the threat of North Korea's missiles, it was because he preferred pushing a regional response that signaled a united front but still left the door open for North Korea to come in from the cold.

Fallon now brings the same approach to Iran in Central Command: "I want to go through something positive rather than a negative like Iran, which is a real problem." To that end, and right on the heels of Secretary of Defense Robert Gates's meetings with Middle Eastern ministers of defense, Fallon held a similar summit of Persian Gulf chiefs of defense in Tampa earlier this year, something Centcom has never attempted before.

Could Iran be a participant in something like this down the road?

"Oh, absolutely, eventually. It's like the Chinese," he says. "It would be great if Iran turned into a team that decided to play ball in the end."

So how does something like this happen?

How do you turn Iran into a responsible regional player? How can the United States even approach Iran when the regime seems populated by only hard-liners and ultraconservatives?

You start down low, says one of Fallon's senior intelligence officials. For example, there's the shared interest in stemming the flow of narcotics from Afghanistan to Iran. "Iran has a huge drug problem," so that's "a potential cooperative area." More recently, the Iranians promised to stop the flow of munitions into Iraq, arguably contributing to the dramatic decrease in U. S. casualties from roadside bombs. After three sets of talks with the Iranians last summer that went nowhere, another round is being teed up. To Fallon, this sort of engagement is crucial, given America's overall lack of experience in dealing with Iran.

"I don't know as much as I'd like about Iran," he says. "You've got to go elsewhere, to people in other countries. There aren't many Americans who've had extensive experience with these guys. So that puts us both at a disadvantage. Plus they're secretive -- intentionally so -- about us. It makes it more of a challenge."

Early in his tenure at Pacific Command, Fallon let it be known that he was interested in visiting the city of Harbin in the highly controlled and isolated Heilongjiang Military District on China's northern border with Russia. The Chinese were flabbergasted at the request, but when Fallon's command plane took off one afternoon from Mongolia, heading for Harbin without permission, Beijing relented.

The local Chinese commander was beside himself. It was the first time in his life he had ever met an American military officer, and here he was at the bottom of a jet ramp waiting for the all-powerful head of the United States Pacific Command to descend. Then, to his horror, he realized that Fallon had brought his wife, Mary, along for the trip. Scrambling to arrange the evening banquet, the Chinese commander brought his own wife out in public for the first time ever.

When the time came for dinner toasts, after the Chinese commander thanked Mrs. Fallon for coming, the admiral returned the favor by thanking the commander's wife for her many years of service as a military spouse. The commander's wife broke down in tears, saying it was the first time in her entire marriage that she had been publicly recognized for her many sacrifices.

And there was peace in our time.

5.

Fallon is what is called a "four-star action officer," meaning he tries to do too many things himself. He spends no more than a week each month in Tampa, Centcom's headquarters. Captain Faller jokes that if it weren't for federal holidays, Fallon's staff wouldn't know what a day off even was.

Fallon travels at least three weeks out of each month, spending, on average, two weeks in theater, meaning the Middle East, the Horn of Africa, and Central Asia. He travels to Iraq and Afghanistan every month like clockwork.

It's an unseasonably warm early-winter morning in Kabul, and Fallon is out in the field, walking his beat. And short of the president of the United States himself, this convoy is the richest and most opportune terrorist target in the world at present. So everybody wears the heavy armor. Weighed down by a helmet that feels like twenty pounds -- applied directly to my forehead -- and a desert-camo flak jacket that's decidedly heavier, I climb into the back of an armored Suburban that'll play third-on-a-match in Fallon's three-vehicle convoy. We are told to expect a bumpy ride, as ours is the vehicle that will routinely swerve from side to side to position itself to ram any vehicle that might approach the command vehicle from the side.

It's like riding in a car with the biggest asshole in the world behind the wheel. We almost pass Fallon's vehicle -- time after time -- only to slam on the brakes, slip back behind, lurch over to the other side, and do the same thing. A word of advice: Don't do this on a heavy breakfast. Fallon's personal enlisted aide, strapped in next to us, says our driver is actually being fairly mellow, on the admiral's orders. That's good to hear, as the streets are full of women and children on foot.

Thirty minutes after we've left the maze of barricades that line every entrance into the Green Zone, giving the place a sort of Maxwell Smart sense of never-ending doors, we arrive at a military airport where two Black Hawk UH-60's await. I ride with Fallon's senior aides in the second one. I am strapped into a four-part harness, the body armor keeping me well cocooned. Minutes after takeoff, as is the universal custom among military personnel, everyone but the personal-security-detail soldiers is asleep.

I scan the moonscape that is the mountains west of Kabul.

Traveling at high speed, we've been dipping ever so gently around the mountains as we travel to Bamiyan Province, ancient home to the giant Buddhas that are no more -- parting shots from the once and future Taliban. I can spot Fallon's Black Hawk out the window, framed from above by the sky and below by the barrel of a large machine gun sticking out of our helicopter's side. It's manned by a rather short fellow whose face is almost completely obscured by his Star Wars blast shield.

The view is amazing and reminds me why banditry and smuggling remain dominant industries here. Every road seems to lie at the bottom of a narrow, meandering ravine, and every walled compound looks like a fort out of America's Wild West days. Most of the time, the only things moving across this barren landscape are the shadows from our helos.

We alight from the Black Hawks after touching down on a strip of asphalt located in the center of the wide, flat plain that is Bamiyan Valley. Immediately your eyes are drawn to the dominant geological feature: cliff walls as high as skyscrapers that run along the valley's northern edge as far as the eye can see. Carved into the stunning vertical cliff are two empty frames, each running fifteen or so meters deep into the rock. Here stood the gigantic stone Buddhas carved hundreds of years ago by monks who lived in a warren of caves connecting the statues.

We're met at the landing zone by the Kiwi colonel, Brendon Fraher, who leads a small unit of New Zealand's finest civil-affairs specialists operating out of a small fort a few clicks away. The camp is home to a Provincial Reconstruction Team manned by the Kiwis, who work hand in glove with U.S. State Department, U.S. Agency for International Development, and ISAF personnel in coordinating coalition reconstruction aid to this province.

As we head to a convoy of armored Ford F-350 pickups, Fallon says that Fraher reports two enemy rockets landed nearby yesterday, but other than that, all's quiet. We speed off to meet the only female provincial governor in Afghanistan. Pulling up to the local government building, we pile out of the pickups and file into a large receiving room blanketed by modest Persian rugs and surrounded by even more modest couches. Just inside, we strip off the helmets and vests and heap them into a pile of fabric-covered metal and ceramic in the corner, all of it too heavy to hang on any coatrack.

Fallon -- who's done this sort of thing so often, he seems to glide through the protocol -- zeroes in on Governor Habiba Sarabi, a middle-aged woman of average height who's dressed in a reform sort of way -- head covered but face exposed. Despite all our accompanying security, you've got to believe she's the biggest Taliban target in the room.

Tea is served and formal greetings are exchanged with no need for translation, as the governor speaks English with calculated fluency, a skill she demonstrates a half hour into the meeting, when Fallon makes clear that he wants to hear her complaints.

It's a tricky moment for Sarabi, because she's basically critiquing Western aid and the military agencies represented by the officials surrounding her now. It's like bitching about your parents in front of Child Protective Services: Strike the right note and you might suddenly find yourself free of them for good.

Speaking about a road long-promised by Kabul and the coalition that would connect this isolated valley to Afghanistan's central circular artery, the Ring Road, she suddenly blurts out, "This is three years that the Bamiyan people have been waiting for this road!"

Fallon aggressively queries the assembled officials in order, running from the deputy chief of mission at the U.S. embassy to the USAID leader to the ISAF officers and, finally, the local Kiwi PRT commander. Each offers a typically complex, bureaucratic response in turn. Glancing at the governor, I can almost feel her anger rising.

With obvious passion, Sarabi interrupts the proceedings with a stream of complaints about the length and complexity of USAID's planning process. This is where her fluency in English suddenly falters, as Sarabi's sentences start trailing off, leading the assembled officials to fill in the blanks.

"It is very... "

"Long?" chimes in the USAID official.

"And there is such a lack of...ahh." Sarabi raises a finger to her chin, scanning the far wall as if the word lingers there.

"Coordination?" offers the deputy chief of mission.

"It all makes me so incredibly...how do you say?"

"Mad?" one officer suggests.

"Depressed?"

"Angry?"

It's almost like an auction now as the bids keep rising. I'm just about ready to toss in my personal favorite, "pissed off," when Fallon weighs in with "frustrated" -- no question mark.

Sarabi turns toward the admiral, a sly smile passes across her face.

Fallon starts probing yet again, this time cutting off officials, as their answers obscure rather than illuminate.

Emboldened, the governor piles on with a new complaint: Every winter, a local river becomes impassable for a local migratory tribe that is then stranded outside the valley.

Fallon asks the deputy chief of mission, "Are you aware of this?"

The DCM replies, "No, I wasn't, and I promise to look into that."

Fallon's on a roll now, and the governor is beaming, but his efforts soon head into a bureaucratic cul-de-sac that no one in the room can fix. Kabul's central government simply does not prioritize this heartland province. Fallon asks the senior American ISAF officer if the coalition could arrange a Bailey pontoon bridge just for the winter months. In return, he gets a complex answer about past surveys.

Fallon cuts him off and turns to the governor. "I tell you what, I'm not getting a satisfactory answer here. I'll be honest. I don't think we can do anything for you this winter. However, I will try to get, from many miles away, a screwdriver big enough to push this process for next year."

The governor immediately thanks Fallon for his promise.

Fallon doesn't forget details like that. Six months earlier, he noticed that the American flag flying outside the Hyatt hotel in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan, was frayed. He had told one of the defense attachés at the U.S. embassy to get it replaced. The beaten-up flag was still there when we arrived. It's late on the fifth straight day of nonstop travel that has taken Fallon's entourage from Florida to Qatar to Pakistan to Afghanistan and now to Kyrgyzstan. Tomorrow, Tajikistan, where he'll have to put up with the Putin clone who is president. So at the moment, maybe the flag is not all that's frayed. His gaze fixed on it, Fallon quietly repeats his order, his voice so low and so quiet that you can almost hear somebody's next promotion getting axed.

6.

Unlike his Arabic-speaking predecessor, Army General John Abizaid, Fox Fallon wasn't selected to lead U.S. Central Command for his regional knowledge or cultural sensitivity, but because he is, says Secretary of Defense Gates, "one of the best strategic thinkers in uniform today."

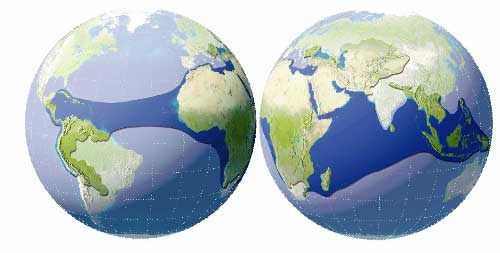

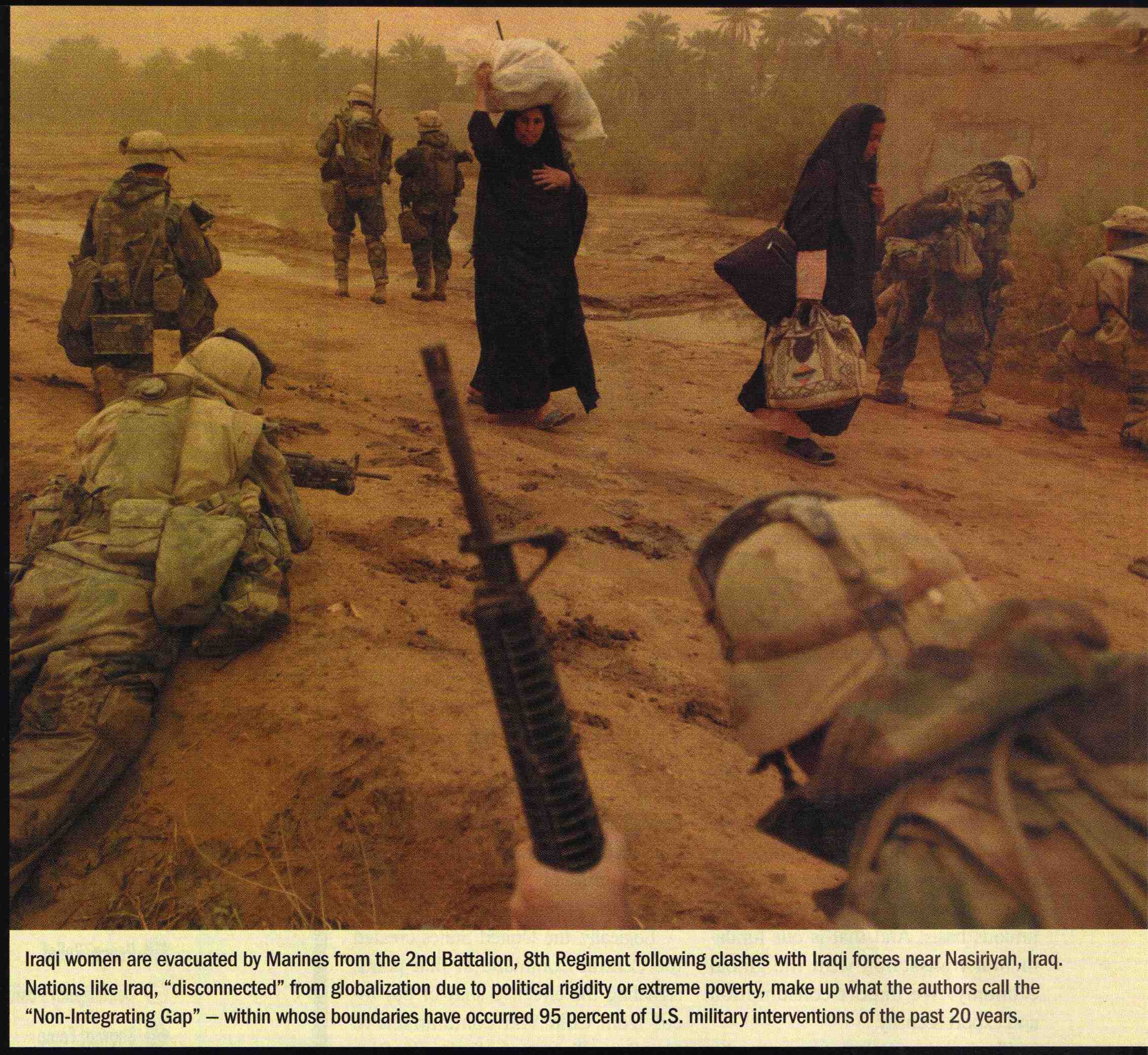

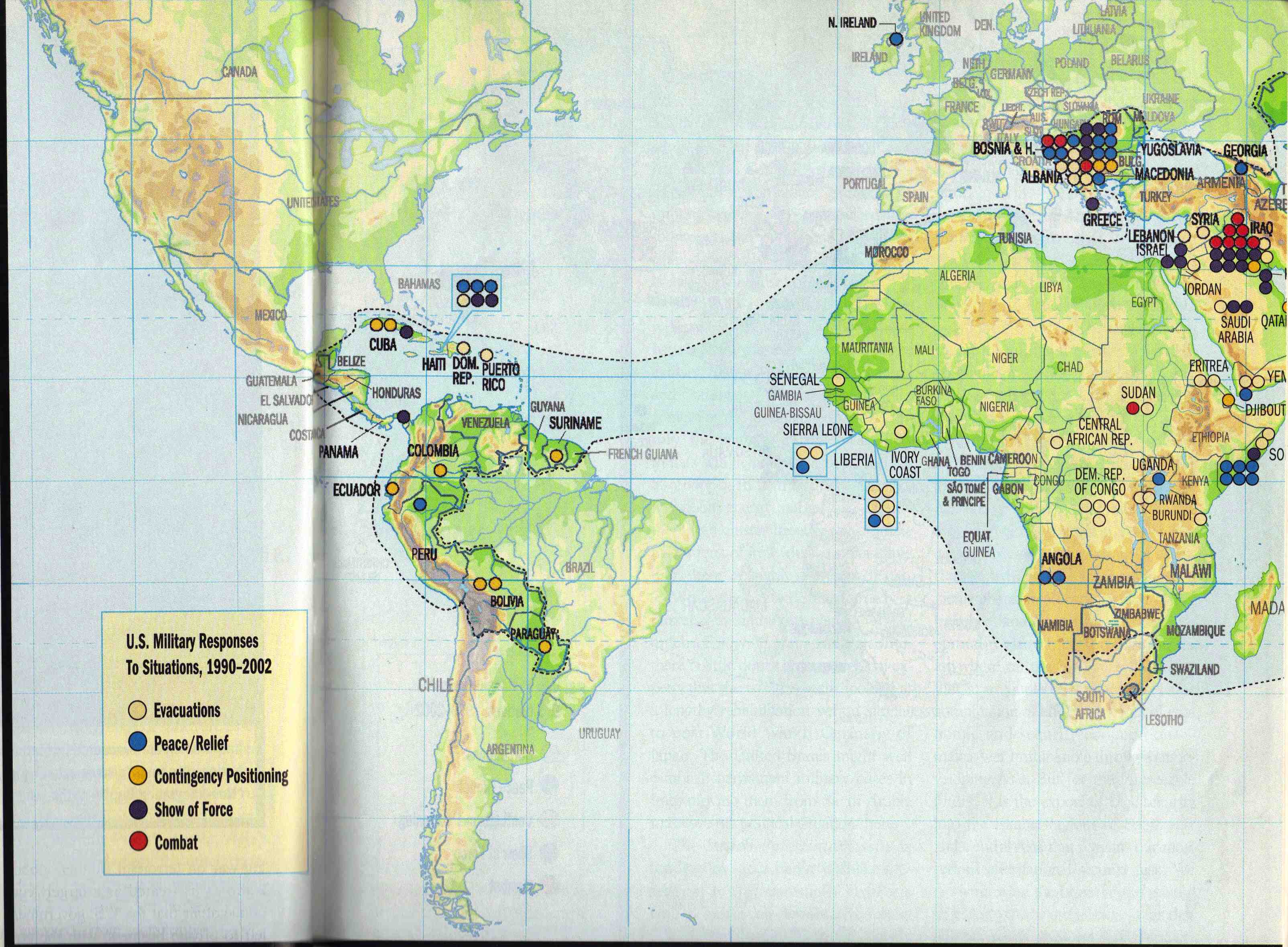

If anything has been sorely missing to date in America's choices in the Middle East and Central Asia, it has been a strategic mind-set that consistently keeps its eyes on the real prize: connecting these isolated regions in a far more broadband fashion to the global economy. Instead of effectively countering the efforts of others (e.g., the radical Salafis, Saudi Arabia's Wahhabists, Russia's security services, China's energy sector) who would fashion such connectivity to their selfish ends, Washington has wasted precious time focusing excessively on transforming the political systems of Iraq and Afghanistan, as though governments somehow birth functioning societies and economies instead of the other way around.

Waiting on perfect security or perfect politics to forge economic relationships is a fool's errand. By the time those fantastic conditions are met in this dangerous, unstable part of the world, somebody less idealistic will be running the place -- the Russians, Chinese, Pakistanis, Indians, Turks, Iranians, Saudis. That's why Fallon has been aggressively hawking his southern strategy of encouraging a north-south "energy corridor" between the Central Asian republics and the energy-starved-but-booming Asian subcontinent (read: Islamabad down through Bangalore and then east to Kolkata), with both Afghanistan and Pakistan as crucial conduits.

On this trip, he's been shepherding a new bridge that links isolated Tajikistan with Afghanistan. The potential here is huge: Tajikistan is 95 percent mountainous and extremely food dependent. Its main asset is its untapped hydroelectric capacity. Afghanistan presents just the opposite picture -- food to export but most of the country lacks an effective electric grid.

So what should America be pushing first in both states? Free-and-clear elections for massively impoverished populations, or whatever it takes to get Tajikistan's resource with Afghanistan's resource? Which path, do you think, would scare the Taliban and Al Qaeda more? To Fallon, there isn't even a question to answer.

But this part of the world is defined by its fortresses, and is not known for willingly connecting to the outside world. Tajikistan's powerful security chief, Khayriddin Abdurahimov, had been doing his best to gum up the works on the just-finished bridge, which he allowed to open for business only four hours a day. Having just achieved control of the country's border-security agency, Abdurahimov believed the bridge made the country vulnerable to Afghanistan's dangerous drugs and nothing more.

On the eve of Fallon's arrival, President Emomali Rahmon intervened and extended the bridge's operating schedule to eight hours a day, admitting to Fallon in their first summit that he needs to do more to champion the economic potential.

But Fallon doesn't stop there. Immediately following his meeting with Rahmon, he meets face-to-face with the highly secretive Abdurahimov, who almost never meets with foreign officials.

Just as with Musharraf, Fallon does not preach. He suggests, he encourages, he cajoles, he offers, and he debates, but he does not preach -- save the gospel of economic connectivity. Even there, he is not eager to appear competitive with any regional power. "I don't want to create the impression that we're just replacing the Russians," he says.

He just wants a damn bridge.

Fallon gets his bridge.

7.

Fallon's got a spread in a little town in Montana. The streams of this town seem to be full of eighteen-inch fish that he says he'd like to take a crack at someday soon. But the fish of Fallon's town are safe for the moment.

While Condoleezza Rice and the State Department manage a vague endgame on the two-state solution in Palestine, Gates and Fallon have begun the regional-security dialogue that's truly regional in scope.

The rollback of Al Qaeda seems to be both real and continuing, save for the border region of Pakistan. And to gain greater flexibility to plan for the region, Fallon says that he is determined to draw down in Iraq. One of the reasons Fallon says he banished the term "long war" from Centcom's vocabulary is that he believes real victory in this struggle will be defined in economic terms first, and so the emphasis on war struck him as "too narrow." But the term also signaled a long haul that Fallon simply finds unacceptable. He wants troop levels in Iraq down now, and he wants the Afghan National Army running the show throughout most of Afghanistan by the end of this year. Fallon says he wants to move the pile dramatically in the time he's got remaining, however long that may be. And he gets frustrated. "I grind my teeth at the pace of change."

Freeing the United States from being tied down in Iraq means a stronger effort in Afghanistan, more focus on Pakistan, and more time spent creating networks of relationships in Central Asia. With Syria and Lebanon recently added to Centcom's area of responsibility, look to see Fallon popping up in Beirut and Damascus regularly. And he says he is more than willing to take on Israel and Palestine to boot, which for now remains a bastard stepchild of European Command.

The Persian Gulf right now is booming economically, and Fallon wants to harness that power to connect the failed states that pockmark the landscape to the outside world. In this choice, he sees no alternative.

"What I learned in the Pacific is that after a while the tableau of failed, failing, or dysfunctional states becomes a real burden on the functional countries and a problem for their neighborhood, because they breed unrest and insecurities and attract troublemakers very well. They're like sewers, and they begin to fester. It's bad for business. And when it's bad for business, people tend to start restricting their investments, and they restrict their thinking, and it allows more barriers, so we're back to building walls again instead of breaking them down. If you have to build walls, it means you're moving backward."

Fallon has no illusion about solving the Middle East or Central Asia during his tenure, but he's also acutely conscious that with globalization's rapid advance into these regions he may well be the last Centcom commander of his kind. Already Fallon sees the inevitability and utility of having a Chinese military partnership at Centcom, and he'd like to manage that inevitably from the start rather than have to repair damage down the line.

"I'd like to continue to do things that will be useful to the world and its inhabitants," he says. "I've seen a lot of good things, and I've seen a lot of stupid things."

And then there is Iran. No sooner had the supreme leader Ayatollah Khamenei signaled a willingness to deal with any American but George W. Bush, and no sooner had Fallon signaled America's willingness to refrain from bombing Tehran, than a little international incident occurred.

Just the kind of incident that doughy neocons dream sweetly about. Right after the new year, three American ships were passing through the Strait of Hormuz, exchanging normal greetings with Gulf State navies, checking them out as they passed. The same with the Iranian navy. And then, suddenly, small Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps boats started speeding toward the American ships, showing, the admiral says, "very stupid behavior, showboating, and provocative taunts. Given that it was a small boat that did in the USS Cole, this was very dangerous behavior."

The Iranians dropped boxes in the water, simulating mines.

"Remember," he says, "my first day on this job, I was greeted by the IRGC snatching the British sailors, and so it was a sense of here we go again. You wonder, Are they really acting on their own, because the pattern seems clear."

Fallon's eyes narrow and his voice becomes that whisper: "This is not how a country that wants to be a big boy in the neighborhood behaves. How are we supposed to take these guys seriously as players in the region? You'd like to deal with them as big-league players, but when they do this, it's very tough."

As before, there is the text and the subtext. Admiral William Fallon shakes his head slowly, and his eyes say, These guys have no idea how much worse it could get for them. I am the reasonable one.

And time will tell whether being reasonable will cost Admiral William Fallon his command.

Tuesday, August 31, 2010 at 12:02AM

Tuesday, August 31, 2010 at 12:02AM  Sean Lawson writing at his ICTs and International Relations blog.

Sean Lawson writing at his ICTs and International Relations blog.