The big challenge for the field of organizational resilience is its uncomfortably close association with national/international security thinking (from which I hail in training and the bulk of the career experiences). As a rule, national-security types want you to be afraid - very afraid!Why? The professional in me says that's just them doing their job in a "dangerous world." The cynic in me says that's their version of marketing, which is often the sad equivalent of fear-mongering – as in, the more afraid you are, the more important they become. I mean, ask yourself: when you watch TV and see experts opining on some crisis/conflict, do you ever hear them say that the situation is getting better? No, you don't. In this business, everything is always getting increasingly something (dangerous, worse, violent, unstable, uncertain, uncontrollable – pretty much un-anything).

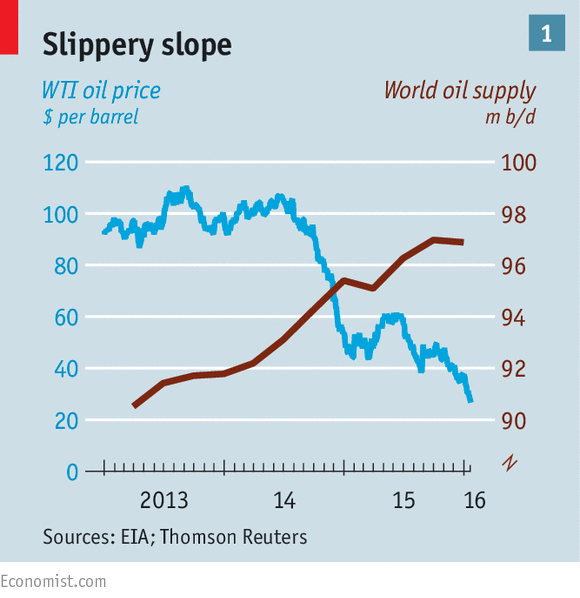

History, of course, says otherwise. In my lifetime, which began on the eve of the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962, we've seen wars growing less frequent, shorter, and less lethal. And not by a little bit, mind you, but by a lot. I could throw a ton of stats and sites at you, but the chart above demonstrates the history awfully well. Mind you, that's battle deaths per 100,000 people. With numbers that just go up through 2013 (of course, they're increasing since then!), we see that the battle death rate, while rising from the early-2000s supreme low of less-than-one-person(!)-per-100,000 to the "disturbing" almost-one-person(!!)-per-100,000, is still lower than virtually all of history since WWII (only the "chaotic" year of 1996 – sarcasm mine – compares, and that was the most peaceful year since 1954, or before decolonialization began).

What else the chart tells us:

- The "unprecedented" disasters of the Iraq and Afghanistan wars were . . . to be frank, minor compared to the 1990s, which we all collectively remember as being an awfully quiet decade outside of a handful of conflicts/disasters (Bosnia, Iraq, Somalia, Haiti, central Africa).

- The 1990s themselves were far more quiet than the 1980s, which seemed bad only in comparison to the quiet shadow created by the Indochina wars of the 1960s and 1970s.

- Those 1960s/early 70s Southeast Asian wars were bad compared to the quiet 1950s (when we only feared total nuclear annihilation – sigh!).

- But Vietnam etc. was quite a come-down from the scary and destabilized post-WWII/Korean War segment.

What you don't see on the chart: World War II stretching over roughly a decade and killing - on average - 15,000 people a day for well over 3,500 days. That, my friends, was a world war.

So, imagine my surprise as an expert on conflict/international relations/global trends to see WAPO this morning declare the battle for a single city in Syria to constitute a "mini world war."

Why mini? Well, I'm guessing that a death rate of 150/day (my best estimate using a lot of other estimates) is a big part of it. That's actually quite high for a war nowadays, because most experts will label any conflict with an average of 3 deaths/per day (1,000+ for year) to be a "war." But when your last true world war yielded a death rate 100-times higher, even "mini" seems like a wild exaggeration.

No, the reason why WAPO embraces this sort of reckless hyperbole is because Russia is now in the mix, sending Cold War-like chills down our collective spines. Naturally, this raises old fears of "escalation" – presumably to global nuclear war.

Except neither side is talking that, or acting that, or anything-ing that.

Instead, the great "evidence" cited in the piece (besides some self-serving observations by a security contractor working the conflict) is Russian Premier Dmitry Medvedev dropping hints in Europe this week about a new, Cold War-like dynamic between Russia and the West.

The great cause there? Obviously, Russia's land grab of the Crimea and the easter portion of Ukraine (the former formally, the latter informally). That led to the West placing a lot of economic sanctions on a Russian economy already faltering and now nosediving in terms of its number-one export – energy, thanks to historically low global prices.

So, what does Russia seek with its military intervention in Syria? To prove it's a "dominant" Middle Eastern power, as the story's author opines? Well, a relevant power is a less screechy expression.

But try this alternative explanation on for size: Russia is hurting from the sanctions and needs to come in from the economic "cold" imposed on it by the West over Ukraine. But how to do it? Why not intervene in a place of high global interest, one which the U.S. is lowballing in terms of effort? All of a sudden, look how important Moscow is to the "peace process"! And if Moscow is seen as holding enough of the cards on the Assad regime, maybe asking for its help there will be matched by the West forgetting its transgressions in Ukraine.

Sound like a "mini world war" to you? Or just the cantina scene from the original Star Wars movie?

Syria is a civil war. Civil wars today tend to get internationalized (all those characters in various uniforms in the cantina ...). We lament that development, but, let me remind you what we used to call states where conflicts raged and nobody from the outside showed up. Those we called "failed states" back in the 1990s. We still have a few now (same 1-2 dozen out of roughly 200 states in the world). But, if, by and large, few outsiders show up, those conflicts that have "failed" to attract any serious global attention are simply forgotten. So maybe we should call them "forgotten states."

Syria is not a forgotten state. A lot of regional and a few extra-regional powers are interested. Are they interested enough to stop the conflict? Not really. Are they interested enough to stop the conflict from going against their side? Just barely.

But should we look at that and invoke the imagery of a world war?

That is just shameful fear-mongering on the part of WAPO trying to sell your eyeballs to their advertisers. The paper is simply repurposing Medvedev's propaganda as deep insight: he peddles "new Cold War" to amp up the West's sense of danger, hopefully (from Moscow's perspective) rendering the Obama Administration more amenable to compromise on Ukraine. WAPO knee-jerkedly transmutes that bit of diplomatic salesmanship into a "mini world war" on Aleppo. (You say Sarajevo, I say Aleppo, oh let's call this world war off!)

Scared? You're supposed to be. The Syrian Civil War is a genuine human tragedy, but re-packaging it as a "mini world war" is just inaccurate-bordering-on-journalistically-negligent.

Is this picking on WAPO? Absolutely, but only because I respect the paper so much and constantly cite it here in this blog. Frankly, its editorial staff should know better.

Again, the larger point here is maintaining perspective, because, when we lose it, we become brittle as individuals, decision-makers, leaders, and nations. Brittle, scared actors make bad choices; they do stupid things. They lash out because they imagine it to be the only option left, after issuing over-the-top threats . . . typically in response to hyperbolic media coverage (see debates in US presidential race for way too many examples).

So no, it's not all the fault of the media, although they start the process. They just give us what we want, which is fear. Nowadays we seem to collectively crave fear of complexity and chaos and uncertainty – the holy trinity of fear-mongers everywhere.

But do yourself a favor and don't buy any of it, because fear is the mind-killer - the little death, and the ultimate enemy of resilience.

Monday, September 9, 2019 at 9:15AM

Monday, September 9, 2019 at 9:15AM