The "last battlefield" dynamic in Long War finally comes into focus (for those paying attention)

Saturday, February 22, 2020 at 8:57PM

Saturday, February 22, 2020 at 8:57PM

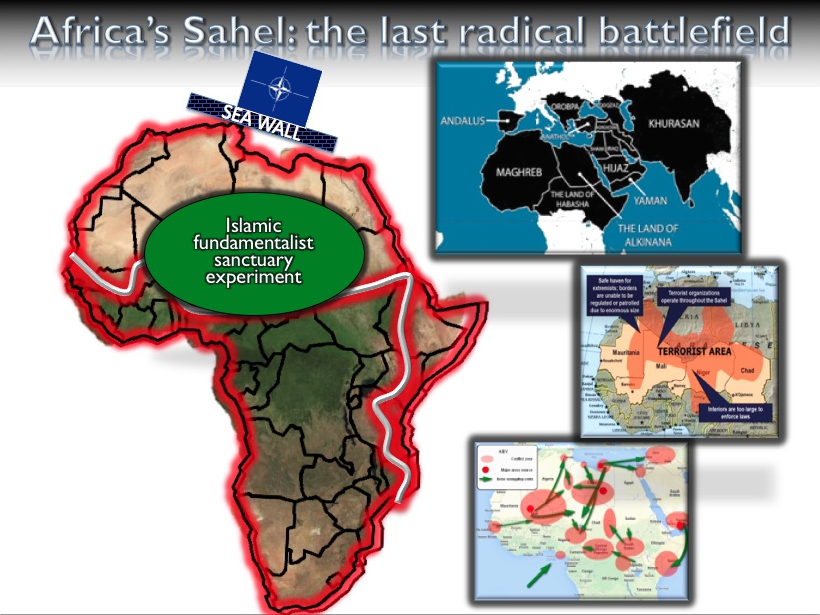

The above slide is from my state-of-the-world brief of the last decade: The basic argument being: Trump will outsource U.S. foreign policy in the Middle East to the Saudis, Emiratis, Israelis, and Russians (all of whom played major meddling roles in our 2016 election [and own our POTUS in various financial ways] and are doing the same this time around), leaving the Europeans to handle North Africa on their own. The US-less NATO thus tries a "sea wall" strategy to keep bad things from coming across the Med, but essentially takes a strategy of limited regret regarding the continent, which corresponds to Trump pulling U.S. troops from the continent (well underway). With radical Islam largely crushed in PG and no great escape possible to Central Asia (too many regional powers RWA to do a "Chechnya" on any situations [as Putin did to both Chechnya and now Syria]), then the path of least resistance for the AQs and Islamic States of radical Islam is to come together at create the new caliphate(s)/radical Islamic sanctuary in the Trans Sahel - the least governed territory in the world.

Going back further to a Battleland blog post I wrote in 2011 ("An Explosive Glimpse of the Future of the Long War in Africa"):

As the radical Islamic pulse continues to fail/peter out in the Middle East and North Africa, this is where it comes next.

Why? Globalization is penetrating Africa big-time, mostly driven by ravenous Chinese resource demands, and the socio-economic churn creates potential conflicts that radical Islamists will seek to exploit. So yeah, AFRICOM becomes more important over time.

Finally, from the pre-AFRICOM Blueprint for Action: A Future Worth Creating (2005), which, BTW, predicted the establishment of an Africa Command in its final chapter):

CENTCOM’s AOR encompasses the Persian Gulf area extending from Israel all the way to Pakistan, the Central Asian republics formerly associated with the Soviet Union, and the horn of Africa (from Egypt down to Somalia). This is clearly the center of the universe as far as the global war on terrorism is concerned, and yet viewing that war solely in the context of that region alone is a big mistake, one that could easily foul up America’s larger grand strategic goals of defeating terrorism worldwide and making globalization truly global. Here’s why: CENTCOM’s area of responsibility features three key seams, or boundaries, between that collection of regions and the world outside. Each seam speaks to both opportunities and dangers that lie ahead, as well as to how crucial it is that Central Command’s version of the war on terrorism stays in sync with the rest of the U.S. foreign policy establishment.

The first seam lies to the south, or sub-Saharan Africa. This is the tactical seam, meaning that in day-to-day terms, there’s an awful lot of connectivity between that region and CENTCOM’s AOR. That connectivity comes in the form of transnational terrorist networks that extend from the Middle East increasingly into sub-Saharan Africa, making that region sort of the strategic retreat of al Qaeda and its subsidiaries. As Central Command progressively squeezes those networks within its area of responsibility, the Middle East’s terrorists increasingly establish interior lines of communication between themselves and other cells in Africa, as Africa becomes the place where supplies, funds (especially in terms of gold), and people are stashed for future use. Africa risks becoming Cambodia to the Middle East’s Vietnam, a place where the enemy finds respite when it gets too hot inside the main theater of combat. Central Asia presents the same basic possibility, but that’s something that CENTCOM can access more readily because it lies within its area of responsibility, while sub-Saharan Africa does not. Instead, distant European Command owns that territory in our Unified Command Plan, a system constructed in another era for another enemy. Those vertical, north-south slices of geographic commands were lines to be held in an East-West struggle, but today our enemies tend to roam horizontally across the global map, turning the original logic of that command plan on its head.

Central Command’s challenge, then, is to figure out how to connect these two regions in such a way as to avoid having Africa become the off-grid hideout for al Qaeda and others committed to destabilizing the Middle East. By definition, such a goal is beyond CENTCOM’s pay grade, or rank, because it’s a high-level political decision to engage sub-Saharan Africa on this issue—in effect, widening the war. And yet solving this boundary condition is essential to winning the struggle in the Middle East. What the Core-Gap model provides Central Command is a way of describing the problem by noting that transnational terrorism’s resistance to globalization’s creeping embrace of the Middle East won’t simply end with our successful transformation of the region. No, that struggle will inevitably retreat deeper inside the Gap, or to sub-Saharan Africa.

Why is this observation important? It’s important because it alerts the military to the reality that success in this war won’t be defined by less terrorism but by a shifting of its operational center of gravity southward, from the Middle East to Africa. That’s the key measure of effectiveness. Achieving this geographic shift will mark our success in the Middle East, but it will also buy us the follow-on effort in Africa. You want America to care more about security in Africa? Then push for a stronger counterterrorism strategy in the Middle East, because that’s the shortest route between those two points.

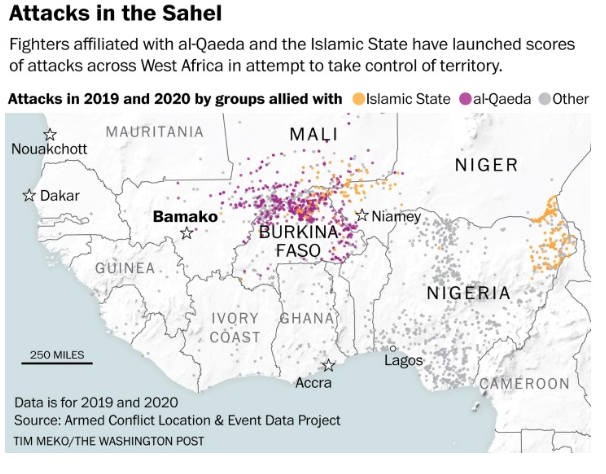

And from the Washington Post today:

Fighters appear to be coordinating attacks and carving out mutually agreed-upon areas of influence in the Sahel, the strip of land beneath the Sahara desert. The rural territory at risk is so large it could “fit multiple Afghanistans and Iraqs,” said Brig. Gen. Dagvin Anderson, head of the U.S. military’s Special Operations arm in Africa.

“What we’ve seen is not just random acts of violence under a terrorist banner but a deliberate campaign that is trying to bring these various groups under a common cause,” he said. “That larger effort then poses a threat to the United States.”

The militants have wielded increasingly sophisticated tactics in recent months as they have rooted deeper into Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso, attacking army bases and dominating villages with surprising force, according to interviews with more than a dozen senior officials and military leaders from the United States, France and West Africa.

To avoid scrutiny from the West, the groups are not declaring “caliphates,” officials said, buying time to train, gather force and plot attacks that could ultimately reach major international targets.

A coalition of al-Qaeda loyalists called JNIM has as many as 2,000 fighters in West Africa, according to a U.S. report released this month. The Islamic State in the Greater Sahara, which staged the 2017 attack that killed four American soldiers in Niger, is also thought to be hundreds strong and recruiting combatants in northeastern Mali.

“This cancer will spread far beyond here if we don’t fight together to end it,” said Gen. Ibrahim Fane, secretary general of Mali’s ministry of defense, whose country has lost more than 100 soldiers in routine clashes since October.

The warnings come as the Pentagon weighs pulling forces from West Africa, where about 1,400 troops provide intelligence and drone support, among other forms of military help. About 4,400 American troops are based in East Africa, where the U.S. military advises African forces fighting al-Shabab ...

Thomas P.M. Barnett Comments Off |

Thomas P.M. Barnett Comments Off |