Political Resilience Is Being Confident To Face Ugly Truths, Knowing Your System Will Survive The Encounter

Friday, February 5, 2016 at 11:08AM

Friday, February 5, 2016 at 11:08AM  AFTER AMERICA RODE A TIDAL WAVE OF ECONOMIC INTEGRATION AND EXPANSION FOLLOWING ITS CIVIL WAR (MOVING RAPIDLY FROM A SECTIONAL ECONOMY TO A TRULY CONTINENTAL ONE), A FRIGHTENING STRETCH OF BOOMS AND BUSTS IGNITED A LENGTHY PROGRESSIVE ERA (BREAKING FOR THE ROARIN' TWENTIES) WHEN POLITICAL ACTORS FROM BOTH PARTIES SOUGHT SYSTEMIC REFORMS - LEST THE COUNTRY SUCCUMB TO THE SORT OF RADICALISM LOOMING IN EUROPE (SEE FALLOUT OF WWI, CAUSES OF WWII). It was a frightening journey in many ways, with worried leaders concerned that the very nature of American democracy was at stake. But this is the usual price to be paid in return for a radical and lengthy expansion of economic activity, and it's one the world faces today after that quarter-century-plus boom that ended in 2008-09 and left the global economy with a bad hangover of toxic debt that is still largely to be processed.

AFTER AMERICA RODE A TIDAL WAVE OF ECONOMIC INTEGRATION AND EXPANSION FOLLOWING ITS CIVIL WAR (MOVING RAPIDLY FROM A SECTIONAL ECONOMY TO A TRULY CONTINENTAL ONE), A FRIGHTENING STRETCH OF BOOMS AND BUSTS IGNITED A LENGTHY PROGRESSIVE ERA (BREAKING FOR THE ROARIN' TWENTIES) WHEN POLITICAL ACTORS FROM BOTH PARTIES SOUGHT SYSTEMIC REFORMS - LEST THE COUNTRY SUCCUMB TO THE SORT OF RADICALISM LOOMING IN EUROPE (SEE FALLOUT OF WWI, CAUSES OF WWII). It was a frightening journey in many ways, with worried leaders concerned that the very nature of American democracy was at stake. But this is the usual price to be paid in return for a radical and lengthy expansion of economic activity, and it's one the world faces today after that quarter-century-plus boom that ended in 2008-09 and left the global economy with a bad hangover of toxic debt that is still largely to be processed.Per a solid NYT story of late:

Beneath the surface of the global financial system lurks a multitrillion-dollar problem that could sap the strength of large economies for years to come.

The problem is the giant, stagnant pool of loans that companies and people around the world are struggling to pay back. Bad debts have been a drag on economic activity ever since the financial crisis of 2008, but in recent months, the threat posed by an overhang of bad loans appears to be rising. China is the biggest source of worry. Some analysts estimate that China’s troubled credit could exceed $5 trillion, a staggering number that is equivalent to half the size of the country’s annual economic output ...

But it’s not just China. Wherever governments and central banks unleashed aggressive stimulus policies in recent years, a toxic debt hangover has followed. In the United States, it took many months for mortgage defaults to fall after the most recent housing bust — and energy companies are struggling to pay off the cheap money that they borrowed to pile into the shale boom ...

In theory, it makes sense for banks to swiftly recognize the losses embedded in bad loans — and then make up for those losses by raising fresh capital. The cleaned-up banks are more likely to start lending again — and thus play their part in fueling the recovery.

But in reality, this approach can be difficult to carry out. Recognizing losses on bad loans can mean pushing corporate borrowers into bankruptcy and households into foreclosure. Such disruption can send a chill through the economy, require unpopular taxpayer bailouts and have painful social consequences. And in some cases, the banks might find it extremely difficult to raise fresh capital in the markets.

Sounds like recent American history, yes? It's 2016 but there's still palpable anger over the Wall Street bailouts and far too many Americans still struggle with unsustainable credit debt. But, by way of comparison, the U.S. dealt with the financial crisis with genuine speed.

Yes, op-ed columnists are still arguing about the bailouts and the stimulus spending (the latter being somewhat irrelevant to curing a financial crisis), with plenty still arguing for more spending (like Paul Krugman). And we most certainly have endured a strange era of name-calling: remember when President Obama was a "socialist" in the eyes of his enemies?

But now we have a serious Democratic candidate for president in Bernie Sanders who embraces the Social-Democrat moniker, and he gets enough traction with that to force Secretary Clinton into making her own claims at the progressive label. On the other side, Republican candidates are struggling with the terms but reaching for the same sense of popular desperation - the feeling that the middle class has been under assault for years now. It's just that too many candidates in the GOP are having trouble separating that valid concern from the sort of anti-immigrant sentiment that is historically attached to such fears.

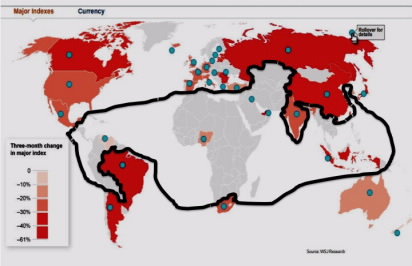

Still, all this shouting and posturing and name-calling reflects something positive: compared to the rest of the world, America was more confident in processing its toxic debt overhang. Plenty of work to be done, but the job is engaged. What the NYT article laments is the lack of similar progress elsewhere, and, in my mind, that progress reflects a political lack of confidence in the systems afflicted - one that prevents them from moving more aggressively because they fear the very fabric of their governments' political legitimacy might tear.

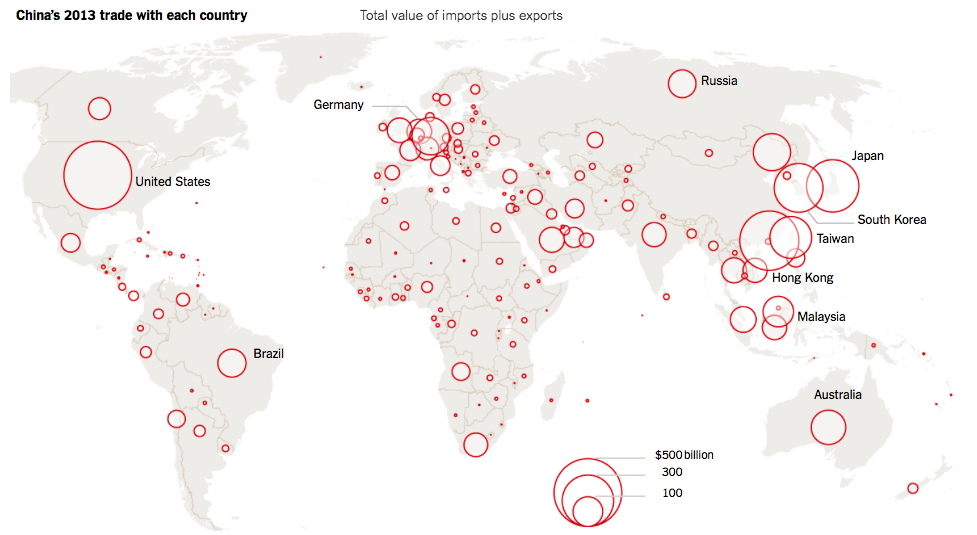

China is the scariest example in this regard. Per the chart above, we see just how integrated and important the Middle Kingdom has become with regard to the global economy's functioning. Scarier still is the damaging precedent set by neighboring Japan:

Japan, economists say, waited far too long after its credit boom of the 1980s to force its banks to recognize huge losses — and the economy suffered for years after as a result.

But Japan stalled out during the go-go nineties, so it could only do so much damage on a global scale. But, as the world went on a growth tear over the next decade and a half, the stakes today are so much larger - as is the poster-child for not facing the truth with enough alacrity - again, China.

Headline figures for bad loans in China most likely do not capture the size of the problem, analysts say. In her analysis, [one prominent local observer] estimates that at the end of 2016, as much as 22 percent of the Chinese financial system’s loans and assets will be “nonperforming,” a banking industry term used to describe when a borrower has fallen behind on payments or is stressed in ways that make full repayment unlikely. In dollar terms, that works out to $6.6 trillion of troubled loans and assets.

None of that was truly unexpected. You spend your way out of a financial crisis and you're simply delaying your day of reckoning - an essentially political process of regrading the economic landscape like the two Roosevelts (Theodore and Franklin) once did for the U.S. under similarly tumultuous circumstances (may I suggest Ken Burns' 14-hour documentary "The Roosevelts" on Netflix).

It's just that no one can spot that sort of leadership in China right now. We've seen some experts compare Chinese president Xi Jinxing to T.R. in terms of foreign policy machismo (largely on display only in the South China Sea), and Xi has definitely earned his corruption-busting stripes for his lengthy recent domestic campaign. But processing China's frightening large pool of toxic debt?

The looming question for the global economy, however, is how China might deal with a vast pool of bad debts.

After a previous credit boom in the 1990s, the Chinese government provided financial support to help clean up the country’s banks. But the cost of similar interventions today could be dauntingly high given the size of the latest credit boom. And more immediately, rising bad debts could crimp lending to strong companies, undermining economic growth in the process.

“My sense is that the Chinese policy makers seem like a deer in the headlights,” Mr. Balding said. “They really don’t know what to do.”

And that, my friends, is the biggest uncertainty right now in the global system. ISIS, for all its ferocity and atrocities, does not compare. Sanders/Clinton v Trump/Cruz/Rubio does not compare. The Brexit/Grexit/Whoxit? dynamic in the EU does not compare.

And this is where multiparty, pluralistic democracies rule - when they choose to. They can "throw the bums out." Heck, they're required to in the U.S. after 8 years - maximum (our presidential administration). Being able to apply the "clean slate" is a huge act of political resiliency, one that China, with its single-party state, is presently unable to employ.

And that is worrisome for the entire global economy as it continues to process the toxic overhang from that great global economic expansion that we all now remember so fondly.

China,

China,  US,

US,  finance,

finance,  global economy,

global economy,  resilience | in

resilience | in  Citation Post |

Citation Post |  Email Article |

Email Article |  Permalink |

Permalink |  Print Article

Print Article