Aired February 26, 2003 - 12:50 ET

BARNETT: Thank you.

WOLF BLITZER, CNN ANCHOR: The U.S. military is constantly transforming military capabilities to meet future global threats. A senior strategic researcher at the U.S. Naval War College, Thomas Barnett, is a big help in that regard. His latest article appears in the March issue of "Esquire" magazine, titled “The Pentagon’s New Map.” Mr. Barnett is currently working at the Office of the Secretary of Defense. He's joining us now live from San Diego, California.

Mr. Barnett, a very interesting article. Thanks very much for joining us.

You see this current struggle with Iraq within the broader issues of the gaps resulting from globalization. Give us the gist of your thesis.

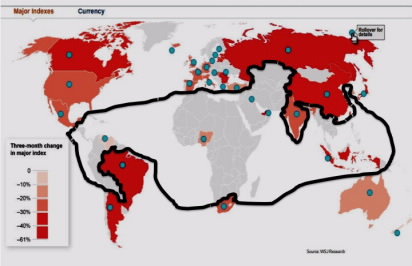

THOMAS BARNETT, PENTAGON ADVISER: Well, this new way of looking at the world begins with a simple series of observations. First, you look at where this country has sent its military forces around the world over the past 12 years, or basically since the end of the Cold War, a total of 132 cases. You draw a line around the majority of these cases, the regions where these situations have been concentrated, and you're really talking about the Caribbean rim, you're talking about most of Africa, you're talking about the Balkans, the Caucuses, central Asia, the Middle East, southeast Asia.

You draw a line around those regions of the world and you ask yourself, what's the common characteristic here that defines why we seem to be sending military troops into these regions time and time again in this era of globalization? And the basic argument I make is, these are the countries or regions that are having a hard time with globalization. In effect they can't integrate their national economies with a global economy because of repressive political regimes, endemic conflict, abject poverty, perhaps they just don't have the robust legal systems to attract foreign direct investment.

BLITZER: And so I was going to say, that's why you think a war with Iraq right now is not only inevitable and desirable, but clearly imperative for the United States and indeed for Iraq. That's also your argument?

BARNETT: Yes, because when you talk about the parts of the world that aren't integrating in this larger process we describe as globalization, it's very instructive to note that these are the places we're sending our troops again and again.

So you've come up with this new security paradigm that says, it's disconnectedness that tends to define danger in this era of globalization. And when you're talking about the Middle East, you're talking about a region of the world that has very little connectivity with the rest of the planet. Basically, they offer oil, and what we're trying to do is prevent terrorism from coming out of there.

BLITZER: But do you really believe, Mr. Barnett, that the U.S., with this military engagement, can transform that region, beginning with Iraq, into vital democratic robust nations?

BARNETT: Well, my argument is basically, we've got to shrink these parts of the world that are not integrating with the global economy, and the way you integrate a Middle East in a broadband fashion with the rest of the global economy is to remove the security impediments that create such a security deficit in that part of the world. And the biggest security impediment right now, I would argue, is the regime of Saddam Hussein. You move that out of the area, you eliminate that source of conflict, and hopefully, you can talk about integrating part of the world that over the past several decades has woefully underperformed economically. Basically the Muslim population represents something like 20 percent of the global population—only engages in about 4 percent of the trade.

So we've got to expand this dialogue, this interaction between the West and the Middle East beyond just oil. My argument is it's not the oil trade that we have with the Middle East that accounts for the enmity those regions feel for us; it's the fact that we don't have anything BUT the oil trade.

BLITZER: A provocative article in the new issue of "Esquire" magazine.

Thomas Barnett, thank you very much. We gave our viewers just a little bit—an appetizer, if you will—of what's in the thrust of your article.

Thanks for joining us.

What I remember: I was in San Diego doing an intra-governmental consulting gig (as War College profs, Bradd Hayes and I were there leading a visioneering exercise with a naval systems command, using the same process we had developed within Barnett Consulting LLC in our previous commercial work with the United Way of Southeastern New England—now known as the United Way of Rhode Island, thanks to our advice). The appearance on Blitzer’s show was arranged by Esquire’s PR firm, Dan Klores Communications. So I engineered a suitable break in the proceedings, stepped outside the naval facility and into a limo that took me to a ratty little local remote facility (dingy storefront in strip mall), where the tech threw up a pretty San Diego backdrop on a screen that even featured, if I remembered, the occasional commercial jetliner on final approach over the city skyline—on a loop). It was my first remote and it was hard. The tech said I wouldn’t want to watch the feed because the time delay meant both Blitzer’s and my own lips wouldn’t match up to what I was hearing—faster—over my ear bud. He warned that I would start trying to slow down my words to match my lips, making me sound drunk. So I went without any visual aid and simply stared into camera.

In the car ride on the way home, I called my parents to see if they caught my first-ever appearance on national TV, and the first thing my mom said upon answering was, “Your father and I both agree: TV adds 15 lbs.”

Without missing a beat, I turned to the invisible camera in my mind and quipped, “Folks—my mother!”

I saw the tape finally days later when I got home.

When I read the text today, my logic remains unchanged: You go after bad actors when you can muster the international will, but what you focus on in the aftermath ain't democracy but economic connectivity.

Tuesday, November 29, 2011 at 10:23AM

Tuesday, November 29, 2011 at 10:23AM