THE NOTION THAT GLOBALIZATION RESULTS IN CULTURAL HOMOGENIZATION ONLY SEEMS TRUE DURING ITS INITIAL "INVASION," BUT, OVER TIME, REGIONAL AND NATIONAL PILLARS INVARIABLY RECLAIM THEIR HISTORIC CULTURAL INFLUENCE AND MARKET TURF. We in America tend to view this as a "reversal" of globalization's tide, when it is nothing of the sort. It's simply local populations accepting globalization's connectivity while repopulating its content, and, in doing so, rendering it more applicable, tolerable, and entertaining. I've made this point for many years in my writing: virtually everyone in the world welcomes globalization's connectivity, but many - if not most - have a problem with its content (particularly when it emanates from culturally free-wheeling America). A few nations deal with this content mismatch by censorship, bans, and the like. But the smarter cultures adopt the media/connectivity models and then fill them up with their own unique content - eventually exporting that content abroad.

That is most definitely the case with Nigeria, per a NYT story:

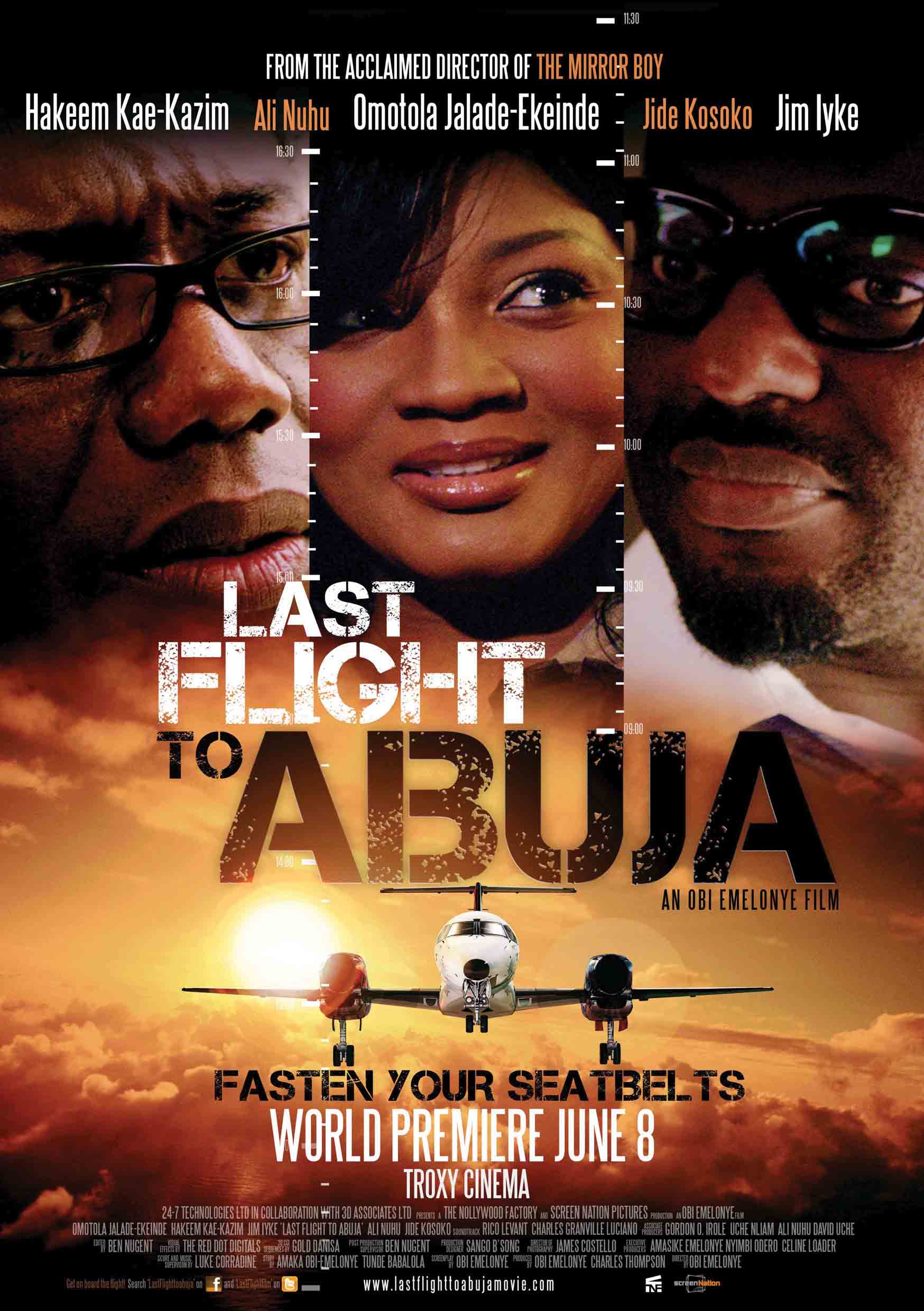

The stories told by Nigeria’s booming film industry, known as Nollywood, have emerged as a cultural phenomenon across Africa, the vanguard of the country’s growing influence across the continent in music, comedy, fashion and even religion.

Nigeria, Africa’s most populous nation, overtook its rival, South Africa, as the continent’s largest economy two years ago, thanks in part to the film industry’s explosive growth.

Notice how, when it's a regional pillar doing the "cultural imperialism," no one uses that term:

“The Nigerian movies are very, very popular in Tanzania, and, culturally, they’ve affected a lot of people,” said Songa wa Songa, a Tanzanian journalist. “A lot of people now speak with a Nigerian accent here very well thanks to Nollywood. Nigerians have succeeded through Nollywood to export who they are, their culture, their lifestyle, everything.”

But the key dynamic here, as noted above, is the repopulating of media networks previously dominated by outsiders with local content.

Nollywood generates about 2,500 movies a year, making it the second-biggest producer after Bollywood in India, and its films have displaced American, Indian and Chinese ones on the televisions that are ubiquitous in bars, hair salons, airport lounges and homes across Africa.

Nollywood succeeds by telling stories about the vast socio-economic transitions Africans are experiencing thanks to globalization's embrace:

Nollywood resonates across Africa with its stories of a precolonial past and of a present caught between village life and urban modernity. The movies explore the tensions between the individual and extended families, between the draw of urban life and the pull of the village, between Christianity and traditional beliefs. For countless people, in a place long shaped by outsiders, Nollywood is redefining the African experience.

In short, Nollywood's content represents a cultural coping-mechanism - a source of civilizational resilience amidst tumultuous change.

“I doubt that a white person, a European or American, can appreciate Nollywood movies the way an African can,” said Katsuva Ngoloma, a linguist at the University of Lubumbashi in the Democratic Republic of Congo who has written about Nollywood’s significance. “But Africans — the rich, the poor, everyone — will see themselves in those movies in one way or another.”

Best yet, Nollywood-as-Hollywood-cum-Bollywood knock-off is already replicating itself across the continent, resulting in even more localized and culturally rich content generation.

Nollywood has also created a model for movie production in other African nations, said Matthias Krings, a German expert on African popular culture at Johannes Gutenberg University.

In Kitwe, Zambia, local filmmakers were recently making their latest movie in true Nollywood style: a family melodrama shot over 10 days, in a private home, on a $7,000 budget. Burned onto DVD, the movie will be sold in Zambia and neighboring countries.

Acknowledging the influence of Nigerian cinema, the movie’s producer, Morgan Mbulo, 36, said, “We can tell our own stories now.”

And that's how globalization should work: global connectivity spreading capabilities and those expanding capabilities allowing for local developments that suit local tastes, cultural requirements, and the social issues of the day.