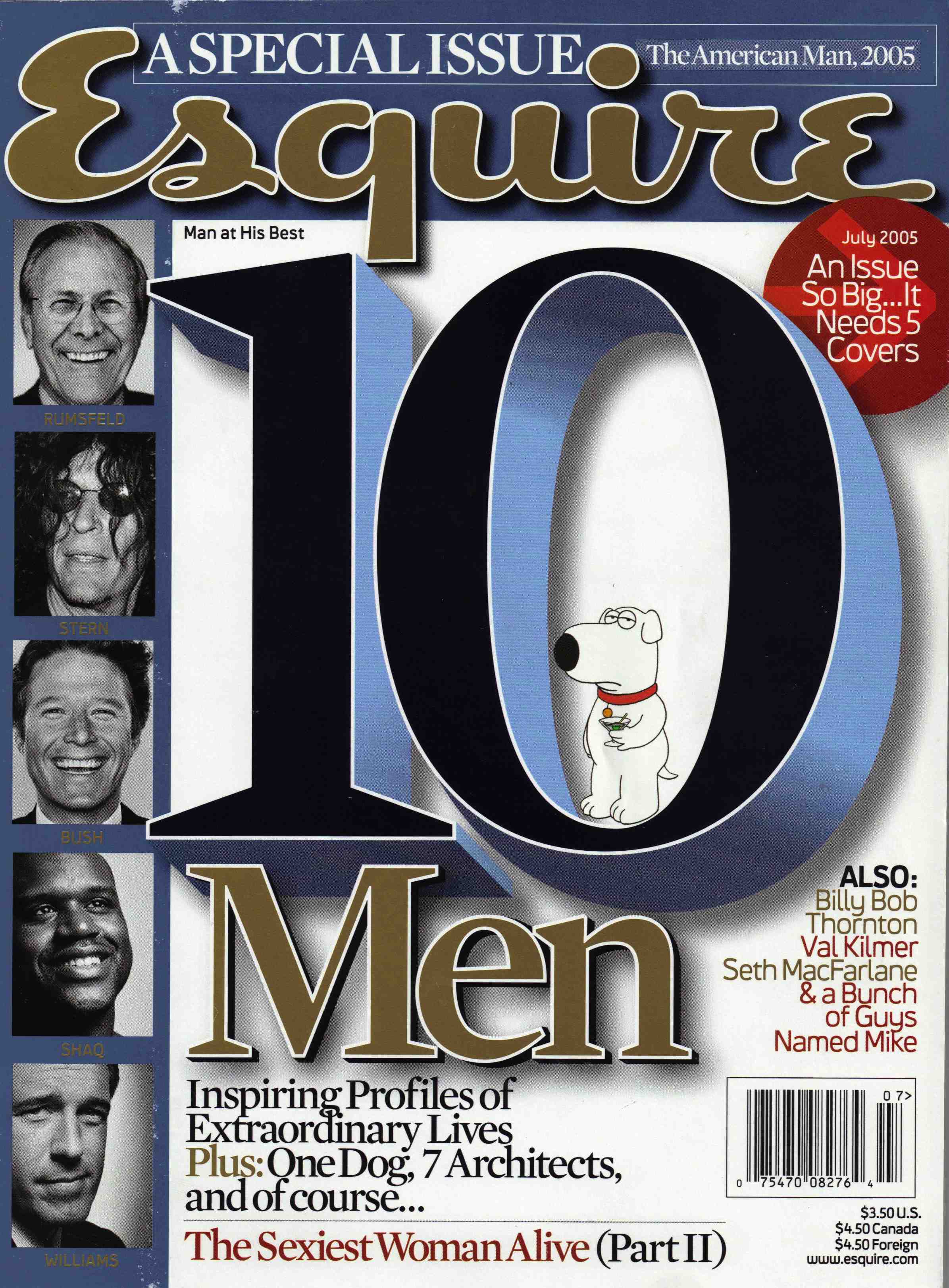

Blast from my past: "Old Man in a Hurry" (2005)

Saturday, August 21, 2010 at 12:01AM

Saturday, August 21, 2010 at 12:01AM

Old Man in a Hurry

by Thomas P.M. Barnett

The secretary of defense's suite of offices in the Pentagon is on the third deck, outermost, or E-ring of the five-sided building, in the wedge between corridors eight and nine. It's one of the older wedges, on the far side of where the new ones are to be found or are being renovated, and on the opposite side of the building, one thousand feet away, from the section that was destroyed on September 11, 2001.

Room 3-E-880 overlooks the Potomac in the direction of the White House and Capitol, but the famous skyline is hard to recognize on a rainy afternoon through the queer greenish tinting that covers all the windows here. You're tempted to adjust the picture on your screen, but this special coating repels electronic surveillance and denies enemy spies a view inside the Building.

The secretary's inner sanctum is a threshold so secure that you have to surrender your cell phone and BlackBerry to cross over. SecDef's office is classified a SCIF, meaning a sensitive compartmented information facility, or what people in the business call a "vault." Being inside a SCIF means you can engage in the most classified of conversations without fear, and when you leave, the Maxwell Smart doors close heavily behind you.

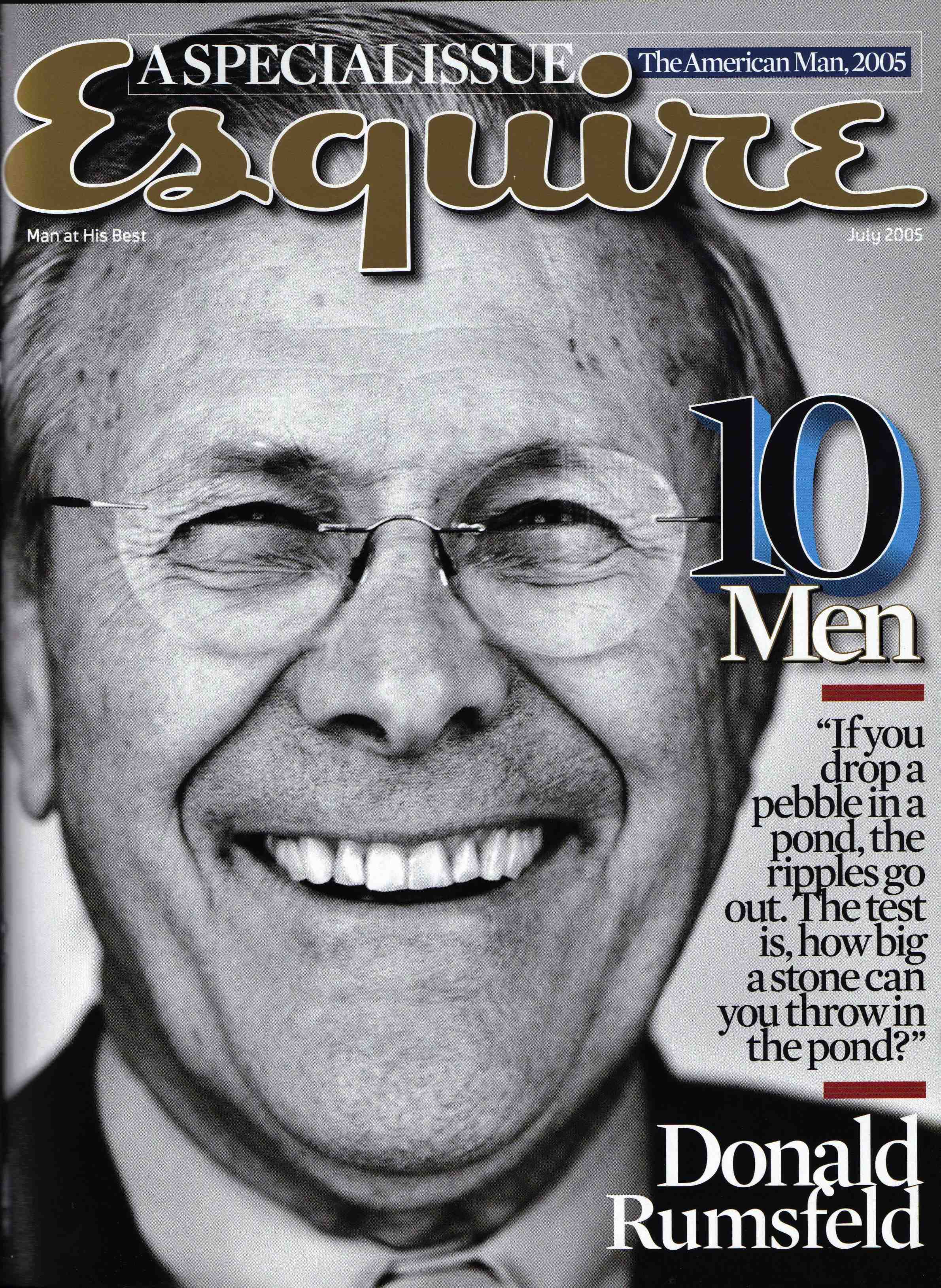

It is from this suite of rooms that Rumsfeld has become one of the most loathed and revered men in the world. The man is too impatient, too damned arrogant, too beyond politics, and just too stubborn for his own good. He is the famously combative, two-time SecDef (both youngest and oldest ever) who chews up and spits out experienced reporters in what are easily the most skillfully performed press conferences since John Kennedy walked the earth. He has brilliantly executed a couple of wars, and badly botched a peace. Let us stipulate all these truths just to move the conversation along.

But something else has been going on in this office, and it's nothing short of the most profound transformation of the U. S. military since World War II--a historic process that will, paradoxically, yield a force Americans haven't seen since our frontier days. The United States had one Defense Department on January 20, 2001, and it will have a very different one by January 20, 2009. Donald H. Rumsfeld, thirteenth and twenty-first secretary of defense, is the reason why.

He is known to his personal aides and longtime colleagues as a "deep diver." Confront him with a tough new bureaucratic nut to crack and he goes deep--waaaay down--on the subject until he feels he gets it sufficiently to assemble the right smart people to handle the job. It doesn't matter how much time he appears to be wasting on the process; he simply doesn't move ahead until he's got the picture in his head of what "this thing"--whatever it is--is really all about. He will keep the U. S. military's most powerful men sitting around a table for however long it takes for that to happen.

He is known to his personal aides and longtime colleagues as a "deep diver." Confront him with a tough new bureaucratic nut to crack and he goes deep--waaaay down--on the subject until he feels he gets it sufficiently to assemble the right smart people to handle the job. It doesn't matter how much time he appears to be wasting on the process; he simply doesn't move ahead until he's got the picture in his head of what "this thing"--whatever it is--is really all about. He will keep the U. S. military's most powerful men sitting around a table for however long it takes for that to happen.

Rumsfeld's first deep dive of his second tour as secretary of defense started on the Sunday after the Saturday he was sworn in, January 21, 2001, at a meeting he called of his most trusted advisors, all of whom he had known for years, some since he was a congressman from Chicago in the 1960s, one from college fifty years before. The meeting took place in room 3-E-880, and for several participants, it was the first time they'd been together again in that vaunted space since January 1977, in the last days of the Ford administration.

Rumsfeld had been reassembling his kitchen cabinet since the day the president called him at his ranch in Taos, New Mexico, in late December and offered him the job. He said, Thank you, Mr. President-Elect, and immediately called Marty Hoffman, who had been his secretary of the Army the first time around and who also has a place in Taos. Marty was a classmate at Princeton and is one of Rumsfeld's best friends. "Can you bring together some of the people who helped and worked with me the first time around?" he asked Hoffman.

"Defense transformation" was the train already leaving the station by the time Rumsfeld was sworn in on January 20, 2001. Trapped in cold-war thinking and armed with contingency plans that had not been reviewed for years, sometimes decades, the Pentagon spent the 1990s scrambling from one overseas crisis intervention to another, in the process piling up mountains of "supplementals," or ad hoc requests for additional funding from Congress to cover unexpected operations. As one of Rumsfeld's senior aides, Pete Geren, told me in 2002, "When your 'crisis response' lasts several thousand days, it stops being a crisis and starts being a feature of your strategic landscape."

So transformation was a "mature debate," as they say in the Building, but for Rumsfeld it was too far tilted in the direction of high-tech weaponry rather than changes in "tactics, techniques, and procedures," which is a favorite military phrase of his. Because Rumsfeld was identified with space and missile defense from the time in the 1990s he spent chairing congressional commissions, everyone thought his definition of transformation would be tech heavy, but it hasn't turned out that way.

To change the culture of the Pentagon, he'd start with people, not technology. He knew that achieving any kind of meaningful transformation was going to be damn near impossible without new people, given the entrenched interests in the Building and the old ways of thinking. For new thinking, Rumsfeld sought out old friends.

In addition to Marty Hoffman, there was Tom Korologos, the grand old man of Washington politics, who had managed his confirmation in 1975 and would do the same this time, too; Paul Wolfowitz, the ideologue in the room, who would come on as his deputy; Steve Cambone from National Defense University, who was the new boy, having met Rumsfeld in the 1990s while working on the Rumsfeld-led Space Commission and Missile Defense Commission; Bill Schneider, Rumsfeld's favorite gray eminence, who would later become chairman of the Defense Science Board; and Ray DuBois, who had met young Congressman Rumsfeld in 1967 when he was working as an intern to Chuck Percy, the senator from Illinois, and then went with him to the Pentagon. He would become "mayor" of the Pentagon this time around.

"I was all of twenty-one when we met," says DuBois, "and I told friends at the time that I had met this guy named Rumsfeld who had been captain of the wrestling team at Princeton. I said, 'He's a young man in a hurry.' So I worked for a young man in a hurry when he was forty-three years old and became secretary of defense, and now I'm working for an old man in a hurry. Same guy, different age, same impatience, still in a hurry."

There was great excitement around the table. "Can you believe it? Can you believe we're all back?" was the feeling. And there was a growing sense of the enormous task that lay ahead.

Rumsfeld, at the head of the long table, ran the meeting himself, but in his typically indirect way; clearly he had an agenda, but he did not reveal it, instead wanting to tease ideas out of the assembled brains. Immediately clear was that this was not a meeting about imminent threats or weapons systems but rather a wholesale reform of the "business side" of the Pentagon. By this time, Rumsfeld had spent two decades as a CEO, at G. D. Searle & Co., General Instrument Corporation, and Gilead Sciences, and he had become a corporate technician, a philosopher of that kind of stuff, and if he had an abiding ideology it was efficiency.

Rumsfeld tossed out a series of strategic questions, trying to define the job ahead. "What should be the main transformation initiatives in my tenure?" he asked. Once they agreed on what those changes would be, Rumsfeld was intent on generating an immediate sense of momentum and inevitability. He continued. "Do we have the right projects in the pipeline? Do we have the right number of troops? I've read the reports, so I know that we have too much infrastructure. Do we need to shut down bases?" He turned to Wolfowitz. "What issues in the world do we want to address and shape from the start?"

The first goal would be reshaping Rumsfeld's massive office (the Office of the Secretary of Defense, or OSD) and recasting its "civil-military" relationship with the Joint Staff and all four military departments, something that had been impossible during the cold war but was imperative now to adapt the Pentagon to the changed world. The U. S. military has been struggling to build a single integrated force out of the Army, Air Force, Navy, and Marines ever since the Berlin Wall came down. Why make the effort? Why change the winning hand? Because these forces were constructed to meet old threats, not new ones, and the United States no longer needed and could no longer afford four militaries, and the world couldn't afford an America that was not prepared to fight future wars effectively. The main impediments to this idea would be the services themselves, dominated as each was by senior officers who had risen to the top by protecting their branch's slice of the pie from the "sister services" and, by doing so, had perpetuated such belt-and-suspender traditions as each service sporting its own particular brands of aircraft. Why? Apparently, a single plane wouldn't do--even for the "joint force," in which all services allegedly fought side by side in a seamless fashion.

To achieve integration, Rumsfeld announced that they would push for another BRAC (Base Realignment and Closure Commission), arguing that they must succeed where secretaries William Perry and Bill Cohen had failed under Clinton.

The underlying assumption to all at the table was that the dimensions of the job were such that there was simply no way that full implementation could be reached before a second term. One day after a new president had been sworn in, coming into office with the shakiest of mandates, Rumsfeld was talking about an eight-year plan.

And transformation was born.

Just as quickly, it almost died.

Rumsfeld pops out of his chair with the speed of the weekly squash player he still is at age seventy-three and strides over to shake my hand with a big, welcoming smile on his face, employing the enthusiastic, familiar tone one associates with longtime acquaintances. "Hey, how are ya? Nice to see ya!" I'm surprised by how short he is, as I can look right over his head.

In advance of this meeting, I have talked to three joint chiefs (Navy, Air Force, Army), two undersecretaries (policy and intel), Rumsfeld's chief of staff, Larry Di Rita, aka "Heavy D," who is also SecDef's press secretary, and others close to Rumsfeld, including Ray DuBois, the mayor of the Pentagon. It is a testament to his penchant for preparation that Rumsfeld reviewed the transcripts of all these interviews beforehand.

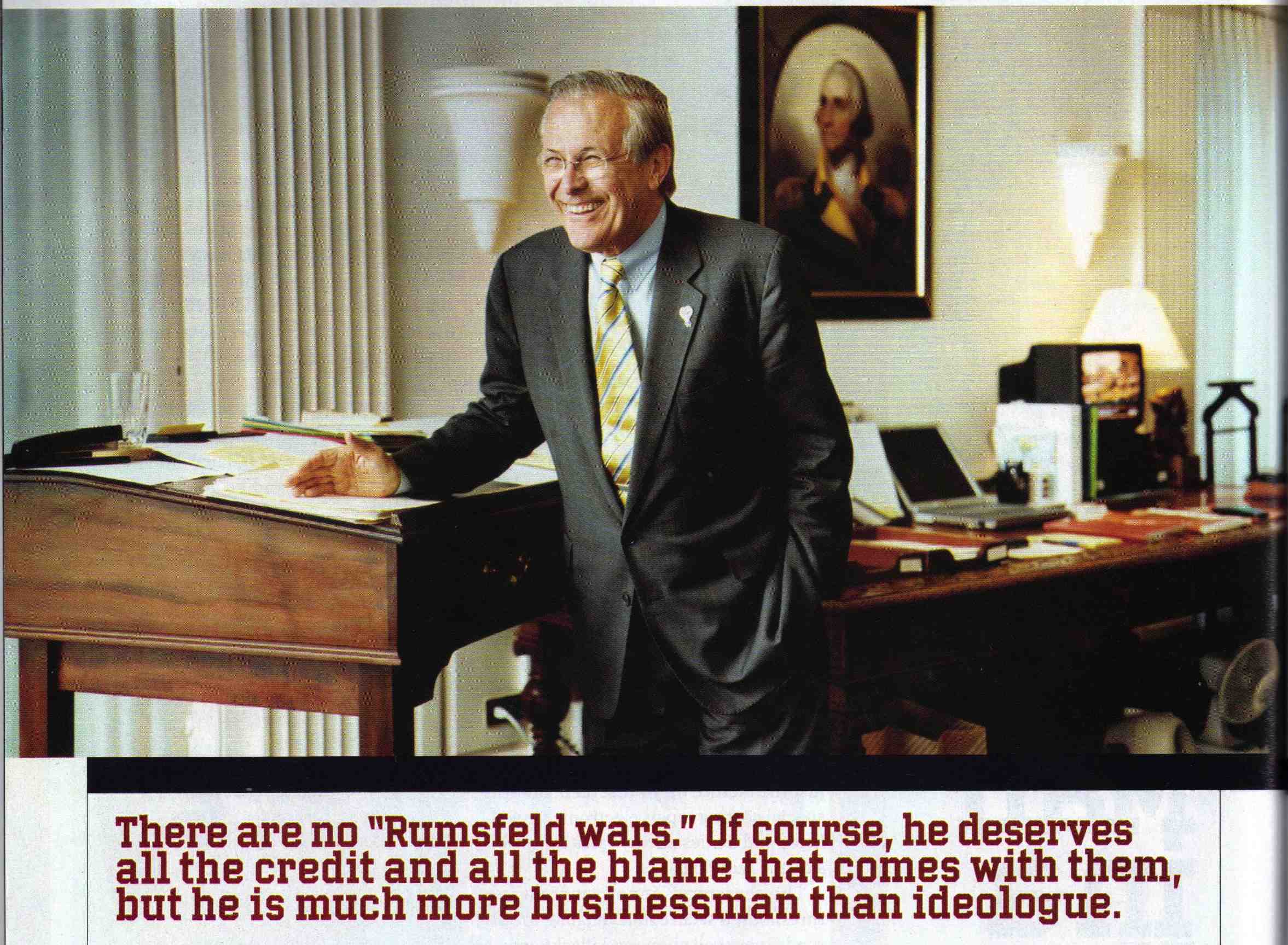

With the blinds drawn, I can't tell if it's day or night as I enter an office that could pass for a small ballroom. Like the man, the room has a definite old-school feel about it--a massive wooden desk smack-dab in the middle, lots of rugged Remington-style bronze statues of Indians and buffalo, a bronze bust of Winston Churchill. This is a room you smoke cigars in and decide the fate of the free world.

We sit down at a long table on the far side of the room. He's wearing a zippered fleece vest over his shirt and tie, Mr. Rogers style, and he is very at ease. He asks several questions that he already knows the answers to, testing and probing, as is his way. When he speaks, his hands are in constant motion, tearing apart and rearranging invisible things, physically grappling with the subject at hand. There's a lot to grapple with these days.

Rumsfeld is warming to the topic of how a transformed military looks and feels on the battlefield.

"One of our folks made a comment the other day, and I called him on it and said, 'You said you have 20 percent of something you need,' and he said, 'Yeah.' And I said, 'You have 100 percent of what you have, and you've decided you need something else.' And he said, 'That's right.' And I said, 'Well, when did you decide that?' and he said, 'Last week.' And I said, 'Well, what you need to do is not say that you have 20 percent of what you need. What you need to do is adapt your tactics, techniques, and procedures to fit what you have, because that's what you asked for. And you now have it. That's what you wanted, and now you've got it. And now you've got to go do what you do with what you have and make sure that you're protecting lives and achieving goals by designing tactics, techniques, and procedures to fit it.' There's nothing wrong with saying you want more of something or something different. But you're against a thinking enemy; the enemy's going to change. If you are successful and you get a body armor that will stop a certain size slug, he's going to come at a different angle or he's going to get armor-piercing slugs. It doesn't take a genius to figure that out. If you get a jammer to take these frequencies out, they're going to go to these frequencies or they're going to roam or they're going to do something different. That is the nature of it.

"And you will never have the ability to defend against every location and every conceivable technique at every moment of the day or night with stuff. We would sink a country with that stuff! So that's what the commander's gotta do. He's gotta use his head."

This sounds dangerously close to the kind of talk that got Rumsfeld in hot water late last year, when a soldier complained to him about a lack of armored vehicles on the ground in Iraq, and he replied, "You go to war with the Army you have, not the Army you might want or wish to have." It struck many as grossly insensitive and had congressmen calling for Rumsfeld's head. So if nothing else, he is an unrepentant cuss.

Moreover, the treatment he subjected the poor 20 percent bastard to is known in Rumsfeld's Pentagon as wire-brushing. This particular officer got off pretty easy, actually, because you really don't want Donald Rumsfeld after you with a wire brush. But the wire brush is an integral tool Rumsfeld uses in his deep dives.

Giving someone the wire brush means chewing them out, typically in a public way that's demeaning to their stature. It's pinning their ears back, throwing out question after question you know they can't answer correctly and then attacking every single syllable they toss up from their defensive crouch. It's verbal bullying at its best, and when you're a ranking civilian and we're talking some military officer, you can certainly get your rocks off doing it because--hey--they have to take it from you, what with civilian control and all. Plus, there's a certain brand of military officer who really keeps it in--really tight inside. Those guys you can play like a fiddle.

Rumsfeld has created enemies in the ranks with this tactic, and during the Afghanistan campaign, he wire-brushed someone big right out of the service. Marine Lieutenant General Greg Newbold held the all-important position of J-3 on the Joint Staff during that war, meaning he was the flag officer overseeing combat operations from the Pentagon. In that role he routinely briefed the press on the progress of the war. One day, he announced that the Taliban had been "eviscerated." Immediately signaling Rumsfeld's displeasure at this potentially explosive choice of words, General Richard Myers, who had recently been named chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, said, "We were surprised that a marine even knew what eviscerated meant."

Newbold knew he was in for it. Soon after, he was jerked back from press briefings and replaced by a more savvy Navy admiral. Subjected to some intense wire-brushing, Newbold chose to end his military career by requesting early retirement. Later asked about Rumsfeld's "abusive" ways, Newbold cited an even bigger concern: that Rumsfeld's tough style intimidated some generals from doing their jobs right. As he put it, "If the environment's intimidating and suppressive, if it demeans, people tend to clam up."

There are ways to parry the old man's wire-brushing, of course, and most serious military leaders have that sort of right-back-up-yours-sir! kind of patter down. Take, for instance, a three-star general who's briefed Rumsfeld a half dozen times. This guy's led men into battle, so the old man has nothing on him. Well, one day they're going back and forth and the general just stops him dead. He says, "Sir, I don't know why it is we get along so well. I've got a big family and you've got a little one. I'm an army ground-pounder and you were a stinkin' navy pilot. I like to use little words and you like to use big ones."

This guy's wire-brushing back. He's giving the old man some guff. He's saying, I'm not afraid of you. Rumsfeld responds to this, he respects it.

Then the general clinches the deal. "So I've finally figured out why we get along so well," he says. "We've both run with the bulls at Pamplona!"

Rumsfeld shrieks in delight and then launches into a fifteen-minute reverie about the time he ran with the bulls. And for fifteen glorious minutes, he put away the goddamn wire brush.

Having been told by the Bush-Cheney ticket in 2000 that "help is on the way," people in the military expected a nice fat budget amendment for 2002, a pile of money they could use to begin to make up for all the "procurement holidays" taken by the soft-on-defense Clinton crowd. But Rumsfeld delivered only $18.4 billion--peanuts given the demand. Many in the defense community in the Pentagon and on the Hill started whispering about how the old man had lost his first bureaucratic battle, and badly. The "experienced hand" just looked old and lost all of a sudden, and his never-ending Friday-afternoon bull sessions about the meaning of transformation just seemed goofy.

But in Rumsfeld's view, he was preparing the bureaucratic battlefield in a way no other SecDef had before him. People thought Robert McNamara and his "whiz kids" had come in with an agenda for change under Kennedy, but their ambition was nothing compared with Rumsfeld's. He wanted to change it all: breaking up and reassembling every cold-war process for planning there was and making it lighter, faster, simpler, leaner.

Rumsfeld's first Quadrennial Defense Review in spring 2001 highlighted the concept of "deter forward," reflecting his belief that just having the force was one thing but being able to use it rapidly and decisively was another. Rumsfeld didn't want to deter America's enemies with the stuff we had over here but with the threat of what we could do with it over there--before the enemy had a chance to act.

Today, we call that concept by the far more direct term of preemption. A preemptive force can't take weeks to amass its personnel, much less months to send over all the tons of stuff that force might use. One thing that really sticks in Rumsfeld's craw is that the Pentagon was forced to bring back to the U. S. roughly 90 percent of what it had shipped over to the Persian Gulf to fight the first Iraq war with Saddam back in 1991. ("We would sink a country with that stuff!") That's how huge and sluggish the pipeline was: By the time the war had ended, we had enough stuff over there to fight nine more wars. And they brought it all back! Dammit, there was your Exhibit A in why we couldn't go on like that anymore.

The one question Rumsfeld purposefully avoided in all of his early mind-melds with staffers and generals was "To what end?" Believing that future enemies and future wars are too hard to predict, and that he was a businessman who would leave the war to the warriors, he made little effort to dive deep on that question. So the Pentagon planning process defaulted on that score to the neocons, Wolfowitz and his undersecretary for policy, Douglas Feith, who, at that point, had China in their crosshairs and a distinct aversion to Bill Clinton's sloppy attempts at nation building, Ã la Somalia and Haiti.

But so alien and unpopular were Rumsfeld's ideas, so out of sync was he on Capitol Hill, and so loathed was he by the flags and the generals that by Labor Day 2001 The Washington Post had all but announced a write-in contest for his successor, so certain were the cognoscenti that the old man would be the first Bush Cabinet member jettisoned. Gone by Christmas was the word.

But the terrorist attacks of September 11 would change all that, providing Rumsfeld's means with a very definitive end--the global war on terrorism. This war would become the proving ground, the laboratory, for Rumsfeld's transformation. Absent 9/11, transformation would have remained nothing more than a bureaucratic slogan. Absent 9/11, Donald Rumsfeld would be back on his ranch right now, rearranging the deck chairs on his back patio.

And since 9/11, no one in Pentagon history has used people like Rumsfeld has, and he's broken more rules and requirements than anyone thought possible.

When the president wanted the Taliban dislodged in Afghanistan as quickly as possible after 9/11, Rumsfeld backed General Tommy Franks's quick-and-dirty plan using an unprecedented mix of Special Forces, precision bombing, and CIA paramilitaries to exploit the on-the-ground capabilities of the anti-Taliban Afghani warlords and their forces. That experiment proved to be an eye-opener for Rumsfeld regarding the potential of Special Operations Command (SOCOM), and he quickly anointed the Tampa-based command as the lead Combatant Command in the global war on terrorism, taking what had always been a bastard-stepchild command that supported other commands and instantly turning it into one that now receives support from others. In the Pentagon, this was profound, like the rich father designating his chauffeur's son as his new heir.

By doing so, Rumsfeld not only transformed the role of SOCOM, he designated it as a cannibalizing agent within the U. S. military, saying to the rest of the armed forces: Go be more like them!

In the summer of 2003, Rumsfeld skipped over an entire generation of army senior generals to bring a four-star "snake eater" out of retirement to serve as his army chief of staff. Plucking General Pete Schoomaker from his retirement ranch nearly three years after he left the service as the boss of Special Operations Command was a serious kick in the pants to a hidebound Army that was struggling to transform itself under General Eric Shinseki, who, despite coining the term transformation, had fallen out of favor with Rumsfeld for, as one senior aide put it, becoming too fixated on improving the Army's efficiency in combat without questioning the relevance of the capabilities he was developing, as in, Great force, wrong war.

Schoomaker was down in Texas meeting with one of his ranching partners (everybody in this crowd, it seems, has a ranch) when he got a call on his cell phone. At first he thought it was a joke. "You've got to be kidding," he told Rumsfeld. "I'm not interested."

"That's not a good enough answer," Rumsfeld replied. "You've at least got to come talk."

So Schoomaker drove twenty-one hours straight back to his home in Tampa and then immediately flew up to Washington and spent the weekend with Rumsfeld. "By the time we got through talking . . . you get to a point where it's your duty to do things," says Schoomaker. "It's totally illogical. My wife, she thinks it's nuts."

Now Schoomaker is redesigning the Army's century-old division structure (fifteen to twenty thousand troops each) into something far more flexible and modular, or what he calls "brigade units of action" (thirty-five hundred to four thousand troops each). That's eighteen divisions, a cold-war structure, a structure for fighting the Russians, morphing into almost eighty brigades to face new enemies, brigades that are interchangeable among the active-duty force, the Army Reserves, and the National Guard. This is nothing less than returning the Army to its frontier days of cavalry-sized field units and leaving behind the division-driven history of two World Wars and the entire cold war. In a generation, the divisions will remain only as ceremonial vestiges of a type of war that no longer

exists. That's the idea anyway.

In return, Schoomaker made Rumsfeld promise that there'd be no divisions cut (so the manpower pool wouldn't change) and that he'd buy the general some "head room" with thirty thousand extra active-duty troops. Rumsfeld agreed, even as he knew he'd catch hell from Congress for having to admit the Army needed more men as the insurgency heated up in Iraq in the summer of 2003. After all, Eric Shinseki's parting shot to Rumsfeld had been to testify that the Pentagon had vastly underestimated the number of ground forces needed to secure postwar Iraq. Schoomaker told me that Rumsfeld went to the president directly on that one.

And to emphasize the importance of getting the people right before talking about the weapons, Schoomaker got Rumsfeld's promise to push back the production of the Army's superexpensive, all-encompassing Future Combat Systems to the latter years of the second administration to give the general additional time to boot up the new brigade structure. Rumsfeld agreed without question.

In the Building, this is providing what they call "top cover." Get past the wire-brushing, bond with the guy, and he'll go to the mattresses for you.

In room 3-E-880, Rumsfeld is talking about the brief that let him know what a mess there was to clean up. It was about a month after he was sworn in, and he had demanded to get a presentation on, "Where are the levers in the building? Not just where are they, but who pulls them? And what are they connected to?" What he saw that day is now called the Levers Brief.

Walking into his conference room, participants remember the walls being covered with giant charts full of boxes and arrows and lines and flow diagrams galore. Conveyor belts like crazy, like something out of I Love Lucy. "I looked at all these conveyor belts that seemed like they were loaded six, eight years ago," Rumsfeld says, "and they were just chugging along, and you could reach in and take something off, or put something on, but you couldn't connect the different conveyor belts. Each process had a life of its own and drivers that were disconnected from the others, and it was really just stark for me to see it that way, having been in a company where you could make things happen."

That day taught him that he had to change the entire culture of long-range planning throughout the Building, not just within his office. Once he had the right people on both sides of the process--both military and civilian--he had to create a new venue for these two sides to fight out budgetary and policy decisions in an integrated way. Because there are lots of brawls to get out of the way. Otherwise, you still end up buying for four different forces and then trying to operate them in the field as though they're an integrated whole when they're not. The result is that you always end up with a force that's driven more by budgetary considerations than it is by policy goals, when in the rest of the known universe, strategic thinkers will tell you that it makes much more sense for policy to drive budgetary choices, as in, "I want to do this, so I buy that." What the Pentagon has had for decades is the complete opposite, as in: "I want to buy that, so I can only do this."

As they say, when all you have is a hammer, the entire world starts to look like nails.

Thus, Rumsfeld's fight club was born. It's a secret society, and it's called the Slurg.

The Senior Level Review Group consists of eighteen top-drawer members: The secretary, the deputy secretary, the three service secretaries, the five undersecretaries, the six joint chiefs, the general counsel, and the assistant secretary for public affairs. What's so magical about eighteen? That's how many fit around the table in Rumsfeld's conference room. Six more members sit against the wall. It's not written down or anything; they just know to sit against the wall. The additional six are the assistant secretary for legislative affairs, the director of administration and management (the "mayor"), the assistant secretary for networks and information integration (the computer geek in chief), the director of program analysis and evaluation, SecDef's senior military assistant, and his senior special assistant. That's the two dozen regulars. Additional senior players drop in now and then as required.

Of course, it wouldn't be a Rumsfeld invention if it didn't have a bunch of rules attached to it, as Rumsfeld is famous for his rules.

The first rule of the Slurg is: You do not talk about the Slurg.

This secrecy is crucial. Top leaders, both military and civilian, need to be able to speak freely without creating, as Rumsfeld told me, "chatter about, Gee, this guy said something dumb and he proposed this." Those kinds of leaks can set off a lot of useless bureaucratic skirmishes down below. As one participant put it, "Because people were meant to speak their minds, you have to have someplace where they can be passionate on an issue." Or, as Rumsfeld puts it, "You have to have a process where people are confident they can talk, they can take risks, they can speculate on things and raise questions."

The second rule of the Slurg is: You DO NOT talk about the Slurg!

During the Clinton administration, the biggest and most important discussions occurred in the Tank, or the conference room where the six joint chiefs regularly meet. Under Rumsfeld, you never hear about the Tank anymore. It still meets. It's just not where the biggest decisions are made.

And that's crucial. Because the Tank is military territory, a space the secretary enters now and then but where he cannot run the show, because by tradition the Tank is where the chairman rules. Early in the first Bush term, Rumsfeld participated in a Tank session where some strong words were spoken, and the next day those words appeared in the media. To this day, one of the only two chiefs still serving from that time, Admiral Vern Clark, swears that it wasn't one of his colleagues who talked out of turn but one of the "straphangers," a military term for the personal aides who sit along the wall. After that, meaningful Tank sessions involving Rumsfeld became far less frequent.

No straphangers are allowed in the Slurg.

The third rule of the Slurg is: If you don't show up, you don't get to fight.

If the principal doesn't show up, then his seat at the table is forfeited for that session. You can't send a note taker to report back, and only a few key players are allowed substitutions under duress, meaning a vice-chief of staff can sub for the chief, but nobody lower than that.

The fourth rule of the Slurg is: No SecDef, no Slurg.

Rumsfeld once let Wolfowitz chair a Slurg in his absence, and when he got the debrief on it, he quickly decided that that would be the last Slurg to occur without his being present to steer things. The old man has a very distinct definition of what constitutes being "on topic."

The fifth rule of the Slurg is: One fight at a time, and fights will go on as long as they have to.

Rumsfeld decides the Slurg's agenda in advance of each meeting, but once things open up, he often just sits back and lets people go at it in front of him, intervening little in the process. Participants know to keep it civil and that personal rivalries are supposed to be checked at the door. But it's pretty freewheeling, and the meetings routinely drag on for more than two hours. Decisions are hammered out only in the roughest sense, as the ultimate calls reside with Rumsfeld himself, who often makes up his mind afterward and transmits his decision in one of his "snowflake" memos, so named because they fly off his desk in a flurry.

The sixth rule of the Slurg is: When the war fighter's involved, the war fighter's invited.

When the agenda touches upon subjects with big implications for the combatant commanders, or the four-star admirals and generals who command the forces in the major regional commands, then they're invited to a special, expanded version of the Slurg called the SPC, or the Strategic Planning Council.

Those are the basic rules, and there are no others. That is also a rule.

The Slurg has become the birthing room for something called the Joint Capability Integration and Development System. In plain English, the Slurg is the venue in which senior civilian officials and military officers have begun to engage in up-front comparisons of each service's acquisition strategies. That means head-to-head competition between programs in a rigorous environment that focuses on capabilities, not service shares. The Slurg makes the JCIDS (jay-sids) possible by getting all the necessary players around the table and forcing a truly "joint" discussion: joint among the services, joint between the civilian and military sides of the house, and joint between the force provider (Pentagon) and the force consumer (Combatant Commands).

This is the Holy Grail of jointness, or the historical process of operational integration among the services that stretches back to 1986, when Congress passed the Goldwater-Nichols Act in response to--among other things--the embarrassment of the 1983 invasion of Grenada, a comedy of interservice errors that could have resulted in the Bay of Pigs if there had been any competent enemies on the scene. Goldwater-Nichols sought to force greater integration and cooperation among the four services by diminishing the power of the service secretaries and increasing the power of the chairman of the Joint Chiefs and the various regional battle commanders. To a certain extent it's succeeded, as the four services now "fight joint" even if they don't "buy joint."

JCIDS, then, is the quest to create future weapons systems and platforms that are joint from the start, not service-specific capabilities that are later forced to adapt to one another, probably once a war is already underway. If jointness were a religion, then the concept of being "born joint" would be the equivalent of the Immaculate Conception--an article of pure faith.

The very secret Slurg is the Round Table of jointness. It is the altar of transformation. It is a very exclusive room. It will go down as the single biggest organizational legacy of Rumsfeld's reign.

Rumsfeld is leaning forward, almost standing up out of his chair, and he's talking about the ongoing experiment of Iraq. "We've got people out there who are so good, and they've got the guts to call audibles, and they do," he says. "And I think it's admirable. I mean, the idea that the president of the United States, the secretary of defense, or the combatant commander in Tampa could tell our people in Iraq or Afghanistan what they're supposed to do when they get up in the morning just isn't realistic. These soldiers and sailors and marines and airmen are so good, and their leadership is so good, that they are doing an enormously complex task the way it should be done. It's different in every part of that country. If [Commanding General] George Casey designed a template and dropped it down and said, 'Here's what each division should do . . . each brigade,' it wouldn't work! Because the situation is different in the north, in the south, in Baghdad. . . . We've got rural problems out west. So what he has to do is get very good people, give them the right kind of leadership, encourage them to be bold and to take risks, and to communicate back what they need, what they're doing, get ideas from others--and go out and do their best, and that's what they do."

So Donald Rumsfeld is not at war. In fact, a postwar feeling pervades Rumsfeld's office, and his focus has returned full-time to leaving a much different Pentagon in his wake. He has told those who need to know that he intends to stay until the end of the second Bush administration, and he's aiming to lock in the big changes he's setting in motion. If he had been around just one term, anyone could have reversed all of this with a few strokes of a pen. Now, well, it will take another Rumsfeld to un-Rumsfeld this Pentagon when he's done and out the door in January 2009.

"Change takes time," he says. "Any CEO in a corporation, you ask him what the rough amount of time to do it, and it's eight or ten years."

Now Rumsfeld is working the "gearbox" issues, as he likes to call them. He's gotten way down into the guts of the Pentagon's machinery, making changes that will redefine how things are planned, how people are employed, how resources are acquired, and how America fights and wins both the wars that lie ahead and the inevitable nation building that must follow. And he aims to make those changes permanent, because "you can get backsliding, but if you go down deep enough in this institution, where nobody notices and nobody sees it and nobody understands it and it's hard to figure out, and you get those things going right, they're going to go on for a long time. Once they're ingrained, they'll go on that way until somebody spends enough time, enough effort, to go in and readjust them down there. But you can't do it superficially along the top. It just doesn't happen."

To go along with all the other ongoing transformation, this gearbox approach of Rumsfeld's is producing two huge philosophical sea changes in the Pentagon that have implications for the entire United States government that will reach across the decades to come.

First, the 2005 Quadrennial Defense Review, to be released in the fall, will shift China from "near-peer competitor" to a rising power whose emergence we need to guide. It also will enshrine the notion that nation building is something the military does, finally reversing the long-standing Powell Doctrine to conform with what's happening in the real world, because dealing with failed states is a fact of life in a global war on terrorism, especially when terrorists seek sanctuary in them.

But perhaps most stunning are Rumsfeld's plans for something he calls the National Security Personnel System, which will radically redefine civilian and military service in the Defense Department, changing from a longevity-based system to a performance-based system. Already, radical new features of this plan have been field-tested in the Navy, where, in the past, so-called detailers told sailors where they were going on their next assignment--with little warning and like it or not. Eager to break that boneheaded tradition, the Navy is experimenting with an eBay-like online auction system in which individual servicemen and -women bid against one another for desired postings. As Admiral Vern Clark told me, "I've learned you can get away with murder if you call it a pilot program."

So Clark is pioneering a system by which, instead of sending people to places they don't want to go on a schedule that plays havoc with their home life, "they're going to negotiate on the Web for jobs. The decision's going to be made by the ship and the guy or gal. You know, we're going to create a whole new world here."

The plan is designed to save the services money and effort by reducing early departures from the ranks by people who just can't take it anymore. The Navy's so-called "slamming" rate, meaning the percentage of job transfers against a person's will, has hovered at 30 to 35 percent in recent years. That means the Navy has been pissing off one third of its personnel on a regular basis. Now, under this program, the slamming rate is down to less than one percent.

More profoundly, Clark's pilot program has already spread to the other services, and in turn could well change the very nature of civil service throughout the United States government.

After considerable time with the top-ranking civilian and military leaders of the Pentagon, a new picture of Donald Rumsfeld has emerged for me, and I now believe something that I would have thought preposterous before: There are no "Rumsfeld wars." Of course, he's integral to how the Pentagon has conducted these operations, and he deserves all the credit and blame any defense secretary naturally receives as a result. But they're not his wars, and they never were. And in that, critics of the war might have something. The rationales behind the Iraq war belonged to the departing neocons Wolfowitz and Feith (who took pains in an interview to lecture me on the correct usage of the word neocon). And of course the president.

Rumsfeld does not seek those badges of war because he does not understand why any SecDef would claim them. He is a technician, not a warrior; a businessman, not an ideologue. He sees his main job as taking care of every single move made up to the first shots being fired. He wants it lighter, faster, simpler, leaner. And he wants that whether or not you give him wars to wage. It just so happens that in his time there have been wars to wage.

The war decisions are somebody else's business. But once you give him those wars to wage, he will use them at will as his proving grounds, sending one force over, bringing another one back. Four armed services existed at the outset of the Rumsfeld era, but only one military force will remain when he's gone.

As the admiral said, if it's a pilot program, you can get away with murder. And the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq have been an astonishing proving ground for Rumsfeld's idea of a transformed Pentagon.

Someone told me this story about Donald Rumsfeld.

Before becoming a public man, Rumsfeld grew up in Illinois, and fifty years ago, he married his high school sweetheart, Joyce. Recently, he told his wife, "I'm concerned that because I've been written about so much, our grandchildren will know all they need to know about me, but they won't know their grandma in the same way." So he decided to write his wife's life story himself in his spare time. So when he has spare time, that's what he does.

The man who told me this was a four-star admiral who got misty-eyed as he sat there talking in his Pentagon office. As a rule, four-star admirals do not get misty-eyed.

But to me, this story says less about the vast unexplored emotional landscape of Donald Rumsfeld and more about a man who simply wants to do things that last.

Back in room 3-E-880, the old man's got a grip-and-grin with a visiting dignitary to see to and has to be on his way. Before he does, though, Rumsfeld emphatically shrugs off the notion that, despite popular perception, he ever gets frustrated. He is, he says, not the frustratable sort. But he does get surprised.

"And the surprise for me is that, I guess the surprise is, in an institution this big--and it is enormous--you can interact with only so many people. And you can provide the energy and the urgency to that universe. If you drop a pebble in a pond, the ripples go out. And the ripples go out from those people. And the test is, how big a stone can you throw in the pond? And how big are the ripples? And how many of them can you do?

"Every once in a while, I find a dead spot that missed the ripples, and I'm amazed! You think, My gosh, you get up at five in the morning, you're in here at six, six-thirty or something, and you're here in the evening, and you work at home, and you're going. . . . All these people are just working their heads off, everyone around me is working their heads off, doing a great job, and then you find a dead spot, and you think, They don't get it! They didn't hear! The ripple never got there! It's a still! It's just a little eddy going around in a circle over there! And you think, Isn't that amazing!? How could they not hear!? What's going on!? And, you know, people want to do the right thing. It isn't that people are resistant to it. Most people want to feel useful; they want to feel they're accomplishing something. So it always surprises me. And then I think to myself, Well, what can we do? How many more of those dead areas are there? The stills, the eddies, where nothing's happening? It's just going around in a circle? And we have to find them. And get after them."

Reader Comments (2)

Thanks for reposting.Fortunate timing. Just finished Graham's "By His Own Rules" and your article pairs nicely with it. Reminded of the line that any strength when taken to excess can become a weakness.

'And transformation was born.

Just as quickly, it almost died.'

Too much of political, academic, media and public did not understand the need for, and nature of the transformation. Those that did saw the likely problems and risks more than they did the opportunities and 'tools.' Difficult conflict situations always always required the good guys to get the bad guys to fight where and when we needed the conflict to be, and in ways that would produce the most favorable results for our side.

Globalization in an era of relatively cheap personal , global communications links, simpler mechanical and chemical methods suitable to GAP folks, and Cold War heritage of US and Russia using Gap folks to undermine each other's global Leviathan strategy, made the new transformation both necessary and difficult at the same time.

Under those conditions our domestic and global political, economic, academic, media and public would have to have insights into the strategies, appropriate tactics, and the need to adapt to local situations and results, so they would feel part of the decision processes. Until 9/11 there was not much positive movement from these groups.

Even now most can just grasp the implication of the last few years, or a decade, on the circumstances they influenced Gap cultures, and they usually got that from a Western educated Gap politician, academic, or emerging business rep. So they did not watch and listen to local folks to get a 'ground up' insight. Even the special opts, military advisors, and worker contractor folks were only given 'simple questions' in discussions with media and politicians.

Most US folks don't understand these Gap cultures emerged and continued over 1000s of years based on their good and bad experiences within their regions, and with periodic Core type outsiders. So let our people on the right shout 'Marco' and our people on the left respond with 'Polo.'

Perhaps someone should look at the difficulty the Core countries have had dealing with Mafia type situations. Even there the differences are significant. New and old worker bears in the Mafia have realistic and rational self-interest orientations. Their bosses are willing to negotiate some rational power and business accommodations with the host societies. For awhile US thought the AK and Taliban were similar, but suicide bombers, and the destruction of social centers and mosques gradually woke us up. Our media still doesn't 'get it' that the friendly folks they interview on TV are risking the lives of friends and their extended family.

And the AK folks really seem how to use our media in their Information War!