NOTE: see "Other Publications/U.S. Naval War College projects"

for PDF version of report

U.S. Naval War College

Center for Naval Warfare Studies

Decision Support Department

Year 2000 International Security Dimension Project Final Report

by

Dr. Thomas P.M. Barnett

with

Prof. Henry D. Kamradt

and based on inputs from

Dr. Lawrence Modisett, Prof. Bradd Hayes, Prof. Theophilos C. Gemelas & Prof. Gregory Hoffman

Originally posted 23 July 1999

TABLE OF CONTENTS

I. Introduction -- Page 3

II. Our Big Picture Approach -- Page 9

III. A Series of Y2K Onset Models -- Page 17

IV. The M Curve of Influence -- Page 33

V. The Scenario Dynamics Grid -- Page 43

VI. Some Preliminary Thinking on CINCs' Strategies -- Page 66

VII. A View From Wall Street -- Page 79

VIII. Some Cosmic Conclusions About Y2K -- Page 94

Appendix Y: List of Workshop Participants -- Page 99

I. Introduction: How This Project Started and Why

The Year 2000 International Security Dimension Project is the brainchild of Vice Admiral Arthur K. Cebrowski, President of the U.S. Naval War College. For those familiar with his career, this should come as no surprise, as he has long served as a leading thinker within the military regarding the intersection of technology and global change. Admiral Cebrowski believes the Year 2000 Problem (hereafter Y2K) can have a significant historical impact on humanity's relationship with technology, if only to rapidly teach us all a great deal about what it means to live in an increasingly interdependent, interconnected, and information technology-driven globalized economy.

Soon after assuming his post at the War College in the summer of 1998, Admiral Cebrowski tasked the Center for Naval Warfare Studies' Decision Support Department, led by Dr. Lawrence Modisett, to engage in a year-long study of Y2K's potential to trigger significant scenarios of internal or transnational instability in the world outside the United States.

We've since defined "significant scenarios" to mean a crisis situation of significant magnitude to demand--under the potentially unprecedented global circumstances of Y2K--Defense Department (DoD) attention in terms of possible crisis response. Such a response could range from anything as minor as the rapid insertion of a small "tiger team" to help foreign nationals repair a specific network facility to something on the order of a Complex Humanitarian Emergency mission to some country or region especially hard hit. In short, it's a wide open playing field, with a key uncertainty being how the United States itself weathers the Y2K Event.

From the beginning of this project, we've stressed an "agnostic" approach on Y2K and its potential impact, meaning we seek neither to rally a broad social or governmental response to deal with this problem (e.g., the ongoing remediation effort) nor to present any sort of "official" government outlook on what is likely to happen. Instead, we've approached the Y2K event as we would any other potentially destabilizing event of serious political-military impact--by employing a standard decision scenario approach. By "decision scenario approach," we mean using credible scenarios to create awareness among relevant decision-makers regarding the sort of strategic issues and choices they are likely to face if the more stressing pathways envisioned come to pass. Naturally, because we work for the military, we're more interested in the "darker" scenarios. That doesn't mean we expect or predict really bad things will happen, only that we think it's essential the U.S. Military must consider the potential scope of the problem in advance so as to avoid both errors of omission and comission once the Y2K Event begins--with an emphasis on the latter.

How We View the "Whole Enchilada"

As you'll notice, we call our project the Year 2000 International Security Dimension Project--not the Y2K International Security Dimension Project. Why? It's our firm contention that DoD should view the Millennial Date Change Event as comprising a constellation of simultaneously unfolding elements, of which Y2K is clearly the most important. Our draft list of globally significant pieces to this puzzle would begin as follows:

- Year 2000 computer problem (e.g., software and embedded chips) in and of itself

- Y2K--the global remediation effort and all that it entails

- Y2K as a global education process regarding the pervasiveness of "all this invisible technology"

- Y2K as a global crisis management challenge and economic threat

- Global economy just coming off a period of significant widespread turmoil (e.g., the Asian Financial Crisis of 1997 and its subsequent spread to Russia and Brazil), resulting in significant reform efforts by many of the affected countries

- Millennial Event in its largely secular form, i.e., the "world's largest party ever"

- Millennial Event in its religious form, i.e., celebrating the onset of the Third Millennium since Christ's birth

- Millennial Event in its socio-political form, i.e., marking a milestone period in the planet's history during which political leaders, as well as ordinary citizens, engage in extraordinary debate regarding the status quo and what should logically follow

- Millennial Event is its extremist form, i.e., the strong assumption by some in society that the event will usher in profound and cataclysmic global change, typically associated with apocalytic visions involving a deity or supernatural force

- Tendency of humans to seek grand unifying theories for periods of human history that involve above-average levels of complexity, and utilize those theories as guides for self-perceived "strategic" action.

Looking at that list, you quickly come to the conclusion, as we did last fall, that this was not a subject one could handle in the typical BOGGSAT-style (Bunch Of Guys & Gals Sitting Around a Table). No, we needed many bunches of guys and gals sitting around many tables, parsing out this huge puzzle from a variety of perspectives. Since the Decision Support Department's greatest expertise comes in talking with experts and synthesizing their views for wider distribution, we soon settled on a workshop approach that would involve a very broad range of expertise outside the military. [A complete list of our workshop participants can be found in Appendix Y.]

Looking over that list, we likewise came to the conclusion that, since the Millennial Date Change Event appears to have so much "baggage" and "fellow travelers," so to speak, our project risked expanding into a study about anything happening to anyone anywhere in the world come 1 January 2000. While not shying from that challenge, for you'll see that comprehensiveness is our calling card, we readily realized that ours would not be a technical approach of lists upon lists of things that could go wrong. Rather, we decided that the most feasible approach for a small research unit such as ours would be to concentrate on the broad dynamics of the possible scenarios, to include not only the functioning of networks (broadly defined as any distributed system that moves material), but economic activity, societal responses, as well as the operations of government entities.

In a nutshell, then, our project became focused--despite the broad nature of the subject matter--on the possible scenario dynamics the Defense Department could face if it were tasked by the national leadership to engage in crisis response activities abroad during the Millennial Date Change Event and the subsequent unfolding of the Y2K Event. Mind you, our assumption going in was that we would not uncover any new or unprecedented missions for the CINCs (Commanders in Chief) of DoD's various regional military commands (e.g., Southern Command covering Latin America, Central Command covering SouthWest Asia, European Command covering Europe and most of Africa, and Pacific Command covering most of Asia in addition to the Pacific island states)--and, to date, we have not found any. Rather, our assumption has been all along that, while the CINCs are likely to engage in very familiar missions of crisis response, it is the internal or regional dynamics into which they may delve that will be unusual and worth preparing for in advance.

The Structure and Schedule of the Workshops

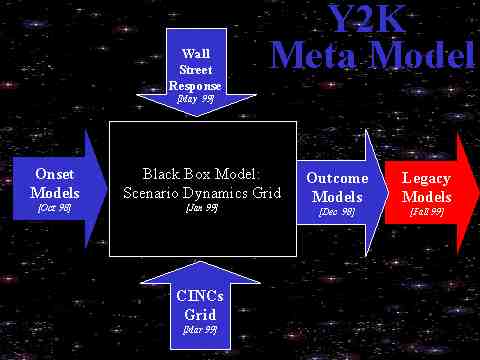

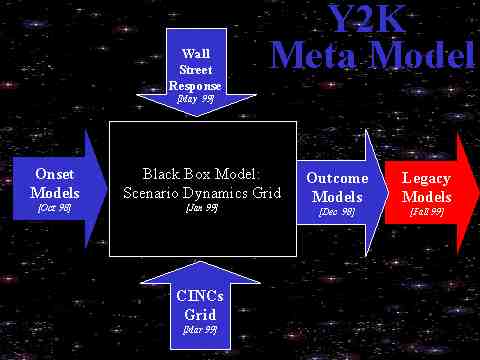

We conducted four workshops, starting in December 1998 and concluding in May 1999.

DECEMBER SCENARIO-BUILDING WORKSHOP

For our first workshop in December of last year, we invited about two dozen functional experts to help us construct and flesh out a series of generic onset models (presented later). The experts invited fell into four rough categories of knowledge and experience:

- Distribution/Service Networks (e.g., food, basic needs, oil/gasoline, air and mass transit, electric power, and telecom service)

- Business activity (e.g., major manufacturing, major retail, medical, insurance, and finance-banking)

- "Social communications" (e.g., mass media, government regulation of mass media, face-to-face and individual comms, the Internet)

- Government services (e.g., defense, police, basic services, and emergency services).

Visit our archive website (http://www.nwc.navy.mil/y2k) to view the readahead package for the December Scenario-Building workshop held at the Decision Support Center of Sims Hall at the U.S. Naval War College in Newport, RI.

The participants at this event provided us with a number of useful and imaginative inputs via a meeting facilitation software program known as GroupSystems (e.g., scenario pieces presented in the format of "newspaper headlines," possible warning indicators of events moving from one scenario to another, "bumper sticker" names for individual scenarios), in addition to their moderated participation in nine separate discussion sessions covering the following topics:

- Y2K as a series of discrete and periodic events

- Y2K as a widespread and sustained event

- What makes a country’s "networks" (broadly defined to include social networks) robust?

- What makes them vulnerable?

- Signposts indicating the nature of the Y2K event’s unfolding

- The best-case scenario (Y2K as discrete/periodic and systems are robust)

- The next-best-case scenario (Y2K as sustained/widespread and systems are robust)

- The next-worst-case scenario (Y2K as discrete/periodic and systems are vulnerable)

- The worst-case scenario (Y2K as sustained/widespread and systems are vulnerable)

- "You Make the Call!" on Y2K both within the US and around the world.

We were able to gather and edit several hundred ideas and scenario vignettes from the various GroupSystems sessions and subsequently published them on our web sites at the Naval War College and Geocities. Visit our archive website (http://www.nwc.navy.mil/y2k) to view the GroupSystems inputs from this workshop.

JANUARY SCENARIO-DYNAMICS WORKSHOP

At our second workshop in January of this year, we brought together about two dozen functional experts with a strong experience/knowledge base in networks, business activity, social issues and/or government in one of five world regions:

- Western Hemisphere outside of US

- Europe (to include Russia)

- Southwest Asia (to include Middle East, Central Asia, and Indian sub-continent)

- Asia

- Africa.

Visit our archive website (http://www.nwc.navy.mil/y2k) to view the readahead package for the January Scenario-Dynamics workshop held at the Senator Claiborne Pell Center of Salve Regina University in Newport, RI.

Participants at this event provided the study team with a number of useful and imaginative inputs via the GroupSystems approach (e.g., advice-filled "e-mails" written to their "close personal friend" who serves as top policy adviser to the President of Country X), in addition to their moderated participation in eight separate discussion sessions covering the following topics:

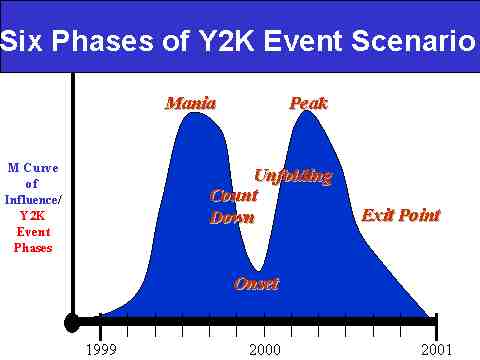

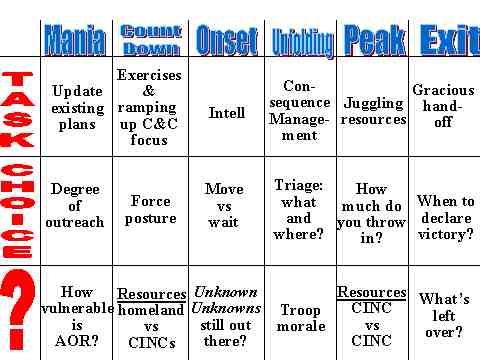

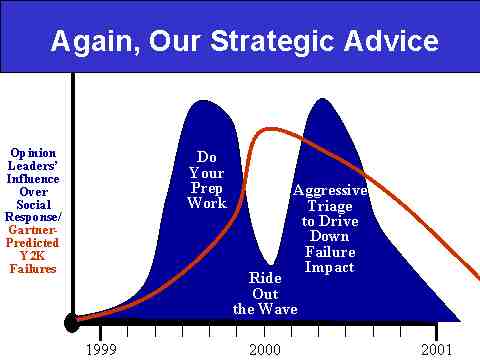

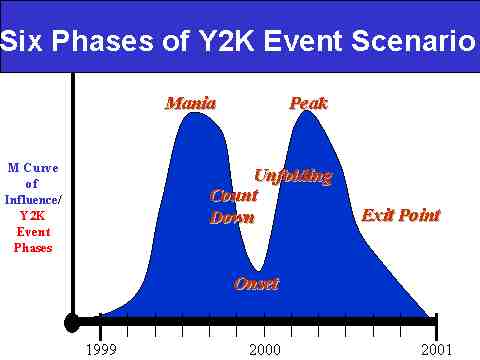

- "Mania" phase of the Y2K event (see the section, The M Curve of Influence for details)

- "Countdown" phase

- "Onset" phase

- "Unfolding" phase

- "Peak" phase

- "Exit" phase

- Possible malevolent acts by those seeking to destabilize social order

- Region-by-region predictions as to how Y2K will impact nation-states.

We were able to gather and edit several hundred ideas and scenario vignettes from the various GroupSystems sessions and subsequently published them on our web sites. Visit our archive website (http://www.nwc.navy.mil/y2k) to view the GroupSystems inputs from this workshop.

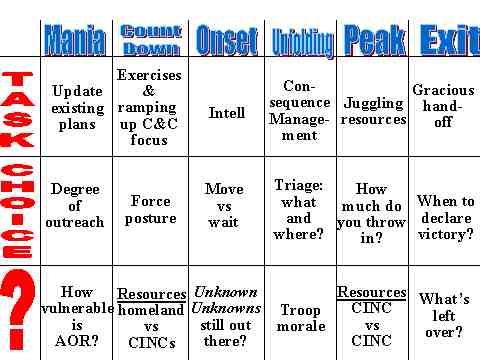

MARCH SCENARIO-STRATEGIES WORKSHOP

At our third workshop in March, we explored the possible range of DoD policy measures and associated CINC regional strategies that might be pursued in response to the unfolding of the Y2K and associated Millennial Date Change Events along the phased scenario timeline developed and populated in the January workshop. While we benefited by some CINC representation, our real focus was on tapping into the extant inside-the-Beltway knowledge base regarding Y2K contingency planning, with an eye toward blending that knowledge with our own for eventual provision to the individual CINCs as both they and the Joint Staff begin planning against the threat of Y2K-induced crises around the world. The participants at this workshop came mainly from defense-related federal agencies and think tanks.

Visit our archive website (http://www.nwc.navy.mil/y2k) to view the readahead package for the March Scenario-Strategies workshop held at the headquarters of The CNA Corporation in Alexandria, VA.

Participants at this event provided the study team with a number of interesting and illuminating inputs via the GroupSystems approach, which in this instance involved providing us feedback on our proposed list of "policy do's and don'ts" for the governing authorities of a notional country as well as our list of possible CINC mission categories (see the readahead package for details). For purposes of the one-day workshop, we reduced our six-phase scenario timeline to the following three groupings (which formed the basis for our three discussion sections):

- "Mania/Countdown" phases

- "Onset/Unfolding" phases

- "Peak/Exit" phases.

We were able to gather and edit several dozen ideas and commentaries from the various GroupSystems sessions and subsequently published them on our web sites. Visit our archive website (http://www.nwc.navy.mil/y2k) to view the GroupSystems inputs from this workshop.

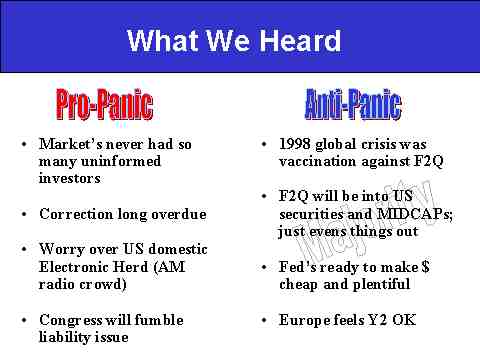

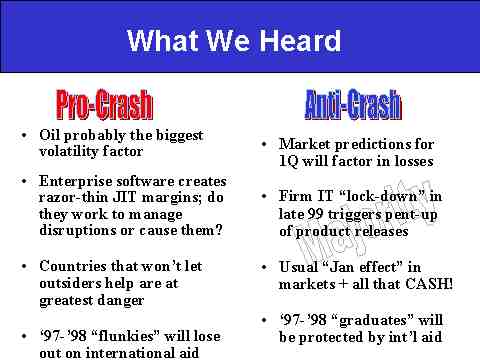

MAY ECONOMIC SECURITY WORKSHOP

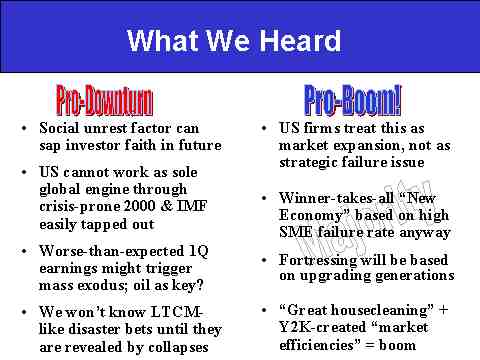

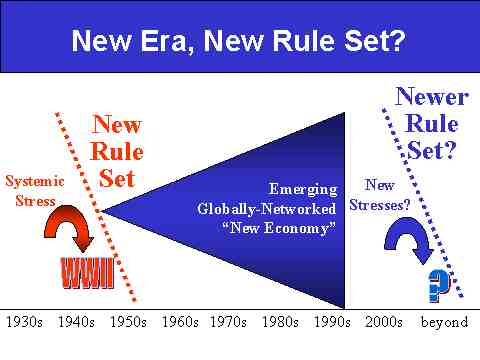

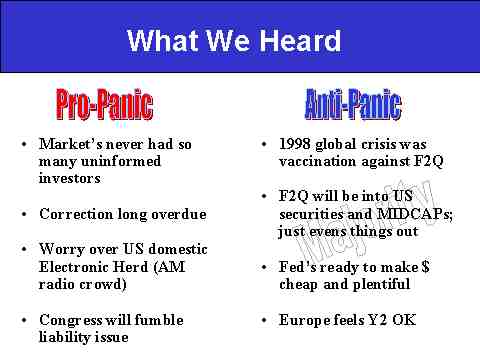

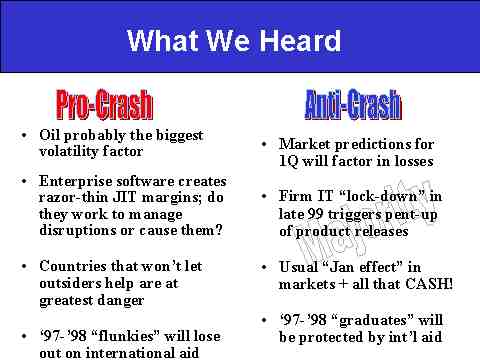

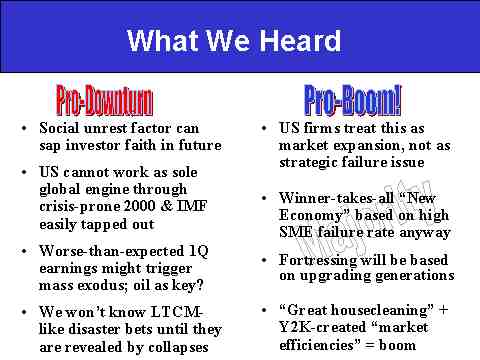

At our fourth and final workshop in May, we focused on how global financial markets would "process" and/or be impacted by the Y2K event. Most specifically, we were interested in exploring how Y2K could trigger a "new rule set" for the international economy by further crystalizing some of the most pressing issues arising from the Global Financial Crisis of 1997-98 (e.g., push for more controls over international capital flows, calls to revamp/reform the IMF, more transparency in Emerging Markets and Hedge Funds, de facto dollarization of some economies). The participants at this workshop came from a variety of Wall Street investment banks, brokerage firms, and related financial organizations.

Visit our archive website (http://www.nwc.navy.mil/y2k) to view the readahead package for the May Economic Security workshop hosted by Cantor Fitzgerald LP in the World Trade Center in Manhattan, New York.

Participants at this event provided the study team with a number of interesting and illuminating inputs via the GroupSystems approach, which in this instance involved providing us with arguments--both pro and con--as to Y2K's potentially negative impact--both short and long term--on global financial markets across the same three scenario-phase pairings employed in the March workshop.

We were able to gather and edit several dozen ideas and commentaries from the various GroupSystems sessions and subsequently published them on our web sites. Visit our archive website (http://www.nwc.navy.mil/y2k) to view the GroupSystems inputs from this workshop.

Some Caveats Before Proceeding

Understanding that there is a tremendous gap between the public face many corporations and governments put forward on this issue ("we will have it well in hand") and the private fears and concerns expressed by many information technology experts (ranging from "global recession" to "apocalypse 2000!"), we wanted to explore this topic in as systematic a fashion as possible. We've never pretended that we'll end up with all the answers, but merely a sensible read on what's possible, how governments and companies are likely to respond across a range of scenarios, and what the USG and DoD should be prepared to undertake in response to Y2K's global unfolding. In short, while we're not interested in unduly hyping the Y2K situation, we are interested in exploring the "dark side" potentials because, frankly, that's what we get paid to do as a research organization that serves the U.S. military.

So read on, understanding that all our "what-if?-ing" serves neither as prediction nor perception management by the U.S. Naval War College. Like everyone else on this planet studying Y2K, we're groping for answers. Yes, we've done our effort in a rather comprehensive fashion, and yes, we are experts at thinking about future events. But please don't approach this analysis as "cookbook," but rather as "primer." The confidence we seek to instill in readers--key decision-makers and average citizens alike--is one of comprehending the potential scope and complexity of the scenario, and not of reducing the Millennial Date Change Event into a crude or simplistic "one-to-ten scale" type of crisis management strategy.

There's nothing wrong with being deeply concerned about Y2K on a global scale after you've read our report, but if you're fearful or panicked, then you haven't really understood what we said.

II. Our Big Picture Approach

DoD Preparations for Y2K and Where We Fit In

We won't be offering any "official history" here, nor any insider critiques of US Government efforts to prepare for Y2K. We just want to be up front and clear in explaining how we see our work fitting in with the rest of DoD's broad, long-term effort that stretches back several years. By and large, we're late-comers to this party, having only begun our research effort in August of 1998. To the extent that we've moved closer to the head of the pack on scenario planning, it's because we've focused on the broad dynamics of how the Millennial Date Change Event may possible unfold--not on the technical aspects of network, software, or embedded chip failures directly caused by Y2K, nor on any remediation efforts to prevent such failures. In short, we're pure crisis management in focus, which is why our analysis has attracted particular attention within the intelligence community.

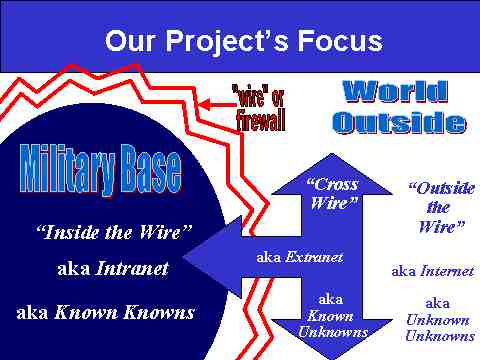

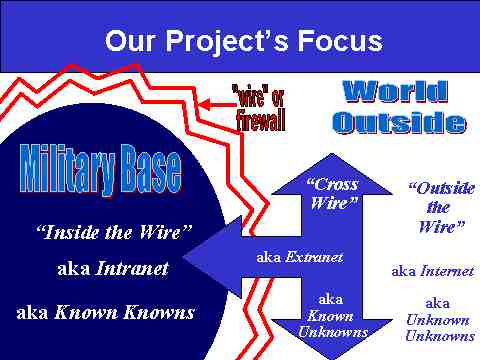

Slide 1: Inside the Wire vs. Cross Wire vs. Outside the Wire Perspectives

Slide 1: Inside the Wire vs. Cross Wire vs. Outside the Wire Perspectives

DoD preparations for Y2K through the spring of 1999 have almost exclusively focused on dealing with what we'd describe as the known knowns (see Slide 1 above), or identified problems that have identified answers. For DoD, it's useful to think of these problems--albeit in a highly reductionist manner--as those that occur inside the wire ("wire" referring to that which separates the military world from the civilian world, or the fences that typically surround military bases), meaning those activities that occur within bases or between operating platforms (e.g., ships, planes, transport vehicles). This is the classic remediation focus one would expect: making sure all our systems work individually and collectively. By most reasonable measures, DoD has this problem set well in hand--and it only makes sense that it would. It's a huge organization with lots of money and lots of responsibility.

Starting early this year, DoD attention has turned increasingly to the subject of host nation and US local community support to military bases--namely, utilities such as electricity, phone systems, and sewer. We like to describe this set of potential issues as the known unknowns, meaning identified problems without easily identified answers. If the known knowns can be thought of as existing inside the wire, then the known unknowns are basically those Y2K issue areas that cross the wire that separates the military and civilian worlds. From DoD's perspective, no matter how well they remediate their own systems and networks, there's still the huge question of how much their base operations rely on host nation support. This will be a subject of intense DoD effort and planning as the rest of the year unfolds.

Our project's work really has nothing to do with either of those first two problem sets, for what we're really concerned with is what can still go wrong beyond the wire. Moreover, we're not concerned with bases located within the US, as Y2K crisis management within the US will be led by the Federal Emergency Management Agency in conjunction with a host of state and local government agencies. Thus, our study's focus is exclusively on what could go wrong during Y2K beyond the wire in foreign countries, or crises to which DoD could be called upon by National Command Authority (i.e., the White House) to respond. This is the real set of unknown unknowns, for while most Y2K analysts will agree that we have a fairly decent read on what will or will not likely happen in the US, our sense of what could or could not go wrong abroad is far weaker.

Historically, the US responds to about 5 to 8 major crises a year around the world with some sort of significant military effort (e.g., ships dispatched, troops deployed, planes fly sorties). Typically, 2 to 3 of these crises are ongoing situations where we continue operations begun in a previous year, like those today in the Former Republic of Yugoslavia or Iraq. The rest tend to be "peaks in messes," meaning ongoing bad situations that flare up or deteriorate to the point that the US decides to intervene militarily in some manner, such as recent forays into Haiti or Somalia.

Of course, the $64,000 question with Y2K and the Millennial Date Change Event is, "Is this confluence of elements likely to create a higher-than-normal crisis load for DoD over the year 2000?" For example, instead of looking out on the world and seeing the usual 10 to 20 crises and picking 5 to 8 for response, does the US Government look out over the course of 2000 and see some larger number of crises, and, if so, do we pick the same "top 5 to 8?" Or a different "top 5 to 8?" (meaning our calculus of national interest might be changed during this unusual period). Or do we try to do more than the usual effort? In short, how important may Y2K turn out to be in terms of US foreign policy--both in the short term and over the longer term?

No one can offer precise answers to these questions. What we can say, though, is that our analysis to date hasn't uncovered any serious evidence that what DoD could be called upon to do in terms of crisis response would be dramatically different from what we've done in the past--namely, disaster relief and humanitarian assistance. Of course, there's always the chance that crisis will generate conflict, but again, we don't foresee any new species of crisis here, but rather the types of situations with which DoD has great experience.

We believe our analysis offers particular utility in alerting military planners, decision makers, and operational commanders to the sorts of broad scenario dynamics they may encounter if they are called upon to engage in military operations in response to Y2K-related crises, or even non-Y2K-related crises that occur during the same time period. So while the missions may not change, the local and regional environment within which those missions occur may experience social, political, economic and infrastructural dynamics that are unusual and linked to either Y2K or the larger Millennial Date Change Event. Moreover, to whatever extent our analysis of generic Y2K and Millennial Date Change Event scenario dynamics illuminates potentially similar dynamics within the US, additional understanding may accrue concerning the overall stress level that may occur "back at the home front."

Again, none of our material here is meant to be predictive in the sense of providing a step-by-step "cookbook" approach to Y2K and Millennial Date Change crisis management. Our fundamental goal in collecting and synthesizing this analysis is to avoid any situation where US military decision makers and/or operational commanders would find themselves in seemingly uncharted territory and declare, "I had no idea . . .." We can't and won't tell any regional CINC staff how to run a military operation during Y2K's unfolding or the Millennial Date Change Event. They know far better than we how to proceed in such real world contingencies. All we can do is alert them to the particular scenario dynamics that may come together during this potentially unusual global experience.

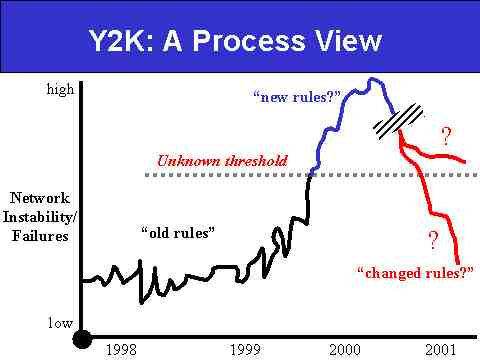

A Process View of Y2K

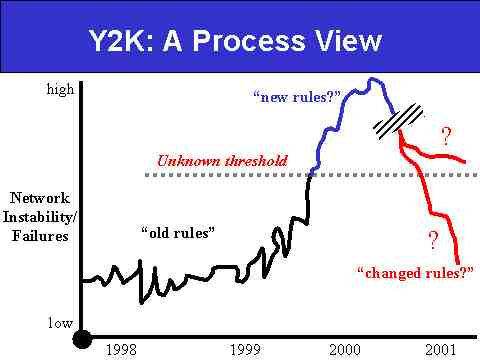

"Y2K--The Event" will feature a distinct build-up phase (already begun), a peak period we consider "THE crisis," and an "end" phase in which the crisis unwinds either by its own accord or, more likely, by decree. Either governments will declare that the "crisis has passed" or some other crisis will arise and capture our attention. Slide 2 below presents another way of thinking through the process of Y2K's build-up, unfolding, and end.

Slide 2: A Process View of Y2K

Slide 2: A Process View of Y2K

The vertical axis of Slide 2 speaks to Network Instability/Failures, meaning the sorts of computer and network failures we've all experienced in our daily lives. The horizontal axis offers a timeline from 1998 to 2001.

As we move from left to right, the relatively low level of network instability and/or failures that we show for 1998 represents life as we know it--i.e., computers and networks break down with a certain frequency that we have come to know and accept. A big part of that acceptance is the "rule set" we have developed for dealing with these failures, such as "Always check by phone if the pager seems down," or "Always follow up with a phone call when the e-mail doesn't seem to go through." We'll call these familiar rules of thumb the "old rules," which we've developed as workarounds for familiar failures. These are our effective coping mechanisms, to use a psychological term.

The key uncertainty for 1999 is the extent to which the level of network instability/failures begins to rise over the course of the year as we get closer to dateline 010100 (six digit code representing the first day of January, 2000, as in, ddmmyy). If Y2K turns out to be a significant experience, then at some point in late 1999 or perhaps the first few days of 2000 the frequency and/or severity of the network instability and/or failures will reach some unknown threshold past which the "old rules" will no longer seem to apply. At that point, society would--in effect--develop a "new rule set," or "new rules" that apply to the dramatically altered parameters of the perceived crisis situation--however defined.

Our project is largely concerned with uncovering and understanding the potential "new rule set" that would ensue if Y2K, when combined with the Millennial Date Change Event, turns out to cause a significant and unprecedented rise in network instability for an extended period of time. Now, we can debate what the word "extended" means, but for our analytical purposes, it would be a length of time that exceeds what a reasonable citizen might expect in terms of network, economic, social, and government service disruptions arising from the "3-day snowstorm" measure that many advocate as a planning parameter for Y2K. Any unfolding of Y2K that doesn't create a lengthier array of significant disruptions for any area, country, or region, is unlikely to generate a "new rule set."

Finally, once the Y2K Event plays itself out (signified in the slide by the break in the chart line) and the failure/instability rate begins to decline, the question in terms of Y2K's long-term legacy is whether or not we return to the "old rules" associated with the previously understood standard of network instability, or whether we settle in on some "changed rule set" engendered by our experiencing of the Y2K Event. In large part, that will depend on the extent to which we come to understand Y2K as either a one-time event unique in human history or a preview of what "network instability" (and its associated crises) may evolve into as we move ever deeper into a period of history where individuals, communities, countries, and regions of the world become more interconnected and interdependent. In short, if globalization and networking represent the future, maybe Y2K has far more to teach us about that future than we might think if we view it as nothing more than the "last stupid act of the 20th Century."

Millennial Mania as a Key Element of the Millennial Date Change Event

In this section, we'll define Millennial Mania as corresponding to one of our previously noted elements of the Millennial Date Change Event--namely, the Millennial Event in its extremist form, i.e., characterized by expectations of profound and cataclysmic global change, typically associated with apocalyptic visions involving interventions by a deity or supernatural force. Having to define this element, we might seem to be relegating it to the extreme edges of society, and, to a certain extent, we are.

However, given the simultaneity of Y2K's unfolding and the opportunity afforded by the Millennial Date Change Event for a portion of the public to interpret Y2K's meaning and causality through the prism of an apocalyptic perspective, the Millennial Mania element may--in effect--"pour fuel on the fire," heightening inappropriate or counter-productive responses to those direct Y2K failures that may occur. This can happen in a variety of ways, with the three most important avenues being:

- Tendency to extrapolate direct Y2K failures into "overwhelming evidence" of the collapse of society

- Propensity to attribute causality of "fellow traveler" failures to Y2K, thus feeding the "overwhelming evidence" of the collapse of society

- Capacity to behave in response to such "overwhelming evidence" in ways that, in turn, lead to cascading network failures or related societal breakdowns where none would have otherwise occurred, which subsequently provide even more "overwhelming evidence" in a self-fulfilling fashion.

It is the last concept that we would like to highlight--namely, the notion of "iatrogenesis," which is narrowly defined as the unintended side effects resulting from treatment by a physician, but which we use more broadly to mean average people doing stupid things during stressful times (although the notion of unintended side effects caused by a true expert is useful as well--namely, the mistakes created by software remediation).

As is readily apparent to anyone who's tracked the Y2K debate, there are many Y2K "physicians" currently on the scene, many of whom have little understanding of information technology, but who are nonetheless offering all sorts of "advice"--usually for a fee. By and large, we are not talking about IT firms and consultants in the business of remediation or commercial crisis management, but the relatively narrow group of self-proclaimed experts who offer frightening predictions regarding Y2K effects, as well as ways to "weather the storm"--usually by purchasing their products or services.

In addition to the hucksters and outright scam artists, there is a relatively small but highly vocal and well connected (over the Internet) group of individuals and organizations promoting all sorts of apocalyptic interpretations of Y2K's meaning and causality. Some seek remuneration, but many do not, as they firmly believe--in their millennarian fashion--that the "signs" of the "end times" are somehow foretold in Y2K's onset and unfolding. The vast majority of these "physicians" tend to predict great harm will come to those elements of society for whom they have historically shown great contempt. In other words, these "experts" tend to warn of disaster for those unlike themselves, with "unlike" being defined in terms of religious beliefs, racial or ethnic categories, political attitudes, social mores, sexual orientation, and the like. The tendency of some of these "experts" to attribute Y2K's alleged destructiveness to the "evilness of their ways" is unmistakable and deplorable.

Such fear-mongering "physicians" prey on those intimidated by information technology in general, and in particular those looking for external guides to help them interpret and understand Y2K's meaning and causality. The impact this small but influential group of "experts" may have on societal response to Y2K's onset and unfolding is extremely difficult to predict. Mass media and elites in general tend to grossly overestimate the panic factor in natural and man-made disasters, as proven time and time again throughout history. Moreover, the tendency of elites to censor the flow of information out of fear of panic is often a far larger source of instability than the crisis itself. In that sense, it is less the power over mass behavior that fear-mongering "physicians" or "experts" actually exert during Y2K's onset and unfolding, than the power they seem to exhibit in the preceding months and weeks that may negatively impact elite decision making regarding the transparency of government preparations and plans for dealing with whatever crisis may actually ensue. In short, the most profound iatrogenic effect these "physicians" or "experts" may have could be on elite behavior vice mass behavior--again, in that self-fulfilling manner that exemplifies iatrogenesis.

For further insights into Millennial Mania and the forms it may take surrounding Y2K and the Millennial Date Change Event, we recommend the following:

- Visit Boston University's Center for Millennial Studies' web site (www.mille.org) for more information regarding millennarian or apocalyptic groups and their potential for disruptive or iatrogenic behavior in the coming months; the site provides many good links in addition to numerous interesting and illuminating interpretations of ongoing social response to both Y2K and the Millennial Date Change Event

- Rent any of the following movie videos for glimpses into a variety of extreme responses or emotional dynamics that segments of society may exhibit during Y2K and/or the Millennial Date Change Event:

- The Rapture (1991), on why certain people are attracted to visions of religious-based apocalypse

- The Trigger Effect (1996), on how stressful situations can lead to iatrogenic behavior due to "battle fatigue"

- The X-Files (1998), on "paranoia" (you can figure out your own definition of that word) over government conspiracies, cover-ups and the abuse of political power during crises

- Deep Impact (1998), on divided loyalties in the face of looming crisis and popular responses to the notion of "The End of the World As We Know It (aka, "TEOTWAWKI," a broad theme that runs through much of the apocalyptic interpretations of Y2K's potential global impact).

And if none of that jars your imagination regarding Millennial Mania, then just consider that astronomers are predicting one of the most violent periods of solar flare activity in recorded history for the period January through March 2000. So, if you're looking for a sign from above . . . you'll get it.

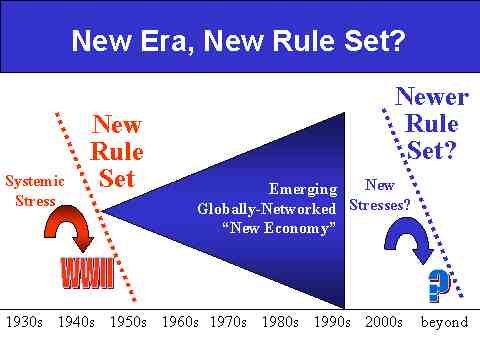

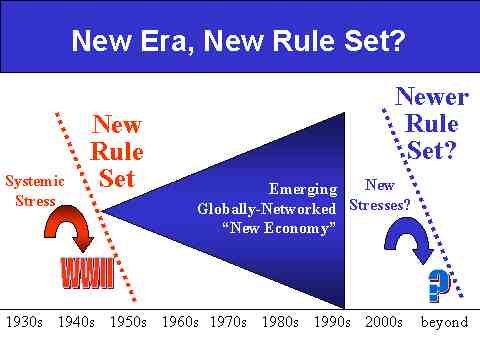

The Biggest Picture View of Y2K's Potential Impact on Global History

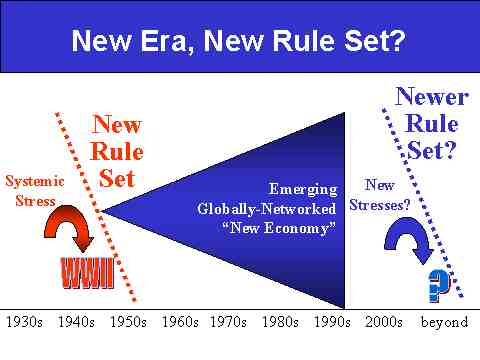

The Y2K Event comes at what may be a pivotal point in global history. We'll explain this bold statement using Slide 3 below:

Slide 3: The Biggest Picture View of Y2K

Slide 3: The Biggest Picture View of Y2K

The global rule set that has marked international relations throughout the Cold War period and into the 1990s finds its roots in the systemic stresses of the 1930s--namely, the Great Depression and the rise of fascism in Europe. These twin developments relatively quickly segued into the Second World War, from which came the notion that "never again" would the international community engage in the sort of self-destructive behavior (e.g., economic protectionism) that both led to and exacerbated the Great Depression, and by doing so laid much of the groundwork for World War II. Based on that "never again" spirit, the global system's great powers, led most notably by the United States, attempted to "firewall off" the experiences of the 1930s and early 1940s by creating a new global rule set, whose main attributes were exemplified by such international organizations as the General Agreement on Trade and Tariffs, the United Nations, the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank.

This new global rule set gave birth to the second great period of economic globalization (the first being roughly from 1880 to 1929), creating what we've eventually come to know and identify as the globally networked "New Economy." This New Economy features, as Thomas Friedman has noted in his book, The Lexus and the Olive Tree (New York: Farrar Straus Giroux, 1999, pp. 39-58), three critical democratizing processes:

- Democratization of global finance

- Democratization of global communications

- Democratization of global technology.

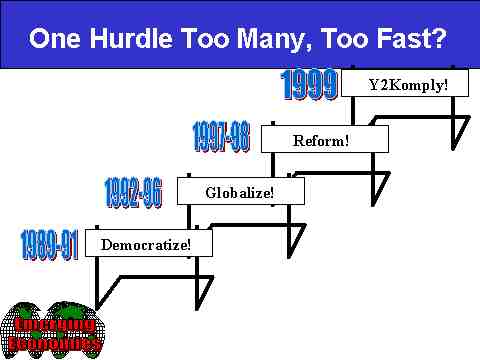

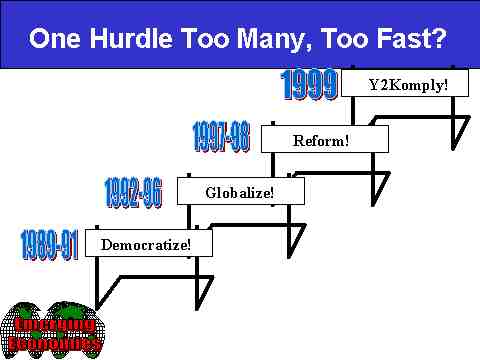

As this New Economy emerges on a global scale, it has begun to feel some "growing pains," most notably in the global financial crisis of 1997-98 (beginning in Asia and spreading to Russia and Brazil), leading some to question whether the Global Rule Set of the early postwar years is still appropriate for the world in which we currently live. Granted, the now seemingly "old" Global Rule Set of the late 1940s and early 1950s succeeded beyond the wildest dreams of its progenitors. It not only outlasted the main threat to global stability of its time, the Soviet Bloc, but created the greatest period of global economic advance in history, not to mention the longest period of great power peace in the 20th Century. However, as states and their economies become increasingly intertwined in this information technology-driven New Economy, legitimate questions arise as to whether or not a new Global Rule Set is in order.

Naturally, the United States is not particularly enamored with the call for a new Global Rule Set, for it is doing quite nicely in the current set and most of the calls for new rules typically center on placing restrictions on the free flow of international capital, something the U.S. does not wish to see for reasons of its obvious economic success over the course of the 1990s. If, however, Y2K were to induce serious global economic disruptions, coming as it does on the heels of the Global Financial Crisis of 1997-98, then it is possible that international sentiment for some aspects of a new Global Rule Set, however defined, would grow so powerful that even the United States might find it advantageous to shape its emergence rather than delay or prevent its emergence.

Could Y2K play the role of the "straw that breaks the camel's back?" At this point, it seems like a long shot, and yet, 1989 looked to be a rather ordinary year until 1990 rolled around and we realized the Cold War was essentially over. In short, we rarely have the opportunity to schedule moments of global historical importance--they simply appear on their own and usually elicit our great surprise. The fact that Y2K is indeed a scheduled moment in history only adds to its mystery, but in the end, if Y2K proves to be an historical turning point between one era and the next, it won't be because of what Y2K is, but because of what it told us about the status quo and the need for change. In short, it's not what Y2K destroys that will be important, but what it illuminates.

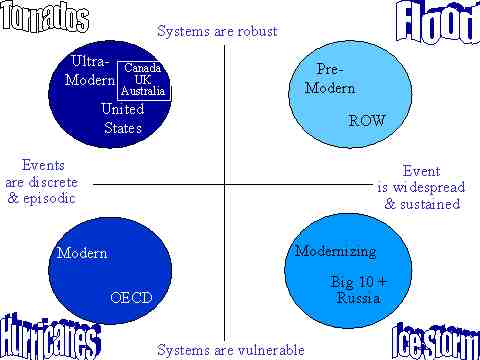

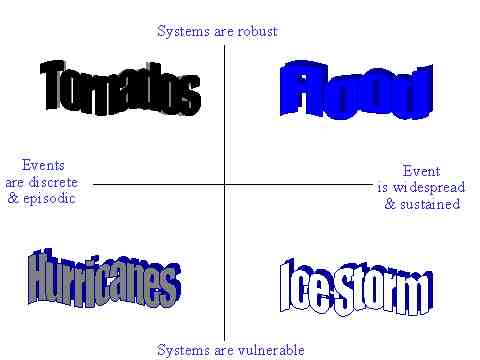

III. A Series of Y2K Onset Models

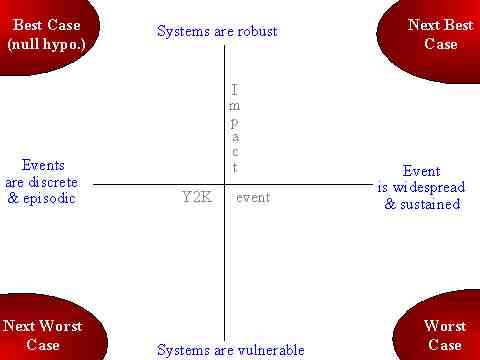

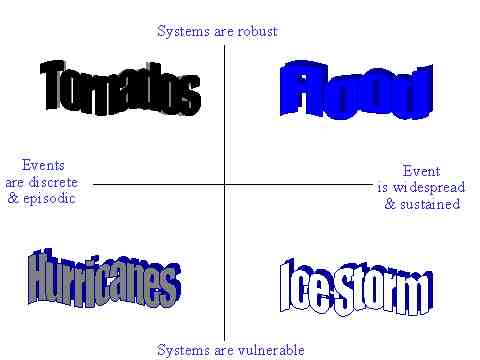

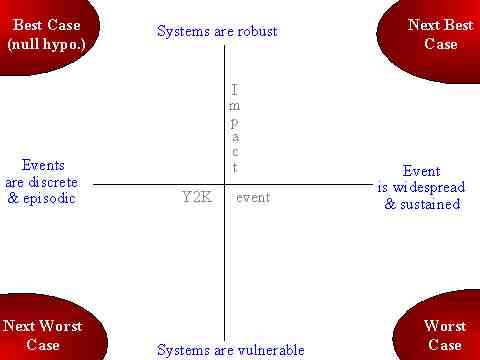

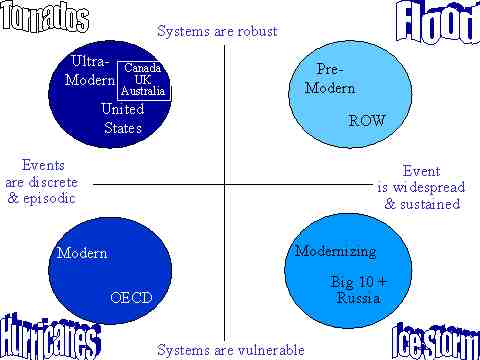

Explaining Our X-Y Axis

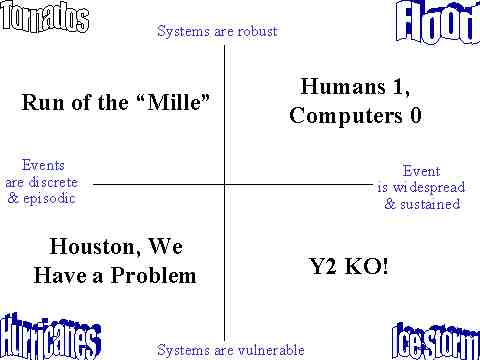

Our X-Y Axis (shown below as Slide 4) begins with two simple questions:

- Horizontal axis asks the "What?" question: What is the nature of the Y2K Event?

- Vertical axis asks the "So What?" question: What is the impact of the Y2K Event?

There is a huge difference between these two questions, for the first question focuses on cause, while the latter focuses on effect.

One way we like to differentiate between the two questions is to employ a medical analogy. Think of the horizontal axis (What? question) as the nature of the trauma or illness and the vertical axis ("So What? question) as the patient's overall health. Two extreme examples show why this analogy is illuminating:

- Example 1 is an elderly man who is stricken with a very slow growing bladder cancer. While this elderly man could have lived with this cancer for several years, the stress of his hospitalization, exploratory surgery, and the frightening diagnosis stresses his already fragile system to the point where he suffers a stroke and is dead within two weeks as a result of major organ failures cascading throughout his system. To sum up, while the initiating event (bladder cancer) was more minor than major (placing it on the left side of the horizontal access below), the man's overall system robustness was weak (placing him on the lower side of the vertical axis). The medical outcome was--irrespective of its modest origins--disastrous.

- Example 2 is a two-year-old child struck with a very aggressive kidney cancer that--by the time of diagnosis--has spread to both her lungs. Other than that, though, the child is in excellent health, and as such, is more than able to survive the surgeries, radiation, and months of chemotherapy with no lasting negative effects of clinical value. To sum up the child's case, while the initiating event (kidney cancer) was more major than minor (placing it on the right side of the horizontal axis), the child's overall system robustness was strong (placing her on the higher side of the vertical axis). The medical outcome was--again, irrespective of its profound origins--quite positive.

These two very different medical case histories, drawn from the author's family history, highlight the importance of juxtaposing the "What?" and "So What?" questions to create the four quadrants of the X-Y axis, for it is not enough simply to ask how bad Y2K may be. Given how bad it may be (i.e., how many computerized systems fail), Y2K's ultimate impact will depend greatly on the targeted system(s) in question.

Looking at Slide 4, we then explain our X-Y Axis as follows:

- The horizontal axis, asking the "What?" question of the Y2K Event, posits the minor extreme on the left as being "Y2K events are discrete and episodic" and the major extreme on the right as being "Y2K event is widespread and sustained."

- The vertical axis, asking the "So What?" question of Y2K's impact, posits the minor extreme on top as being "Systems are robust," and the major extreme on the bottom as being "Systems are vulnerable."

Two caveats are in order:

- By "Y2K Event(s)," we refer only to network failures directly attributed to Y2K or those caused via subsequent cascading system failures, to exclude any social, economic, or political responses that exacerbate or reduce failure rates.

- By "Systems," we refer not only to a country's network systems (broadly defined to mean any network that moves something--e.g., bytes, people, electricity), but also its political, economic and social systems, with the key attributes of robustness being:

- Distributiveness

- Recovery capacity

- "Workarounds" capacity

- Trust "capital."

Having defined the extremes of our axes, we break down the four quadrants in the following manner:

- Best Case is when Y2K events are discrete and episodic and systems are robust

- Next Best Case is when the Y2K event is widespread and sustained, but systems are robust

- Next Worst Case is when Y2K events are discrete and episodic, but systems are vulnerable

- Worst Case is when the Y2K event is widespread and sustained and systems are vulnerable.

Slide 4: The X-Y Axis for Y2K Onset Models

Slide 4: The X-Y Axis for Y2K Onset Models

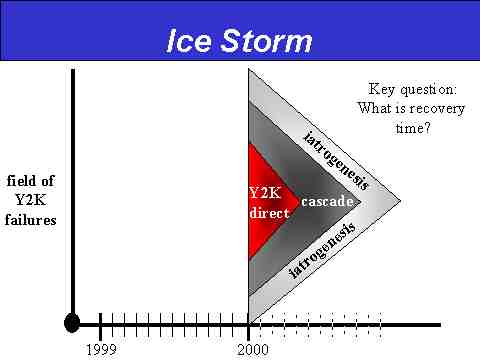

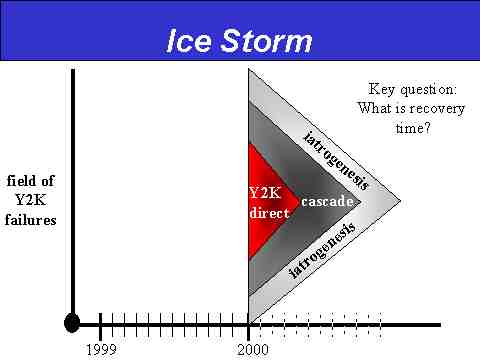

Y2K Onset Model #1: The Ice Storm

The Ice Storm onset model is depicted in Slide 5 below.

In the embedded chart, the vertical axis defines a "field of Y2K failures," meaning we're not going to offer any percentages or "hard numbers" here, just a rough notion of overall failure saturation. Along the vertical axis we display the years 1999 through 2001, with the months of 1999 noted in solid-line marks and the months of 2000 noted in dashed-line marks. The difference between the two markings is meant to suggest that while we may feel we have a firm grasp of appropriate time units for the timeline leading up to 010100, perceptions of time's passing once we pass through the 010100 threshold may vary greatly depending on locale. For example, the subjective time unit of note for Wall Street at the beginning of January may be the first day of trading--a mere several hours' time, whereas the subjective time unit of note for a sheep herder in a less developed country may be as long as until the first time he brings his sheep to market--possibly several weeks.

Slide 5: The Ice Storm Onset Model

Slide 5: The Ice Storm Onset Model

The Ice Storm onset model offers the classic, TEOTWAWKI view of Y2K: it hits en masse on or about 010100 and strikes virtually every aspect of society. To the extent that such a model may seem to hold true on a perceptual basis in any one locality or region (meaning, for all practical purposes, it seems as though all systems are impacted to some disabling degree), we posit that the Ice Storm's components are logically broken down into three categories:

- Direct Y2K failures

- Cascading system failures resulting from the direct failures

- Iatrogenic crisis management or social responses that exacerbate the cascading failures or trigger new threads.

While this model held implicit sway during much of the Y2K debate in 1998, it has receded in prominence over the course of 1999, as remediation efforts make clear that this is not a useful universal model. Having said that, however, we believe the model retains great validity for understanding pockets of significantly damaging Y2K impact that may occur around the world, meaning those areas where--for all practical purposes--the TEOTWAWKI notion may well emerge among significant portions of a population battered by widespread network failures.

Of course, even here we're still talking only about the perceived onset, and not some sustained environmental status that would realistically drag on for months. As such, the key question for the Ice Storm onset model is, "How fast can the society or economy in question recover by necking down the failure rate to some level commensurate with reasonably sub-optimal functioning (meaning, for many around the world, the return to "life as we know it")?"

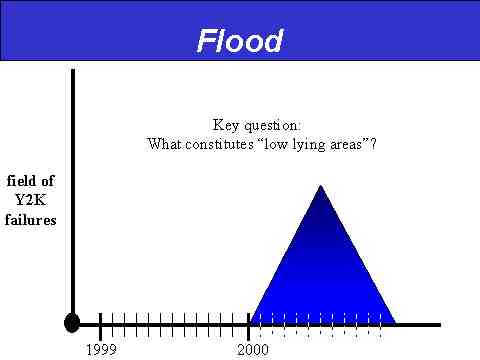

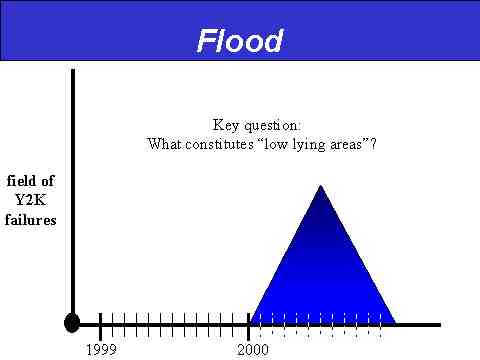

Y2K Onset Model #2: The Flood

The Flood onset model is depicted in Slide 6 below.

Slide 6: The Flood Onset Model

Slide 6: The Flood Onset Model

The Flood onset model depicts a slow but inexorable bulge of network failures that first rises above the usual "background noise" level on or about 010100 and then expands for something in the range of the first six months of 2000, peaking near the end of the 2nd Quarter or at some point in the 3rd Quarter. In some ways, we could suppose the same breakdown of elements (direct, cascading, iatrogenic) here as with the Ice Storm model, but because of the greatly extended timeline (thus allowing for more effective crisis management and network triage), we limit our description here to direct and cascading network failures, thus positing a peak failure rate somewhere in the range of 50 percent of all networks.

As such, the Flood model gets nowhere near the TEOTWAWKI pain range, but instead describes something more akin to a significant economic downturn, most likely corresponding to popular perceptions of a recession or financial market "correction." In that manner, the Flood model possibly describes a more profound economic impact than the Ice Storm, which, while it is a shock to the system, is probably of shorter duration. So, like the Ice Storm, the Flood model involves an interrelated sequence of network failures, albeit with a far smaller immediate impact on the overall functioning of society.

In keeping with the weather analogy, the key question for the Flood model is, "What constitutes a 'low-lying area?'" One example of a potential low-lying area would be manufacturing, whose network failures would not likely be centered on the 010100 threshold, but rather build up over time as production continued throughout 2000. Another could be medical supplies, especially the production and distribution of key pharmaceuticals. Still another might be the processing and distribution of clean drinking water.

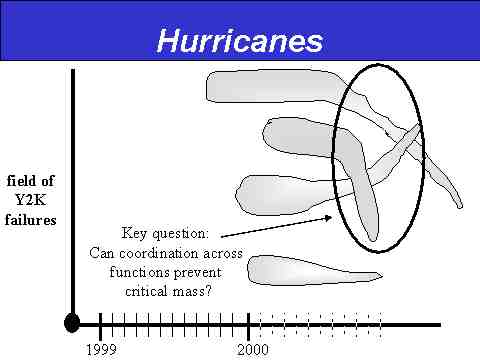

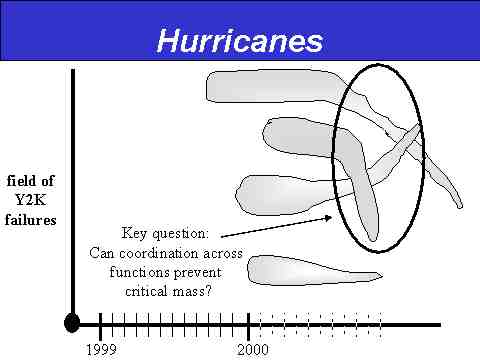

Y2K Onset Model #3: The Hurricanes

The Hurricanes onset model is depicted in Slide 7 below.

Slide 7: The Hurricanes Onset Model

Slide 7: The Hurricanes Onset Model

The Hurricanes onset model presents a series of sectorally-limited (meaning unconnected across sectors) but relatively lengthy (meaning some cascading effect) constellations of network failures. In effect, this model is a hybrid of the Ice Storm and Flood models. The Hurricanes model packs the same immediate punch as the Ice Storm model, albeit in isolated "low-lying areas" (echoing the Flood model), thus limiting the overall impact on the functioning of a society.

The Hurricanes model speaks more to the "winners and losers" approach to thinking about Y2K's ultimate impact: some sectors of society will seemingly get off scot-free, while others will seemingly suffer great damage. The key difference with the Flood model is the lack of interrelation and simultaneity, so rather than employing the economic language of "downturns," we're more likely to describe "shake-ups" in one or another industry.

The same approach to identifying vulnerable sectors that one uses with the Flood model would apply here, although in an overall sense, the Hurricanes model is probably best used to think about countries whose remediation efforts have been weak, for here we run into the notion of over-confidence possibly leading to poor crisis management preparation. If such "poor remediators" turn out to be far more vulnerable than they realize, then the key question becomes, "How can coordinated triage and crisis management avert the appearance of a critical mass of substantial--yet still relatively isolated--network failure clusters?"

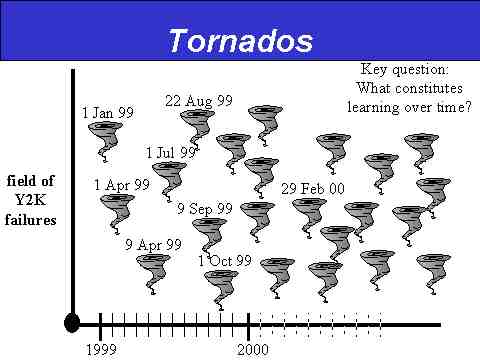

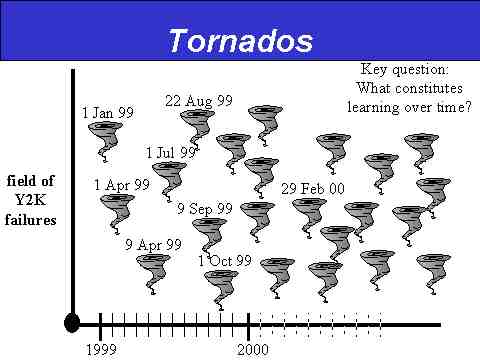

Y2K Onset Model #4: The Tornados

The Tornados onset model is depicted in Slide 8 below.

Slide 8: The Tornados Onset Model

Slide 8: The Tornados Onset Model

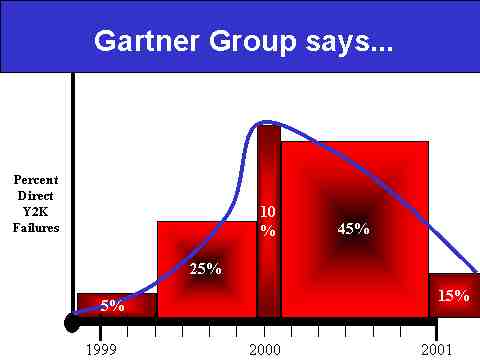

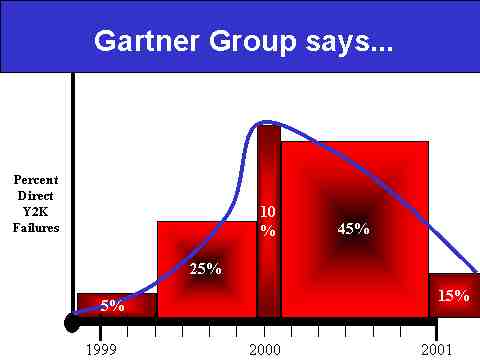

The Tornados onset model refers to a "season" of sectorally- and temporally-limited Y2K-induced network failures. This model is the closest to a null hypothesis of Y2K's overall impact, for, in many ways, it describes life as we know it, albeit with a higher-than-average failure rate. The Tornados model can likewise be thought of as the "key dates" model, for the two go naturally hand-in-hand when one seeks real-world evidence of significant network failures that either produce serious disruptions of service or require extraordinary efforts at repair. For if such key dates come and go without displaying any significant failures, meaning they're so big they can't be hidden by the service providers in question, then these Y2K milestones pass by without registering significant values on any sort of TEOTWAWKI scale, becoming the Y2K equivalent of a "tree crashing in the forest when no one's there to hear it."

The "key dates" approach does correspond nicely with the Gartner Group's predictions of Y2K failure rates rising and falling over the course of 1999 and through the year 2001, but the big deficiency of this model to date has been the lack of any stunning failures on key dates that have already passed. For example, no failures featuring major negative impact occurred on 1 or 3 January, the first day and business day, respectively, of 1999. The start of many fiscal year programs on 1 April also failed to reveal any serious disruptions for the governments involved. The so-called "nines" problem that was slated to appear on 9 April likewise produced no failures of great societal value in any country around the planet. Most recently, the 1 July threshold came and went with no apparent damage to the 46 U.S. states whose fiscal years began that day.

Meanwhile, Cap Gemini America, the computer consulting firm, declares on the basis of their recent survey of Fortune 500 companies and a smattering of U.S. government agencies that close to three-quarters of the respondents report experiencing a Y2K-related failure through the first quarter of 1999. But if these firms are having these failures and none are making any headlines, how is that much different from everyday life as we know it? Aren't private firms and government agencies experiencing network problems on a fairly regular basis, and just as regularly keeping such failures under wraps? The key missing data involve how much different 1999 is turning out to be compared to any previous year, meaning what is the "instability added" from Y2K? And that's the data we haven't found anywhere yet.

Having said that, the key question for the Tornados model remains, "What constitutes good learning over time?" For example, should our confidence grow due to the lack of Y2K headlines stemming from the key dates already passed? Or should we ignore most if not all of that success, especially for a pure fellow traveler such as the "nines" problem? After all, we can get fixated on Y2K key dates all through 1999, get through them all quite nicely, and still suffer significant tumult on 010100. Uneventful key dates make that seem less likely, but don't rule out it out by any means.

Onset Models Leading to Generic Y2K Outcome Scenarios

Of course, none of the four onset models are likely to hold sway for any one region's entire Y2K experience, and in that sense, we are likely to see versions of all four models occurring simultaneously around the planet at various points in the Y2K Event. As ideal types, the four models are designed to help the reader disaggregate the complexity presented by Y2K's myriad of possibilities, rather than provide a "pick one of four" analytical choice that would invariably prove false and pointless.

Slide 9: The Onset Model Arrayed on the X-Y Axis

Slide 9: The Onset Model Arrayed on the X-Y Axis

Slide 9 above arrays the four onset models on our X-Y axis, and the placement should seem fairly intuitive given our descriptions:

- Tornados represent the "Y2K events as discrete and episodic" and "systems are robust" quadrant, meaning a season of relatively isolated and concentrated damage that follows little rhyme nor reason to the extent that we can trace causality.

- Flood represents the "Y2K event as widespread and sustained" but "systems are robust" quadrant, meaning a rising tide or deluge of damage that follows the logic of systematic vulnerability, i.e., the low-lying areas analogy.

- Hurricanes represent the "Y2K events as discrete and episodic" but "systems are vulnerable" quadrant, meaning a season of somewhat isolated but wide-swath damage that follows the logic of either poor remediation or unforeseen vulnerabilities--basically one in the same.

- Ice Storm represents the "Y2K event as widespread and sustained" and "systems are vulnerable" quadrant, meaning a seemingly pervasive or all encompassing damage pattern that is inescapable, but one that at least reveals itself in its entirely with great speed, thus facilitating recovery.

Again, our rationale in presenting such onset models is not to encourage a "pick one" mentality, but rather to break down the abstract nature of the potentially universal problem set into a series of weather analogies that are far more easily understood by the average citizen--not to mention your average elite decision maker.

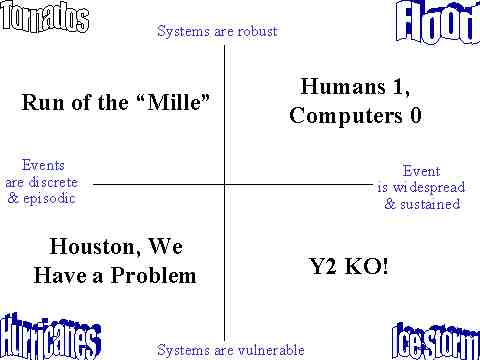

Slide 10 below presents a series of outcome-focused Y2K scenario titles arrayed along our X-Y axis. By pairing them up with our onset models, we--in effect--offer a "coming and going" view of the Y2K Event (leaving the "guts" of our Y2K analysis for the section on Scenario Dynamics).

Slide 10: Outcome Scenarios Arrayed by Y2K Onset Models

Slide 10: Outcome Scenarios Arrayed by Y2K Onset Models

- Run of the "Mille" refers to the Best Case Scenario, meaning Y2K comes in bits and pieces and we prove far more robust than we give ourselves credit for. So it's "run of the mill" in that we take Y2K in stride, but Run of the "Mille" in the sense that the Millennial Date Change Event still exists at the core of the Y2K null hypothesis. Thus, in this scenario, whatever social instability occurs around the 010100 threshold is more driven by millennial elements (e.g., apocalyptic-driven behavior, world's largest party, great religious feast) than by actual Y2K-driven network failures. Humanity emerges on the far side of this "crisis" wondering what all the hype was about.

- "Humans 1, Computers 0" refers to the Next Best Case Scenario, meaning Y2K is big and bad but we weather the deluge of failures and only the systematically weak are left with permanent damage. This is the Nietzschean social scenario that says, that which does not collectively kill us, makes us collectively stronger. Humanity emerges on the far side of this crisis with a renewed confidence vis-a-vis the invisible and pervasive information technology that "seems" to control so much of our lives.

- "Houston, We Have a Problem" refers to the Next Worse Case Scenario, meaning Y2K comes in bits and pieces but we are surprised to realize how fragile our systems are. Like the Apollo 13 mission from which this quote was drawn, it seems as though relatively minor weaknesses--the IT-equivalent of an Achilles' heel--sequentially disable many sectors of society with ferocity, leading to cascading failures that can threaten the sum of the whole. Humanity emerges on the far side of this crisis split into winners and losers, meaning--respectively--those who proved resilient and those whose weaknesses were exposed. In some ways, Y2K will unfold something like a computer virus: those with sufficient immunity will survive just fine, while those with weakened immune systems will suffer catastrophically.

- "Y2 KO!" refers to the Worst Case Scenario, meaning Y2K is big and bad and we're far more vulnerable than we realized. We are collectively "knocked to the mat," with the real uncertainty being, do we get back up before the "referee" finishes his "count?" Or do we lie there prostrate, dazed and confused? Of course, at some point we do get up, and how humanity emerges on the far side of this crisis is largely determined by the nature of the "knockout." Is Y2K merely a "TKO," meaning a "knockout" attributed solely to "technical" failures? Or is Y2K a genuine "whupping" where all our systems (political, economic, social, and network) fail us miserably? In other words, are we merely embarrassed and so continue on as before? Or are we truly humbled and thus serious changes result?

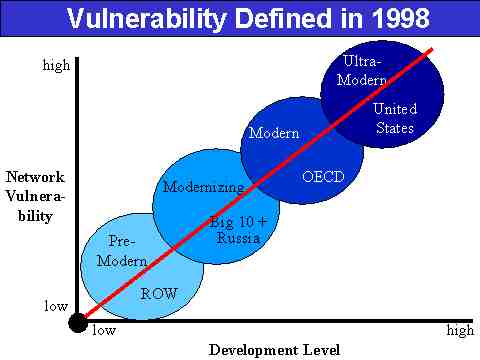

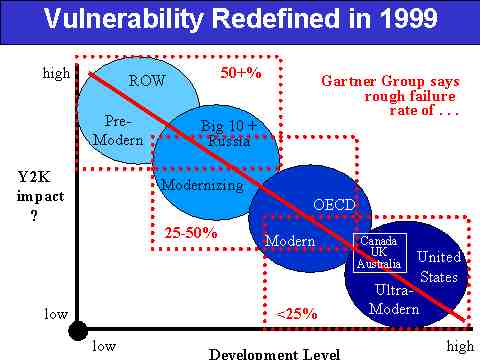

Potential Y2K Impact by Country Groups: Conventional Wisdom Has Changed Over Time

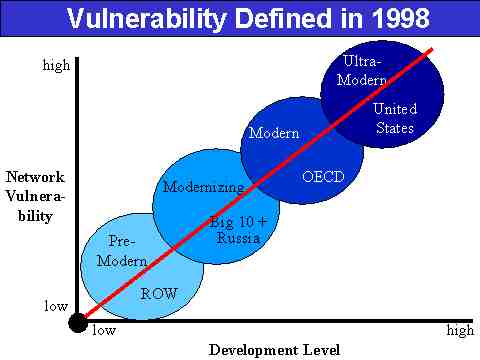

The conventional wisdom on which countries around the world are more vulnerable to Y2K has changed dramatically over the past year. We display our interpretation of this changing debate in the following two slides.

First, a word on how we break down the world into four IT categories:

- We define an "Ultra-Modern" IT category as including only the United States, which, by all measures, stands head and shoulders above the rest of the planet in terms of IT adoption rates. To put it bluntly, there's no way Y2K will be bad enough to derail the US's progressive adoption of IT. There's simply no going back.

- A "Modern" IT category basically captures the rest of the OECD-type states (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development) such as Japan, Germany, France, etc. These economies tend to be relatively distributed in terms of networks, but not nearly as "New Economy" in outlook or practice as the U.S. Like the U.S., these countries are unlikely to see the further adoption of IT derailed by Y2K, although it could greatly influence some of the choices they make in coming years.

- The "Modernizing" IT category corresponds to Jeffrey Garten's list of the "Big Ten" emerging economies, with the addition of Russia. Garten's "big ten" are:

- China

- India

- Indonesia

- South Korea

- Turkey

- South Africa

- Poland

- Mexico

- Argentina

- Brazil.

What's most immediately noticeable about this group is that you're talking about the bulk of the world's population, not to mention several that recently experienced serious economic tumult (or at least serious buffeting) in the Global Financial Crisis of 1997-98. With this group, you're also talking about countries that have adopted IT in a huge way only in the past decade or so, so Y2K has some potential here to trigger a bit of a technology backlash if its overall impact is bad enough.

- The "Pre-Modern" IT category bundles up the Rest of the World (ROW). Here we're talking about countries with low IT penetration rates.

Slide 11: Conventional Wisdom on Potential Y2K Impact (1998)

Slide 11: Conventional Wisdom on Potential Y2K Impact (1998)

Slide 11 above displays the conventional wisdom that we consistently bumped into when we began our research back in the summer of 1998. In short, the broad assumption implicit in most writings about Y2K's potential impact was that there was a direct relationship between a country's development level and its potential vulnerability on Y2K-induced network instability. Following this rule, an ultra-modern IT country like the U.S. was the most vulnerable, while Pre-Moderns like a Haiti or Somalia were least vulnerable. On the face of it, this made perfect sense, because you can't be harmed by breakdowns in what you don't have--or so it seemed. This thinking likewise tracked with much military strategizing regarding Information Warfare, which also posited that the more IT-intensive your society was, the more vulnerable it was to Information Warfare.

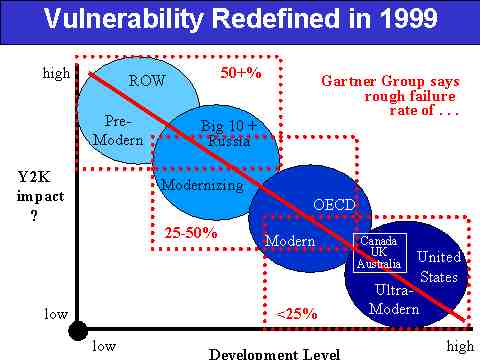

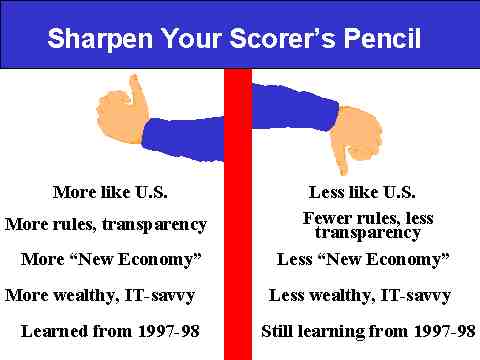

Slide 12: Conventional Wisdom on Potential Y2K Impact (1999)

Slide 12: Conventional Wisdom on Potential Y2K Impact (1999)

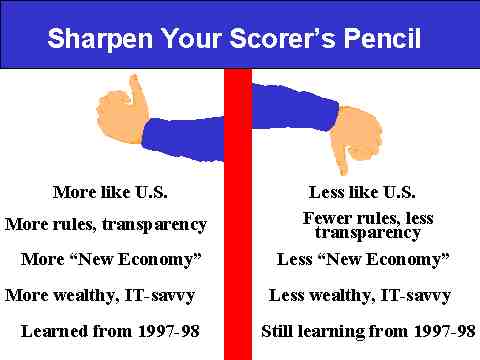

What a difference a year makes! Or so it seems if you buy into the Gartner Group's estimates of likely Y2K network failure rates by country (see Slide 12 above). Now everyone knows that the Gartner Group's data is heavily based on the self reporting of the countries in question (or the private firms within those countries), so taking this very rough estimate with a grain of salt, you're nonetheless faced with a stunning reversal of fortune that's apparently occurred solely on the basis of the remediation efforts each country has or has not pursued over the last year. In short, from the perspective of failure rates, the U.S. goes from most vulnerable to least vulnerable, along with a host of like-minded states (e.g., Canada, United Kingdom, Australia). On the other end of the spectrum, the countries looking at the highest failure rates are the modernizing countries, such as China and Russia, and the IT Pre-Moderns, such as a Vietnam and Zimbabwe.

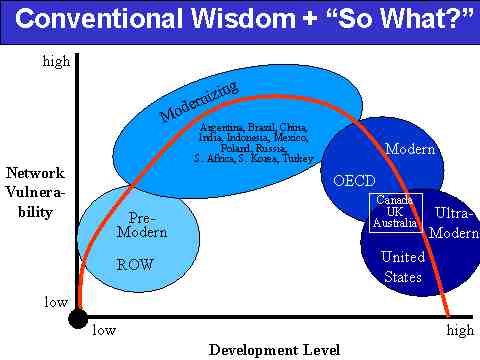

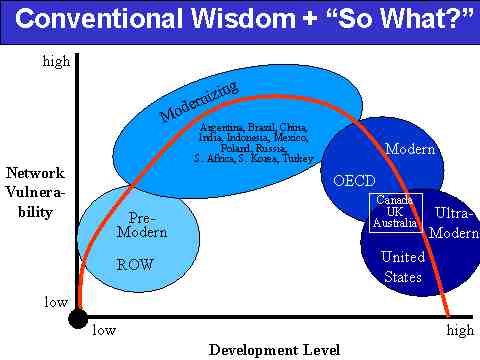

Slide 13: The So-What Filter Applied to Today's Conventional Wisdom on Country Vulnerability

Slide 13: The So-What Filter Applied to Today's Conventional Wisdom on Country Vulnerability

While failure rates (the percentage of system failures) are expected to be much higher in the pre-modern and modernizing countries than they are in the U.S. or OEDC nations, failure rates do not, by themselves, describe the whole picture. As noted earlier, IT is far more integrated into the economies and infrastructure of modern countries than those of emerging and modernizing nations. Consequentially, 25 percent system failure in the U.S. is likely to be much more significant than a 90 percent failure in a small pre-modern nation. In the most primitive of these, even 100 percent system failure is likely to be below the event horizon; while even 10 percent system failure in a modern IT-intensive economy could result in significant economic upheaval. As suggested in Slide 13, when all the factors—remediation effort, dependency on IT, network maturity, distribution and redundancy of the architecture—are integrated, the nations that seem to have the most to fear from Y2K would seem to be those in the process of modernizing. In general these tend to be increasingly dependent on IT, but have not been able to spend much money on remediation and have not developed the highly distributed and redundant networks of the U.S. and other modern nations.

So really, in the short span of about 12 months, the conventional wisdom on which countries are most vulnerable to Y2K has been dramatically reversed. Like the original conventional wisdom before 1999, this one also makes eminent sense when you think about it: rich countries with a lot more to lose and a lot more disposable income to throw at the problem have succeeded most in remediating the Y2K threat into something more manageable. Meanwhile, countries new to the IT scene, whose awareness of Y2K lagged significantly behind that of more advanced IT countries, tend to possess less resources to throw at the problem. Moreover, they tend to pirate software more and, as such, pay less attention to system administration concerns such as Y2K or viruses such as CIH. In that sense, the destructive path of CIH, the so-called Chernobyl virus, may well prove to be reasonably predictive of Y2K's ultimate impact--namely, more serious in Asia, Latin America, and the Middle East than in Europe or North America.

Matching Country Groups With Y2K Onset Models

So, to the extent that we're willing to go out on a limb regarding which country groups are likely to experience which Y2K onset model, our best guess would be as portrayed in Slide 14 below.

Slide 14: How Y2K May Go Down By Country Groupings

Slide 14: How Y2K May Go Down By Country Groupings

By arraying the countries across our X-Y axis, we're not so much predicting how we think Y2K will unfold for each and every country belonging to each grouping as suggesting that if any one of the onset models is going to be strongly associated with a particular development or IT-intensiveness level, they are likely to correspond as follows:

- We see the U.S., along with very similarly structured near Ultra-Modern states such as Canada, Australia, and UK, probably experiencing the Tornados onset model, meaning that Y2K comes in bits and pieces and the countries are essentially robust. Gartner predicts several other advanced European states, along with Israel, will fall into this category. Correspondingly, this country group would likely experience the outcome scenario described as Run of the "Mille."

- To the extent that many important Modern states, such as France, Germany, Italy and Japan, have not progressed nearly as much as they might have in the time allotted, we expect that this country grouping may experience something closer to the Hurricanes onset model. In short, we see the damage stemming from Y2K failures to be more significant than it might have needed to be because those countries enter into the situation more vulnerable than they realize. Correspondingly, this country group would likely experience the outcome scenario described as Houston, We Have a Problem.

- If the Ice Storm model actually occurs, we believe it's most likely to happen to a Modernizing country, such as a Russia, China, India, Poland, or Turkey. Here, Y2K may hit with far more force both because remediation has been weak and because these countries' systems are--in general--more vulnerable to disruptions. Correspondingly, this country group would therefore be more likely to experience the outcome scenario described as Y2 KO!.

- It is in the IT Pre-Modern category that we expect to witness the Flood onset model, or the slow build-up of progressive failures. While these countries' systems in general tend to be more robust in the sense that they are more used to "doing without" or "working around problems," it may well be the slow but steady deluge of many small failures that causes Y2K to seem like a widespread and sustained event that drags out over several months. Good candidates for Flood status would therefore be less developed states in Latin America, Africa, the Middle East, and South and Southeast Asia. Correspondingly, this country group would likely experience the outcome scenario described as Humans 1, Computers 0.

IV. The M Curve of Influence

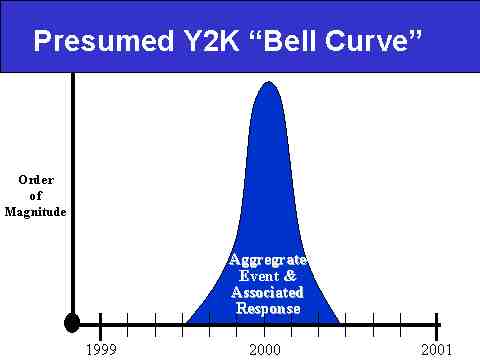

Understanding Where Opinion Leaders Can Influence Social Response

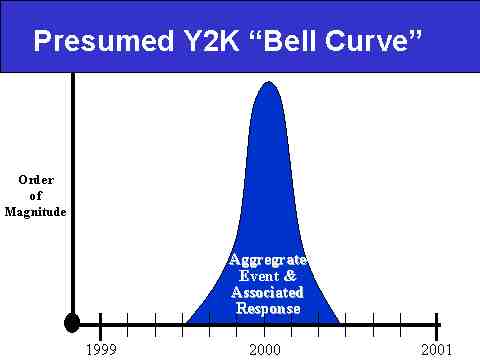

The strategic vision of Y2K we have encountered again and again, both in our Internet-based research and in our many discussions with experts and ordinary citizens from around the world, is that the event will unfold, peak, and then disappear--all with great speed--in a tight timeline surrounding the Millennial Date Change Event. In effect, what the majority expects is a very tall Bell Curve surrounding 010100, which we depict below in Slide 15.

Slide 15: The Y2K Bell Curve Too Many People Expect

Slide 15: The Y2K Bell Curve Too Many People Expect

In other words, the conventional expectation is that Y2K failures will:

- Ramp up dramatically along an asymptotic curve in the last couple of months in 1999

- Experience a rapid topping off in the first few days of 2000

- Decrease in a similarly steeped downward curve until basically disappearing as a phenomenon of note somewhere in the middle of the First Quarter of 2000.

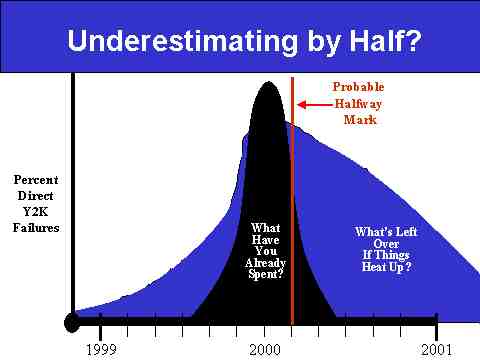

The problem with this view is three-fold:

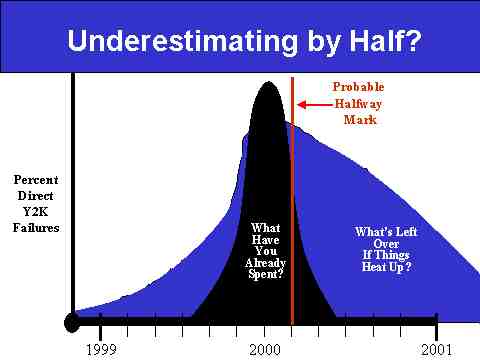

- It tends to draw off strategic resources from both mid-1999 and the rest of year 2000 (and beyond) and concentrates crisis management approaches on the 010100 threshold.

- It inaccurately reflects the likely spread of Y2K-related network failures, as predicted by the Gartner Group.

- It fools decision makers into thinking that not only will their influence be best used in a concentrated fashion around the 010100 threshold, but that it will likewise be effective during that specific period.

We believe one or more of these three mistaken assumptions are incorporated--to some degree--in much if not all of the strategic planning for crisis management of the Y2K Event around the world.

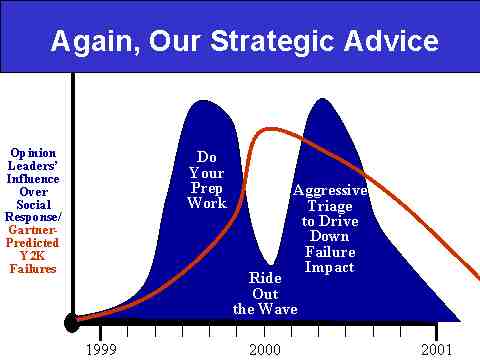

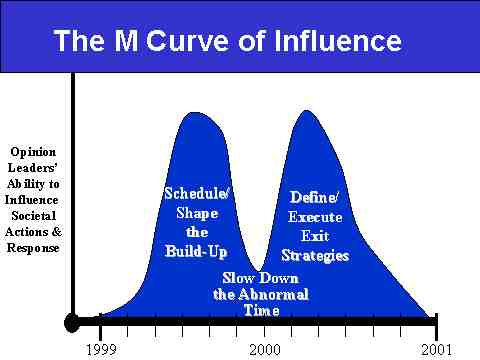

Instead of focusing on a Bell Curve perspective regarding Y2K's onset and unfolding, we argue that Opinion Leaders, whom we'll define as anyone with the power to influence the actions of others, should instead approach the Y2K timeline with the following three assumptions in tow:

- Your best time to influence social response is during the months leading up to Y2K's onset, with an emphasis on reasonable mass preparations, the establishment of crisis management arrangements, and the shaping of popular perceptions as to what will likely lie ahead.

- Your influence will disappear in the last few weeks and days leading up to the 010100 threshold, as the public will have largely made up its mind regarding individual preparations and strategies for experiencing--not to mention celebrating--the Millennial Date Change Event and the associated onset of Y2K; moreover, your influence will never be lower than on 010100, when your ability to control mass events will essentially approach zero.

- Your influence will reemerge once the Millennial Date Change Event expires and the true nature of Y2K's unfolding--however bad or minor that may be--makes itself apparent to you and society, for at that point you will have problems to solve, targets for resource allocation, etc.--in short, the battle will be joined.

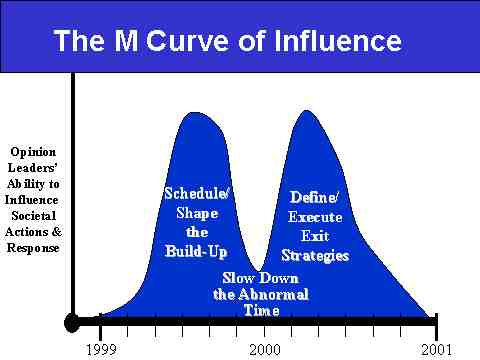

Slide 16: The M Curve of Influence Explained

Slide 16: The M Curve of Influence Explained

Thus our "M Curve of Influence" (Slide 16 above) describes both the utility of Opinion Leaders' efforts before (Schedule/Shape the Build-Up) and after (Define/Execute Exit Strategies) Y2K's onset, while emphasizing the loss of influence over societal actions and response during the actual onset (Slow Down the Abnormal Time). In short, our strategic advice mantra would be:

Organize . . . Relax . . . Attack

Explaining the First, or Pre-010100 "Hump" of the M Curve

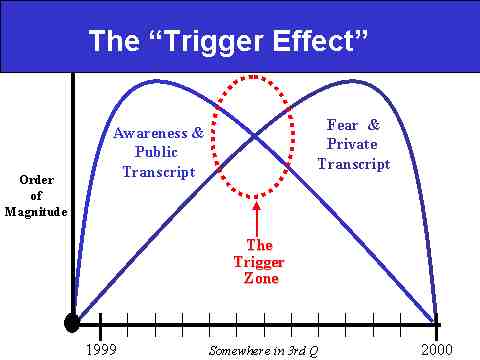

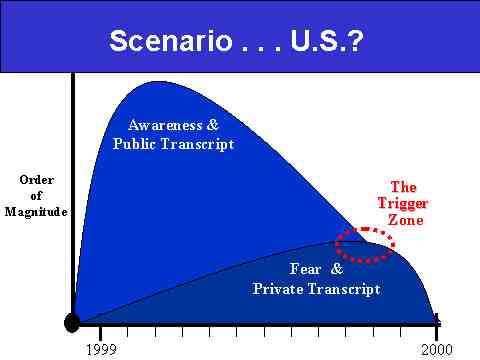

We ascribe the first hump of the M Curve, or the bulge of influence we think Opinion Leaders enjoy over the summer and fall of 1999, to what we describe as the popular competition between awareness and fear regarding Y2K and the associated Millennial Date Change Event. Slide 17 below explains this competition.

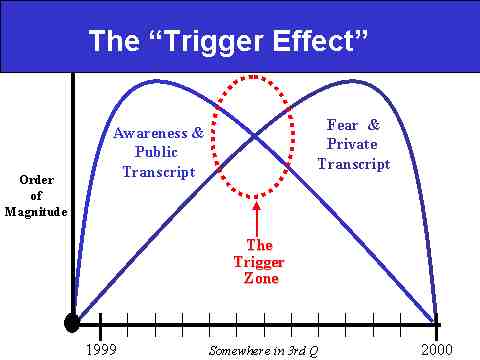

Slide 17: The "Trigger Effect" Explained

Slide 17: The "Trigger Effect" Explained

The first thing to note on the slide is our humility. The vertical axis is labeled "Order of Magnitude," which is just a fancy way of saying we're theorizing about a very complex phenomenon and thus can only describe it in rather vague terms. The timeline, on the other hand, is fairly straightforward--namely, we're talking about 1999.

It's our general hypothesis that no matter what country you're talking about, awareness of Y2K will precede--and in some ways, trigger--fear about Y2K. In a generic situation, then, we're describing the rise of "Awareness and the Public Transcript" as occurring more in the first half of 1999 than in the second half, meaning most people heard and came to understand Y2K in the initial sense in early 1999. This happened primarily as a result of their being flooded with all sorts of Public Transcripts about the state of remediation efforts and the (typically) non-likelihood of Y2K-related failures come 010100. Public Transcripts can be described as authoritative statements by authoritative people. They typically highlight a rosier-than-average perspective on Y2K, quite often out of official fear of "alarming the public unnecessarily." Of course, much of the awareness-raising effort encapsulated in such Public Transcripts requires "scaring" the public enough to take action, and therein lies the rub.

As we enter into the summer and fall of 1999, the Awareness and Public Transcript wave begins to give way (i.e., awareness has peaked) to the Fear and Private Transcript wave, which is likely to peak in the last few weeks and days of the year. The fear part of the equation is nothing more than anxiety over the uncertainty caused by the looming event, whereas the Private Transcript describes the "off-line," unofficial, or individual preparations and/or decision making regarding how a person, economic firm, national government, etc., plans on either enacting or following a particular rule set for what it perceives will be the crisis period surrounding Y2K. So, for example, the differences between a Public and Private Transcript could be as follows:

- An individual's Public Transcript could be that he or she is administrator of a small town and thus plays a prominent role in community preparations and perception management while simultaneously engaging in the Private Transcript of stockpiling food, water, and weapons at home.

- A firm's Public Transcript could be publicizing the success of its remediation effort while its Private Transcript could be its quiet stockpiling of key industrial material inputs, the cutting of ties with suppliers and vendors it does not deem sufficiently compliant, or the preparation and public announcement of new rule sets.

- A government's Public Transcript could be publicizing how all essential services will survive the Y2K Event intact and without any disruptions while quietly establishing all sorts of emergency procedures to deal with just such failures.

We describe the point in the year when the Awareness and Public Transcript wave is surpassed by the Fear and Private Transcript wave as constituting a Trigger Zone of sorts. This is where we believe the manic, or Mania Phase of Y2K begins. In short, this is when you will see individuals, firms, and perhaps even governments start to exhibit extraordinary behavior in response to whatever they believe "others" in society may do--i.e., the fear of fear itself.

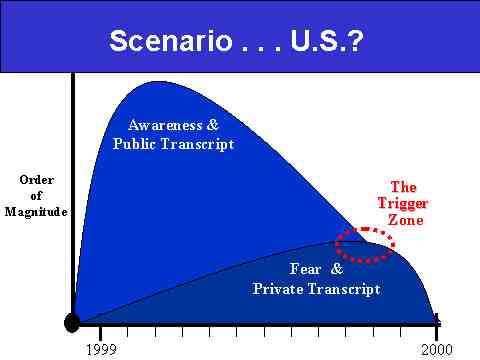

Slide 18: What the Trigger Zone Might Look Like in US

Slide 18: What the Trigger Zone Might Look Like in US

Having said all that, we want to be careful not to leave readers with the impression that we're predicting a serious "freak out" factor for the United States come Labor Day, for it is by no means a given that the Fear and Private Transcript must overwhelm the Awareness and Public Transcript wave. In effect, if Opinion Leaders do their job correctly in terms of the Awareness and Public Transcript effort, the Fear and Private Transcript wave can be greatly reduced (see Slide 18 above). By way of analogy, think of how Wall Street spent much of the 1990s educating Baby Boomers about the dangers of yanking their money out of mutual funds at the first sign of trouble. Then think about how well that effort paid off during the Global Financial Crisis of 1997-98. In short, the better Opinion Leaders shape popular expectations, the less likely it is that Fear and the Private Transcript will balloon to dangerous proportions--not every knee has to jerk.

And indeed, it is our impression that as far as the United States is concerned, it is quite possible that the Fear and Private Transcript wave will remain marginal, meaning perhaps 15 to 20 percent of the population will engage in fear-based behavior that could be described as "excessive," understanding what a loaded term that is for many in the Y2K debate.

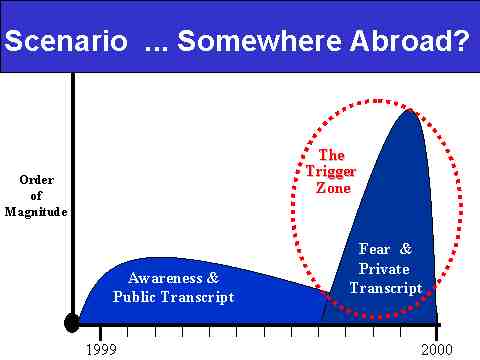

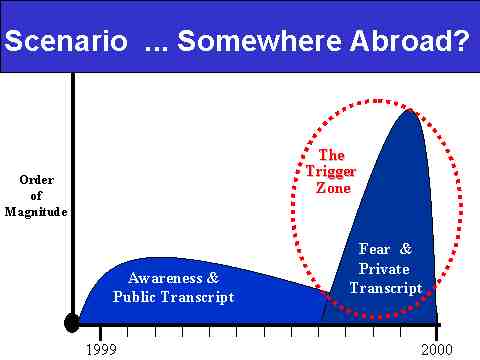

Slide 19: What the Trigger Zone Might Look Like Overseas

Slide 19: What the Trigger Zone Might Look Like Overseas