FT "analysis" full-pager on US-China trade by Alan Beattie. Starts by noting China's slight loosening of the yuan's peg and says this won't change the relationship all that much.

Then the key point:

With discontent rising across American business, fuelled by incidents such as the Google China censorship spat, Washington is recognising to its intense frustration that it lacks the instruments to conduct international trade policy in a modern economy.

“China is distorting global trade and investment patterns with a web of state-sponsored industrial policies,” says Jeremie Waterman of the US Chamber of Commerce. “The tools the US government has are inadequate to cope with this interlocking web.”

The old-fashioned architecture of US trade policy largely reflects the metal-bashing economy of the past. It is predicated – as is the focus on the exchange rate – on its manufacturers competing head-on with Chinese companies, particularly in the American market.

The US has a panoply of “trade defence” instruments – antidumping, countervailing duty and safeguard measures – that allow it to block imports it deems unfairly priced, state-subsidised or flooding in too rapidly. One such tool was used in September last year to restrict Chinese tyre imports, provoking a storm of protest from free-traders.

But the goods to which the US applies such measures are mainly basic, low-margin industrial components in which American competitiveness is being eroded against many countries. The list hit with trade defence protection in recent months does not read like a tour of America’s economic future: drill pipe, phosphate salts, coated paper.

Francisco Sánchez, undersecretary for international trade at the Commerce department, notes such products cover less than 3 per cent of US trade with China. Yet because the industries are long established and often have powerful labour unions, they exert disproportionate control over trade policy. When China joined the World Trade Organisation in 2001, the negotiators’ focus was on goods such as these, and particularly the eternally controversial area of garments and textiles.

The problems started after China joined the WTO and the the government protectionists were given more free reign under Hu and Wen, who, when they came to power, saw that few Chinese companies were predominant in the high-tech local markets and wanted to change that.

The problems started after China joined the WTO and the the government protectionists were given more free reign under Hu and Wen, who, when they came to power, saw that few Chinese companies were predominant in the high-tech local markets and wanted to change that.

From the piece:

Beijing says it is merely trying to do what other countries have done – modernise its economy, ascend the value chain and ease away from dependence on foreign companies for investment and technology.

But US companies say “indigenous innovation” goes way beyond familiar problems with software and movie piracy, and amounts to a full-blown system of government manipulation of large swaths of the economy.

Procurement is used to favour Chinese companies. Idiosyncratic technical standards such as a home grown wireless technology – “Wapi” – are given a clear run by denying licensing to more familiar international standards. Information, communication and technology companies complain about restrictions, such as requirements for products to be certified and tested in government laboratories, and for businesses to disclose source code.

Alarm about this is rising to the point where business representatives are increasingly prepared to criticise policy publicly. “We are feeling less and less welcome in China, which is why you are seeing more people speaking out and reconsidering their futures in China,” says John Neuffer of the Information Technology Industry Council.

Last week Jeffrey Immelt, chief executive of GE, expressed his growing concern about Beijing, telling an audience of Italian executives that “I am not sure that in the end they want any of us to win, or any of us to be successful”.

So the question for the US is, How to keep China's markets reasonably open for US company penetration while China seeks to fence those areas off for its own national flagships?--not exactly a new trick, I would add. Our trade instruments don't cover that scenario, the article argues.

How about suing China in the WTO?

But this strategy costs time and effort, and is not a cure-all. After the two or three years it can take to bring and win a case and an appeal, the remedy often comes too late. In the car-parts case, US business experts say, the delay gave Chinese industry more time to develop and American industry to weaken, foiling the goal of allowing US car-parts companies export significant quantities to China. Mr Neuffer notes that dispute settlement is even slower for high-tech industries, where product lifecycles can be less than a year.

In the end, no easy answer avails:

There are no strong rules about promoting competition in markets in WTO agreements. There is an agreement whereby governments commit to put public purchases of goods and services out to international tender but China has never signed.

“Government procurement in China is actually much more important to the American and European economies and companies [than issues such as textiles], but much less effort was put into getting China to join,” Mr Horlick says. China says it will make an offer to sign up this month but appears to have ruled out including regional and local government and state-owned enterprises, thus punching huge holes in any new commitment.

Debbie Stabenow, Democratic senator from Michigan, has proposed a bill that would cut China off from US government procurement if it does not open its own market. But few investors seem to think that would make a tremendous difference. Rules such as the “Buy American” provision already restrict China from bidding for some government contracts, against which Beijing has in turn complained.

So expect this relationship to remain tense as we seek to increase our exports in the face of Chinese efforts to dominate their own domestic market. It would seem that the only way we're going to correct a trade imbalance with China is to restrict their exports--a tricky path with someone who owns so much of your debt.

Monday, August 2, 2010 at 12:08AM

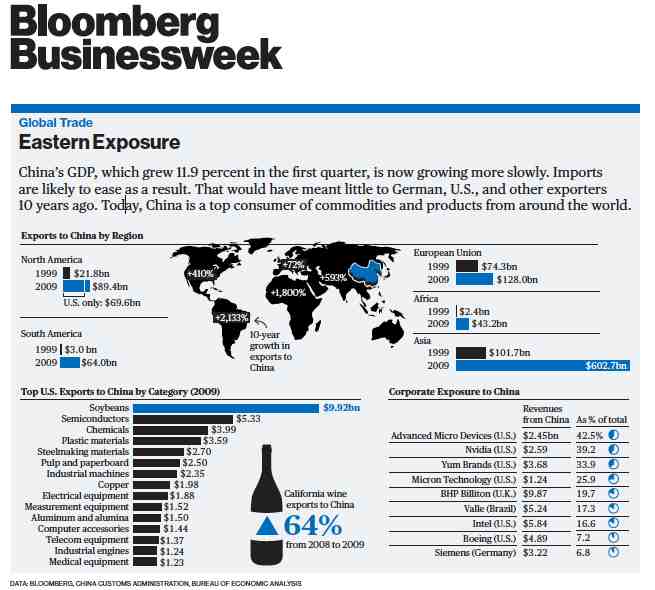

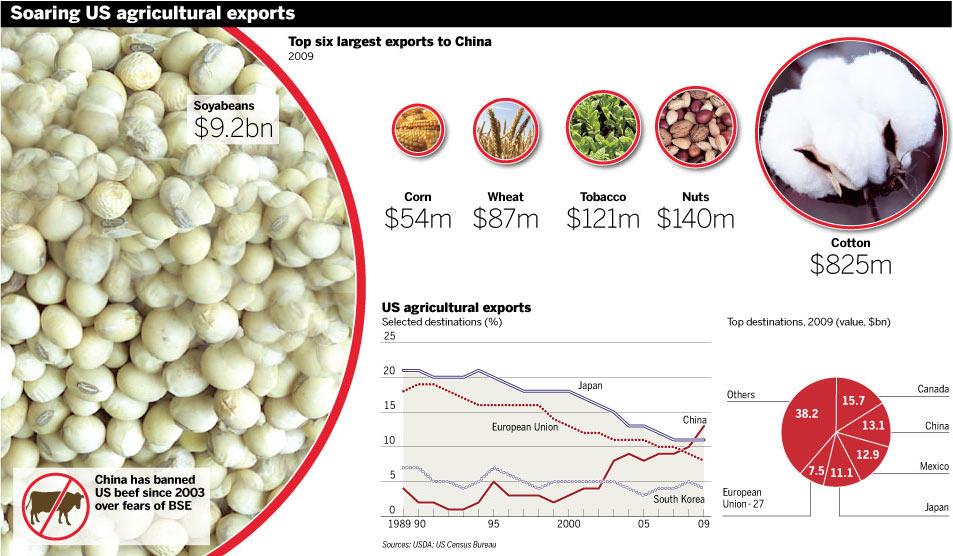

Monday, August 2, 2010 at 12:08AM  Nice FT story with charts on how “US farmers cash in on China demand.”

Nice FT story with charts on how “US farmers cash in on China demand.” China,

China,  agriculture,

agriculture,  global economy | in

global economy | in  Citation Post |

Citation Post |  Email Article |

Email Article |  Permalink |

Permalink |  Print Article

Print Article