Nice piece by David Ignatius at WAPO about the "power gap" in the US foreign policy establishment. He describes it as basically the missing link for all the complex security situations out there where the traditional "big war" US force isn't appropriate:

Here lies one of the biggest unresolved problem for U.S. national-security planners today: How can America shape events in an unstable world without putting “boots on the ground” or drones in the air? Does this stabilizing mission belong to the experts at the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID)? Or to the State Department’s Bureau of Conflict and Stabilization Operations, which was created in 2011 to deal with such problems? Or to the facilitators and analysts at the U.S. Institute of Peace, which was created in 1984 to help resolve conflicts peacefully? Or maybe to the covert-action planners at the CIA, who work secretly to advance U.S. interests in key countries?

The answer is that all of the above would have some role in shaping the U.S. response to a potential crisis. But in practice, the overlapping roles mean that none of them would have ultimate responsibility. Thus, in our imaginary NSC meeting, no one takes charge.

Actually, I called it the System Administrator force at first, and I said it would ultimately be more civilian than uniform, more USG than DoD, and more private-sector funded than fueled by foreign aid.

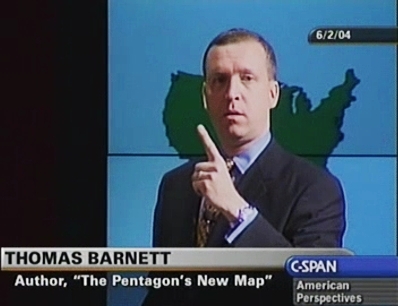

That was in The Pentagon's New Map, which Ignatius praised so much in a December 2004 WAPO column that he got me fired from the Naval War College a few days later (so yes, I have known what it was like to have your government career axed by a flattering MSM piece).

I haven't had a full-time job since - and never will again (by choice). As the old Roman proverb goes, A slave with many masters is a free man.

Then, in Blueprint for Action, I argued that my Sys Admin force needed a bureaucratic center of gravity in the USG for all the reasons Ignatius cites in this recent column, and I called the Department of Everything Else. And yeah, it was all about the "power gap" he describes there:

I’ve talked recently with officials from all these agencies, and what I hear is discouraging. They’re each heading in their own direction, working on their own particular piece of the puzzle. The pieces get assembled in well-managed U.S. embassies overseas, where the ambassador makes the country team work together. But similar coordination happens too rarely in Washington.

The U.S. Institute of Peace, headed by Jim Marshall, prides itself on being a small, nimble organization with a cadre of specialists who can travel to crisis zones and meet with different sects, tribes and parties. But the organization likes its independence and doesn’t want to be an arm of the State Department or any other bureaucracy. It’s a boutique, but that means its efforts are hard to multiply. And its presence can create confusion about who’s doing what.

State’s new Bureau of Conflict and Stabilization Operations has the right mission statement. But it’s only 165 people and shrinking, and it doesn’t even have the heft to lead the State Department’s activities, let alone the full government’s. The bureau’s chief, Rick Barton, wants State to designate a “center of gravity” for each budding crisis, so that there’s at least an address for mobilizing resources. It’s a good idea but just a start.

USAID has been America’s lead development agency for decades. But it’s also a perennial area of bureaucratic dispute, and many analysts argue that the nation gets less bang for its development buck than it should. It’s hard to imagine USAID being the strategic answer. The same goes for the CIA, which under John Brennan wants to refocus on its core intelligence-collection mission, rather than covert action.

It’s a cliche these days to talk about how America needs more emphasis on “soft power” and its better-educated cousin, “smart power.” Meanwhile, for all the talk, the problems fester and the power gap grows.

What I was told by many government types back then was that I was right, but that it could not happen until an entirely new way of thinking emerged on the subject - USG-wide.

Well, I spent the next decade trying to spread that thought both here in the US and in about four dozen other countries. I gave that talk about a thousand times (literally) to about half a million people - live and in person.

And I still try to spread that vision.

What I've said to people all along is that we simply need to suffer enough failure to finally realize that the old packages don't work. We can go in and blow everything up (Powell Doctrine, Bush in practice), or we can pretend a mafia-style decapitation/assassination campaign will work (Israel for decades, US under Obama).

But the real solution still hangs out there, waiting for us to get serious about finally addressing it - instead of chasing this "pivot" fantasy against the Chinese.

So no, the problem isn't going anywhere, and neither is the solution - sad to say.

But eventually it happens, because eventually we'll fear the change less than the repeated failures.

Hat tip to Jeffrey Itell for alerting me on the Ignatius column.

Tuesday, March 5, 2013 at 8:17AM

Tuesday, March 5, 2013 at 8:17AM