Top Ten Post-Cold War Myths

by

Thomas P.M. Barnett and Henry H. Gaffney Jr.

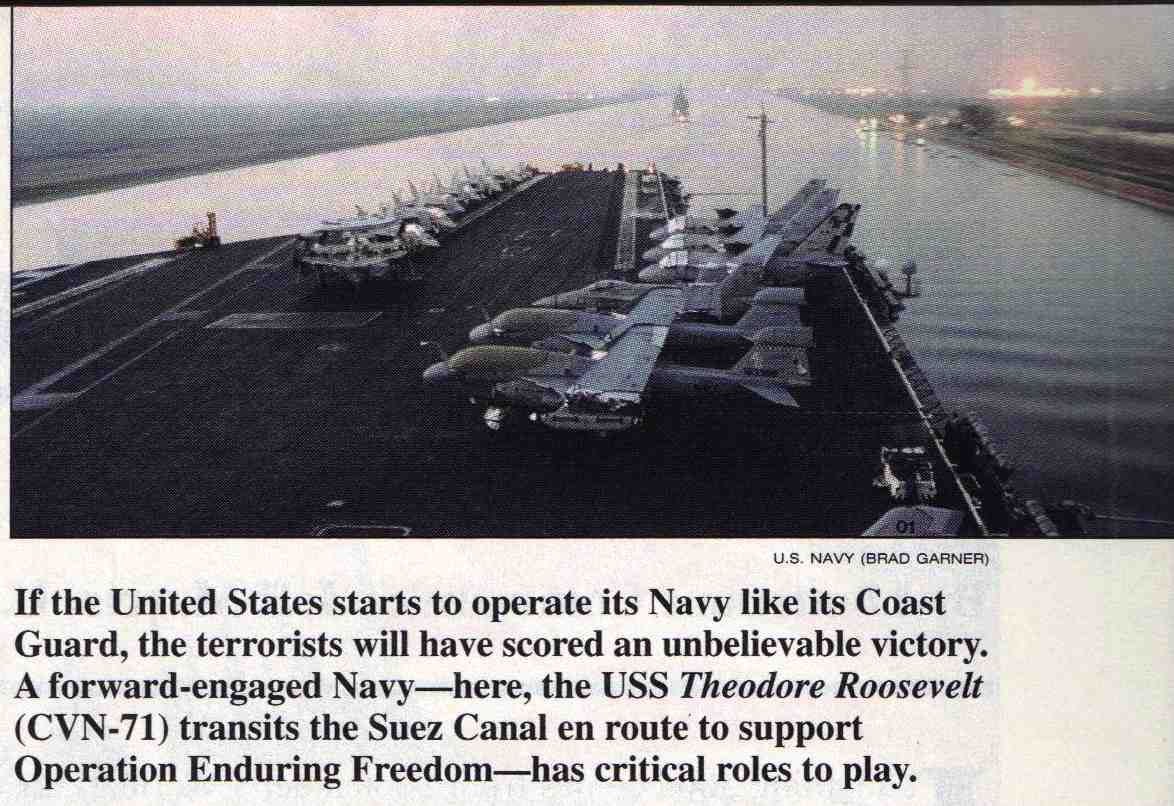

As a mobile, sea-based containment force,

the U.S. Navy will continue to play an

important role in the nation's foreign policy,

but its missions will mirror the clustered responses

in Iraq and Yugoslavia, not the

obsolete two-major-theater-war standard.

COPYRIGHT: The U.S. Naval Institute, 2001 (February issue, pp. 32-38); reprinted with permission

As we begin . . .

a new presidential administration, it is time to look over the recent past to see what we have learned about this new era of globalization. Americans entered the Clinton administration with a lot of hope about an outside world where so many positives had emerged with the end of the Cold War. The United States was the sole military superpower; what could go wrong?

Depending on whom you listen to, either a lot or not too much. Those experts who focus on the global economy see plenty to celebrate, but most who track international security see lots of threatening chaos in the world. How can these views be so different? Are there no connections between global economics and security? How can the former flourish if the latter is deteriorating?

We’ll say it up front: we don’t think international security has worsened over the past eight years. Instead, we think too many political-military analysts—in an attempt to justify the retention of Cold War forces—have let their vision be clouded by a plethora of post-Cold War myths, the biggest of which is the two-major-theater-war (2-MTW) standard. It was the best strategy placeholder then-Secretary of Defense Les Aspin could come up with to put a floor on force structure, but 2-MTW doesn’t capture the reality of the globalization era, the migration of conflict to the failing states outside that globalization, and the continued technological advances U.S. forces are introducing, which no other country pursues. In short, it is not connected to the world at all.

In our decades-long hair-trigger standoff with the Soviets, U.S. strategists became addicted to “vertical” scenarios, meaning surprise situations that unfold with lightning speed in a specific strategic environment that is, by and large, static. By static, we mean all potential participants are expected to come as they are. No one is really changed by the scenario, and no evolution is possible in their response. In this poker game, we expected everyone to play the single hand in question straight up: no bluffing, no hedging, and no changes of heart. In essence, we had to assume the two main players were rational actors. The only thing that seemed to change in this static picture was the race to add better technology. We always feared the Soviets had gotten there first, or were about to—a fear we subsequently transferred to the rogues.

This approach made sense in the Cold War, when we had to make certain gross assumptions about how both Soviet Bloc forces and our NATO allies would behave at the outbreak of World War III, but it just does not apply in the globalization era. If the last eight years have taught us anything, it is that political-military scenarios in the post-Cold War era will unfold “horizontally.” Situations will evolve over time with few clear-cut turning points, typically lapsing into a cyclical pattern that nonetheless features dramatic differences with each go-around. Think of our dealings with Saddam Hussein and Slobodan Milosevic and you’ll get the picture.

In horizontal scenarios, everything—and everyone—is free to evolve over time, meaning positions change, allies come and go, and definitions of the “real situation” abound. In this strategic environment, sizing and preparing one’s forces according to vertical scenarios isn’t just inappropriate; it is dangerous. It fosters a confidence in packaged solutions employing packaged forces armed with packaged assumptions—the 2-MTW standard in a nutshell—so that anything else you do with the forces reduces your readiness for those 2 MTWs.

Both the 2-MTW standard and the high-tech wannabes, with their nostalgia for "imminent" Soviet breakthroughs, suffer from slavish adherence to a collection of myths concerning the post-Cold War era. If we are ever going to move beyond their vertical scenarios to a better understanding of where the military fits in the globalization era, these myths must be punctured and discarded. Our top ten list of myths is:

10. There are far more conflicts and crises in the world after the Cold War! The number inflation on this one is unreal: suddenly every terrorist shoot-out and ten-person liberation movement is a “low intensity conflict.” When we count the significant conflicts and crises of the 1990s and compare them to those of the 1980s, however, we don’t find the stunning increase some analysts do. In the 1980s, we see one system-threatening conflict (the Iran-Iraq War), and in the 1990s we see two (Desert Storm, the Congo War—the latter a stretch). In the 1980s, we count 6 significant state-based conflicts and 24 internal conflicts, compared to 7 and 28, respectively, in the 1990s.[1] In sum, we’re looking at an overall increase of 6 cases, or fewer than one a year. Worth worrying about? Yes, since internal warfare these days involves failing states and generates lots of refugees. But a new world disorder? Hardly.

What political-military analysts should recognize in globalization is a remaking of the international economic order that rewards the most fit and devastates the least ready—in the same society. In advanced countries, the resulting conflict will be mostly political, but in some developing societies, these horizontal tensions will turn bloody in scattered instances. If you’re looking for a defining conflict, check out Indonesia’s disintegration following the Asian economic crisis.

9. The Soviet Bloc's collapse unleashed chaos!

The myth is that, with the stabilizing hand of the Soviets removed, conflicts have bloomed across the globe. This issue needs to be divided into its constituent parts: Soviet support to the Third World, Eastern Europe, and the former Soviet republics. In every instance the balance of the news is positive.

Looking at the old Third World, we view the collapse of Soviet assistance as an absolute good. Central America is certainly quieter for its absence, as is southern Africa as a whole, though Angola still burns. In the Middle East, Yemen is reunified, Qaddafi has stopped playing the Arab bad boy (for now), and the PLO lost Moscow's support. Granted, Soviet arms beneficiary Iraq reached a use-it-or-lose-it moment in 1990, and went for broke, but the same cannot be said for Syria. Afghanistan still stinks as a place to live, and Vietnam still goes its own way, but in sum, it's a pretty good deal for global order.

Some people insist on calling Eastern Europe a security vacuum, but the balance is very positive, with the obvious exception of the former Yugoslavia. But if Gorbachev had come to us 15 years ago and said he could arrange for the collapse of the Warsaw Pact, the peaceful reunification of Germany, and the absorption of several former satellite states into NATO, but the cost would be a bloody civil war in Yugoslavia . . . well, you get the idea. Moreover, Balkan experts will tell you that Yugoslavia's demise had nothing to do with the fall of the Soviets. It was a disaster waiting to happen once Tito passed away.

Finally, when looking at the former Soviet republics, we are sobered by events in Chechnya, the rest of the Caucasus, and Tajikistan, but still view the overall evolution as far more conflict free than anyone could have expected. Remember when we feared Russian invasions of the Baltic republics? Or Ukraine’s imminent Anschluss with Moscow? Or a wave of radical Islamic fundamentalism sweeping the “Stans?" (Okay, we are still watching that one.) Best yet, whatever violence has occurred here has been left to the Russians to figure out—unlike the Balkans.

8. We are swamped with failed states!

“Failed states” is another label that’s bandied about far too loosely. Reading some reports, you’d think they were spreading like wildfire across the planet. But there always have been failed states; we just never called them that. Instead, we used to call the Somozas and Siad Barrés “valued friend” and “trusted ally,” even as we helped to prop up their flimsy dictatorships. The Russians had a fancier phrase, “countries of socialist orientation,” but that was just Sovietese for flimsy communist dictatorships.

What defines a failed state in the globalization era is its failure to attract foreign investment. When none appears, or the leaderships steals it, the same feeble government that somehow muddled through the Cold War with superpower (or French) help now simply collapses. In the early 1990s, when the United States led what became U.N.-sanctioned interventions into Somalia and Haiti, there was optimistic talk of a new model—namely, the United Nations serving as midwife to these tortured societies’ slippery transition to stable economies and government. But the ill-supported United Nations proved a poor substitute for a superpower propping up a government with arms and military training.

Of the 36 countries in which internal conflicts occurred across the 1990s, the United States decided—after much angst—to intervene in only four: Somalia, Haiti, Bosnia, and Kosovo. So why did the decade seem so chock-full of U.S. interventions? Those four situations accounted for about half of all naval responses overseas and the bulk of the ship days involved in such operations.[2] To put it bluntly, advanced countries can safely ignore failed states (except maybe Indonesia), until “those damned Seattle people,” with their silly “values,” embarrass them.

7. Transnational actors are taking over the world!

This bugaboo must also be disaggregated to make sense of it. Starting with terrorists, the hype ignores historical data. According to the State Department’s annual report on terrorism, the phenomenon peaked in the second half of the 1980s, when it averaged 630 international attacks a year. Then the Soviet Bloc’s support system disappeared and so did much of the terrorism. Since 1989 terrorists have averaged 382 attacks per year—a 40% drop.[3]

Drug cartels and Mafia syndicates do not seek to disrupt global economic or political stability, but merely to generate profits. In effect, they desire macrostability within and among nation-states in order to create and exploit microinstabilities—i.e., illegal markets. These criminals are not interested in destabilizing or capturing political institutions, but in influencing them for their own ends. Granted, Colombia represents an odd turn, as the Marxist guerrillas there are now dependent on drug proceeds. But in general, the drug kingpins prefer to stay out of politics.

The same could be said for illegal aliens, who are looking for economic opportunity. Too rapid a migration can destabilize, but immigration is far from out of control in developed countries: seven out of eight immigrants now settled there arrived legally.[4] As for refugees displaced by conflicts, they are by-products of local chaos, and their "transnational" effects largely are limited to the next country over.

Finally, you have to wonder about the tendency of some national security strategists to lump transnational corporations (TNCs) in with this motley crew. TNCs not only represent the future of the global economy, they also account for the bulk of our 401ks. Anyway, it is a myth that TNCs act with indifference to their birth nations: every one has a home base, and almost all members of their boards come from that home. But the big point to remember is that TNCs invest overwhelmingly in countries where there is firm rule of law.

6. Technology proliferation is out of control!

This myth is sold in two sizes: rogue states and asymmetrical warriors. The funny thing is, in both instances, everyone usually ends up talking about the same sorry list of old Soviet-client survivors.

With the rogues, the biggest concern is that they are either buying or selling nuclear and missile technology. We also worry about them developing chemical and biological weapons, but that is not really high-tech anymore (nor have they made any of it work). Then again, their missiles aren’t state of the art either, as everything passed around this gang tends to use old Soviet technology.

Now, many of the “new security” types will try to sell you on the notion that missile proliferation is rampant among unspecified “potential adversaries” (their fear mongering would dissolve if they had to say who), but they’re really stretching here. Over the past decade more countries have just said no than yes.

Again, it is the four rogues who are proliferating (Libya, Iraq, Iran, and North Korea), and none is really doing very well at it. This quartet lives off of three suppliers who are in it for the bucks—Russia, China, and North Korea. U.S. diplomats are all over the three suppliers to join the civilized world of functioning economies, leaving it to the Pentagon to keep the pressure on the rogues. That does not sound like an out-of-control problem to us.

The “asymmetrical warriors” or “potential adversaries” are implied to exist in vast numbers, although few, if any, have ever been spotted in the wild. Nonetheless, we are told that all they need nowadays is a credit card and Internet access and voila—almost any dangerous technology can be picked up on e-Bay! This is the “silver bullet” concept taken to extremes: these warriors are presumed to deftly deny our access to conflicts by negating our high-tech advantage with their Radio Shack stuff. Meanwhile, we spend on military research and development alone more than what the rogues spend on their entire militaries.

5. China is the new Soviet Union!

China is not the Soviet Union. It remains a communist-governed country and retains major elements of a command economy, it mostly decollectivized its agriculture two decades ago and now sports a massive private sector. This mixed economy makes it unlikely that China will undertake anything like the single-minded military-industrial effort the Soviets made. Moreover, its defense technology is primitive and there are no signs it is embarking on anything like the Soviets’ high-level, concentrated scientific efforts.

China never presumed to offer an alternative world system and has no satellites, although it wants Taiwan back. Other than that myopic focus, it is fair to say that its relations with other Asian states are still evolving. China doesn’t aspire to conquer its neighbors and doesn’t pretend to spread communism, but it still worries about Western nations encroaching from the sea, as they did in the 19th century.

We kid ourselves when we cast China as this century’s Soviet menace. China desperately needs our direct investment for its skyrocketing energy requirements and our market for its low-tech exports.

4. Speed is everything in crisis response!

This concept is ingrained in our psyche because of our Cold War fears and the experience of Desert Shield. We have become addicted to speed of response because we are a reactive nation and have a long way to travel to any conflict. But here is where the world’s sole military superpower may be underestimating its power.

First, as the world’s Leviathan, what we bring to the table is not so much speed as the inevitability of our punishing power. The speed demons will counter that we have to rush in precisely because our foe will deny us the access we need to bring all that power to bear. This is an argument that strings a lot of little fears together into one big phobia:

- The Air Force fears we will be denied access to bases by cowed allies—an improbable scenario if we’re coming to defend them.

- The Marines fear we will have no choice but to perform forcible-entry amphibious landings because we don’t have any allies at all—cowering or not (tell that to the South Koreans).

- The Navy fears it won’t be able to operate in the close-in littoral in a timely manner and without losses, and will thus lose out to . . . the U.S. Air Force.

Two underlying realities render this debate moot: First, we are living in an age of horizontal scenarios where nothing really comes out of the blue anymore. If we don’t see the crisis coming, it is because we choose not to pay attention. Second, other than the unlikely cases involving extensive direct attacks on the United States, we are stuck with only surprise attacks by Iraq and North Korea (even China issued the required Notices to Mariners before testing missiles over Taiwanese waters in 1996). Sure, there could be other surprises, but none so system threatening.

Simply put, outside of Iraq or North Korea, administrations no longer have the writ to commit this country to large-scale violence without some sort of debate. The Cold War featured stand-offs with the Soviets (e.g., Berlin, Cuba) where the President was pretty much on his own, but those days—and that dire strategic environment—are long gone.

3. We cannot handle all these simultaneous crises!

At first glance, the Navy looks mighty busy across the 1990s, meaning three to five simultaneous naval responses across multiple theaters for much of the decade. Look deeper and you see a different picture: lengthy strings of sequential operations clustered around just Iraq, Somalia, Haiti, and Yugoslavia. Using traditional counting methods, these four situations account for roughly half of all naval responses in the decade. Almost all the rest were noncombatant evacuations or responses to natural disasters, except for brief shows of force off Taiwan and Korea.

How we interpret the strategic environment determines how we prepare to meet its challenges, and clearly, these “response clusters” represent serious change. During the Cold War we contained the Soviet Union along the entire breadth of Eurasia, concentrating our permanently stationed forces at such key points as the Fulda Gap and the Korean demilitarized zone. Meanwhile, the U.S. Navy balanced the Soviet Navy in the Mediterranean, Gulf, and Western Pacific. But the bipolar age, with its unified containment strategy, yielded to a more scattered and shifting sort of containment in the 1990s. In effect, we think the Somalia, Yugoslavia, Haiti and Iraq represent a new response category: drawn-out minicontainments designed to stabilize individuals regions.

2. We are doing more with less!

Just talking naval forces, ship numbers are down over the 1990s, while responses to situations—measured in the traditional manner—are up. Behind all this numerology (e.g., a noncombatant evacuation operation counts as much as a Desert Storm), however, lurks a persistent myth: naval forces are therefore grossly underfunded and suffering serious operational strain. Analysts pushing this argument are simply barking up the wrong tree.

Most of the stress on naval forces comes from the Persian Gulf and our near continuous operations there since 1979. The Pacific, meanwhile, has been quiet—in terms of responses to situations—for the last quarter century. Both the Mediterranean and the Caribbean were reasonably busy in the 1990s, but like the Gulf, the bulk of the activity involved one lengthy situation each (Yugoslavia and Haiti). The numerologists see response totals as way up, but in reality the Navy spent the 1990s focused on just those four big situations. And it was not alone: Navy-only responses dropped from 74% in the 1970s to 35% in the 1990s, the rest being joint or combined.

Amazingly, despite being tied down in the Gulf and working the rest of the world with fewer ships, the U.S. Navy is breaking neither operational nor personnel tempo. All of the responses are being conducted by regularly deploying ships (Desert Storm is the great exception). Ship schedules are definitely disrupted and some port calls missed. Speed of advance for some transits has been accelerated, but turnaround ratios for carriers have lengthened. In sum, we have not needed to deploy ships ahead of schedule, nor are we short a carrier when we really need one.

In sum, the U.S. military is handling the current response load with dexterity, with the exception of high-demand/low-density assets (e.g., Navy EA-6Bs, Army civil affairs specialists). But that particular problem only highlights the illogic of centering all our strategic planning on the abstraction known as the 2-MTW standard.

1. All we can plan for is complete uncertainty!

Trying to capture global change by looking at U.S. military history is like looking through the wrong end of a telescope: our interventions are but a thin slice of a much larger reality, most of which is wrapped up in globalization. Moreover, the military deals mostly with the seamy underbelly of an otherwise pretty good world, which gives it a peculiar perspective. The biggest global events of the past eight years were the explosive rise of the Internet and international financial flows, the Asian economic crisis, and last year’s Y2K drill, none of which involved the defense community in any significant way. Instead, the military got stuck largely with watching the store on Iraq, Somalia, Haiti, and Yugoslavia—the losers of the world.

Some like to describe the 1990s as a time of chaos, identifying uncertainty as our new foe. Many take the Clinton administration to task for merely reacting to events and having no coherent foreign policy, as if that were different from previous administrations. But anyone who lived through the tense and constant confrontations with the Soviet Union should be grateful for this sort of “uncertainty.”

When we look over these years, we detect a clear routinization of what used to be legitimately described as crisis response, not some growth of uncertainty. For the Navy, its presence in the Gulf has become routine. Its drug patrols has become routine. Its presence in the Western Pacific is stabilizing as far as everyone but the Chinese are concerned, but this has practically nothing to do with “responses” since the end of the Vietnam War—thus it is routine. Even last decade’s clustered responses in the eastern Mediterranean assumed a familiar routine, dragging on for years until Milosevic finally fell. As for Africa, we have seen this nation and its leadership shy away, passing up lots of opportunities to intervene.

But was there any grand strategy that linked together all these choices? Not really. And maybe that’s what irks us political-military strategists most: as this circus parade known as globalization winds it ways around the planet, the military is mostly left to clean up what the elephants of the advanced world would just as soon leave behind and forget. As such, we think it is relatively easy to predict what the U.S. military will be called upon to do over the next ten years: several of these minicontainments plus the usual scattering of minor responses.

Moving Naval Strategic Planning Beyond Mythology

The world is not a more dangerous place after the Cold War. Chaos, it turns out, is not as fungible as we once thought, and uncertainty, like all politics, is local. But adjusting to this brave new world does not necessarily equate to a reduced role for the military in U.S. foreign policy, especially naval forces. Rather, it means we now have a broader and more flexible basis on which to plan. The new national military strategy clearly lies somewhere between our recent extremes—neither matching the Soviet Union nor policing the Soviet-less world.

Finding that middle ground means moving away from the abstractions embodied in the 2-MTW standard. Simply put, we have gathered enough data points across the 1990s to plot out this decade’s navy, if not the navy after next:

- It is a naval force that lives in, and deals with, the present world, one that is always likely to afford the United States several opportunities for lengthy, minicontainment operations. We will not address all of them, but pick and choose as we see fit, with the key determining factor being that situation’s potential disruption of the global economy.

- This force is comfortable with uncertainty, because these response clusters will come and go, meaning multiple operational centers of gravity that shift with time.

- This force plays an important, if largely background role in enabling globalization’s continued advance, especially in developing Asia, by embodying the closest thing the world has to a true Leviathan—the undeterrable, always familiar military giant.

- This navy lacks any real peers and hence can confidently plan for the future, which means staying just enough ahead on technology to discourage the rest of the world from trying to keep up.

- Above all, this naval service should take good care of its ships, aircraft and people, without using them up and exhausting itself. Outside the Persian Gulf, the world does not need it that much, and when it does, we will have warning time.

The Navy has moved far enough beyond the Cold War to understand its “new” role in international stability. If it seems familiar, it is because the base of our operations has remained essentially unchanged, even as the superstructure of the Cold War’s bipolarity came and went. The U.S. Navy works the watery seam that both divides and links the planet’s northern and southern economic zones. As these huge civilizations and individual societies bump against one another in the tectonic inevitability that is economic globalization, U.S. naval forces will play an important stabilizing role within this country’s overall foreign policy—that of a mobile, sea-based containment force.

Response clusters such as Iraq and Yugoslavia will remain a stubborn facet of the future international security environment, representing the essence of the naval forces’ mission. As such, it is time to end our dependency on abstract planning measures such as the 2-MTW standard, come to grips with the world as we have come to know it, and do right by our sailors and Marines.

[1] The 1980s conflicts (31) are Guatemala, El Salvador, Nicaragua, Panama, Colombia, Peru, Grenada, Falklands, Northern Ireland, Poland, Turkey-Kurds, Nagorno-Karabakh, Western Sahara, Libya, Sudan, Chad, Ethiopia, Uganda, Angola, Mozambique, Lebanon, Syria, Israel, Iran-Iraq, Sri Lanka, Burma, Afghanistan, Kashmir, Cambodia, Philippines, and China-Vietnam. The 1990s conflicts (37) are Mexico (Chiapas), Guatemala, El Salvador, Colombia, Peru-Ecuador, Peru, Haiti, Northern Ireland, Former Yugoslavia, Turkey-Kurds, Georgia, Chechnya, Nagorno-Karabakh, Algeria, Chad, Sierra Leone, Sudan, Liberia, Zaire, Somalia, Ethiopia-Eritrea, Burundi, Rwanda, Angola, Mozambique, Lebanon-Israel, Yemen, Iraq, Tajikistan, Sri Lanka, Afghanistan, Kashmir, Cambodia, Burma, China-Taiwan, Indonesia, and East Timor.

[2] Somalia accounted for seven responses, Haiti for six, Bosnia/Kosovo for 12 and Iraq for 13. That’s 38 total, or almost half of the decade’s total of 81 naval responses.

[3] Find this report at <www.state.gov/www/global/terrorism/1999report>.

[4] Demetrios G. Papademetriou, “Migration: Think Again,” Foreign Policy, no. 109 (Winter 1997-98), p. 16.

Dr. Barnett is a professor at the U.S. Naval War College, serving as a senior strategic researcher in the Decision Strategies Department of the Center for Naval Warfare Studies. Dr. Gaffney is a research manager at The CNA Corporation, serving as Team Leader in the Center for Strategic Studies. Professor Bradd C. Hayes provided valuable feedback.

Sunday, August 8, 2010 at 12:03AM

Sunday, August 8, 2010 at 12:03AM  Vice Adm. Dennis V. McGinn (center), Deputy Chief of Naval Operations for Warfare Requirements and Programs presents Prof. Tom Barnett (left) with the Naval Institute's 'Author of the Year' award as Rear Adm. Rodney P. Rempt (right), Naval War College President looks on during a ceremony in Annapolis, MD.

Vice Adm. Dennis V. McGinn (center), Deputy Chief of Naval Operations for Warfare Requirements and Programs presents Prof. Tom Barnett (left) with the Naval Institute's 'Author of the Year' award as Rear Adm. Rodney P. Rempt (right), Naval War College President looks on during a ceremony in Annapolis, MD.