by Thomas P.M. Barnett

GOOD magazine, May/June 2008, pp. 58-65

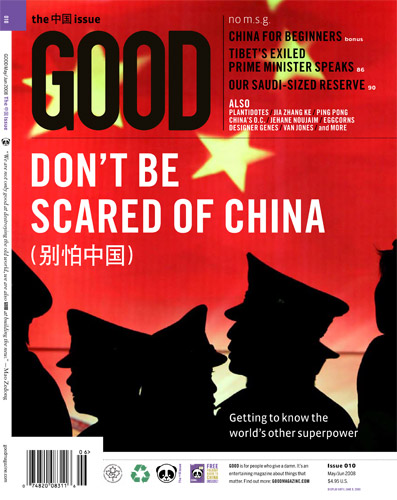

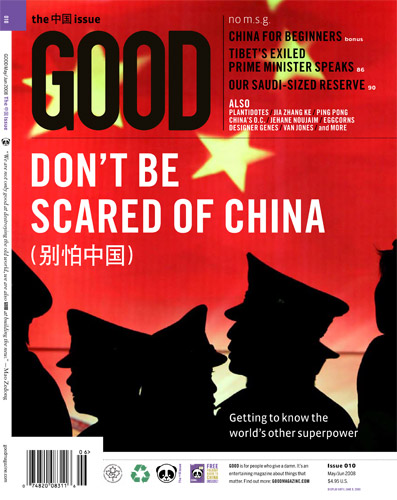

Don’t be scared of China—the country is perfectly positioned to be our most powerful ally (lack of democracy notwithstanding, of course). But if there is anything to worry about, it’s not China’s massive military; it’s the economy, stupid.

Why China Matters To You:

10.

Because Nixon went to China and your world was born.

When President Richard Nixon reopened diplomatic ties with Mao Zedong's communist China in 1972, he enabled the most profound global economic dynamic of the last half century: China's historic reemergence as a worldwide market force. Nothing shapes your world today more than China's rise, and nothing will shape our planet's future more--for good or ill--than China's ongoing trajectory.

After centuries of relative isolation, China’s rapid reintegration into the global economy transformed globalization from its narrow Cold War-era base (the West) to its current “majority” status, whereby two-thirds of humanity now enjoys deep and growing connectivity with international markets and the remaining third works toward it. China’s decision to rejoin the world was globalization’s tipping point, meaning—absent global war—there’s no turning back now, only adaptation.

If Nixon opened the door, then Mao’s successor Deng Xiaoping led the Chinese people through it. Unlike Mikhail Gorbachev, Deng chose wisely: By tackling economic freedom before political liberalization, Deng kept China stable during its tenuous first years of market reform. Although Deng is correctly labeled an autocrat (he ordered the bloody suppression of the Tiananmen Square democracy protests in 1989), he is also correctly identified as a modernizer who unleashed a generation’s immense creativity.

Many from that generation will tell you that, before Tiananmen, they felt freedom was “90 percent political and 10 percent economic,” but after Deng’s crackdown, they concluded—somewhat harshly—that real freedom was “90 percent economic and 10 percent political.” In other words, they decided that markets were the first, best instruments for generating positive change in China.

A grand bargain was struck: Deng won military support for further market reforms so long as a lid was kept on political change, and the army was afforded enough of a budget to modernize. The Party would remain supreme, but state involvement in the economy would shrink and private business would be encouraged along with investment from, and trade with, the outside world.

China has experienced incredible economic growth ever since, increasing its gross domestic product annually by almost 10 percent—as fast as you dare expand. But China is also nowhere near becoming a democracy, and its achievement scares nations around the world—and excites others—because it suggests that you can rapidly embrace globalization, achieve great income growth, and remain a single-party state by following the so-called China model.

9.

Because China may be an ancient civilization, but it's a young society that's growing up very quickly--and unevenly.

China's modernization strategy included slowing population growth through the “one-child policy.” Yet China remains huge: 1.3 billion souls crammed into a country no larger than our own. So if you think we’ve added quite a few Hispanics in the last couple of decades, imagine inviting everyone in the Western Hemisphere and half of Africa to come live inside the United States, because that would give us China’s crowded mix of rich and poor.

Given China’s traditions, the one-child policy favors males over females; the latter are too often aborted or offered up for international adoption. (Disclosure: My fourth child originally hailed from Jiangxi province.) The build-up of males has led some Western demographers to worry that over time, China will inevitably become militarily aggressive—how else to distract all those frustrated young men? But this fear is overblown, as is evidenced by trends in the rest of Asia, where, for example, similarly frustrated South Korean males simply go abroad and, you know, marry a broad in places like Vietnam or Thailand. Bottom line? Desire wins out.

The more profound legacy of the one-child policy is that China will grow very old, very fast. Right now the country enjoys a demographic sweet spot: plenty of workers supporting relatively few children or elders. But once you restrict the baby supply, the population as a whole moves up collectively in age, meaning that China will rapidly progress toward the “Florida mark” (20 percent of the population above age 65) in just two decades. The United States will hit Florida around the same time. If America, in all its wealth, is struggling with that profound shift, how much harder do you think it will be for China, weighed down by hundreds of millions of impoverished peasants?

Here’s one thing to remember when anyone tries to sell you on China running the world someday soon: that China will get very old before it gets truly rich, something the world has never witnessed before. What history tells us is this: Aging populations are not aggressive populations.

8.

Because China's transformation echoes much of America's past: not only the good, but plenty of the bad, and the ugly too.

Impossible, you say. Ruled by communists, China’s civilization bears no resemblance to our own.

But China’s true “communist” period was just three decades out of a 5,000-year history, the rest of which featured a social bent toward markets in general (the Chinese are inveterate gamblers, for example) and past periods of serious global trade connectivity (recall the Silk Road of yore). Add in the strong focus on family ties and a deep spiritual history that has long featured free competition among various faiths and we’re not exactly talking about some brother from another planet.

So forget trying to figure out today’s China through its own history, an endless cycle of disintegrating peace and integrating war. Think about it this way: Right now, China is somewhere in the historical vicinity of “rising America” circa 1880—absent democracy, of course. Once you realize that, then depending on where you go around China, you can locate yourself somewhere in the last 125 years of America’s own ascendancy.

Some examples: Foreign policy-wise, you’re looking at a mild-mannered Teddy Roosevelt: China’s military stick is getting bigger, but it still prefers to speak softly, mostly threatening small island nations (read: Taiwan) off its coast.

The nation is likewise undergoing a construction and investment boom that’s right out of 1920s America, and frankly, that should give pause to anyone concerned with global economic stability. China’s banking and financial industries are about as regulated as ours were prior to the Great Crash of 1929. But there’s no sign of a slowdown. Shanghai already has 4,000 skyscrapers—twice as many as New York—and plans another thousand.

Check out China’s space program, which just put its first man in orbit. Beijing now speaks openly of repeating our 1960s quest for the moon. Groovy! Let me just raise my glass of Tang in salute and wonder why Americans aren’t on Mars yet. Speaking of which, there’s also a sexual revolution brewing, with China’s urban youth taking one great leap forward from Father Knows Best to Sex and the City. This revolution won’t be televised, but it’s being compulsively blogged.

Corruption-wise, Beijing remains stuck somewhere prior to the Progressive Era of late-19th-century America, and that’s no good. China’s political system needs to be able to process all this social and economic pressure with more flexibility. Citizens are simply growing angrier and more demanding with each passing year. China’s legal system also needs to clean up its act, because the more China’s economy opens up, the more the global business community is going to demand greater transparency and better avenues for legal redress. Corruption already consumes upwards of 5 percent of China’s gross domestic product. In a “flat world” of economic hypercompetitiveness, such inefficiency eventually costs too much.

7.

Because China's rapid and deep integration into manufacturing means that Chinese products permeate your life--at some risk.

Globalization tends to integrate trade by disintegrating global supply chains. By breaking up these chains, globalization spreads various segments of production and assembly across those economies that offer the cheapest labor for each particular stage. China has deftly inserted itself into a long list of these chains, becoming the final assembler of note in toys, cell phones, CD players, computers, and auto parts, to name but a few. By doing so, China has consolidated much of Asia’s previous trade surpluses with America into its own burgeoning bilateral trade with the United States. So when you hear about America’s huge trade deficit with China, bear in mind that it’s the same huge trade deficit we’ve long had with Asia as a whole.

Also be aware that this figure hides a lot of complexity. Foreign corporations control the majority (approximately two-thirds) of this production for export. American companies in particular dominate China’s U.S.-export sector, meaning it’s basically our companies renting Chinese labor and keeping much of the profit. The Chinese export that sells for hundreds of dollars in America nets only tens of dollars for the Chinese economy. That’s how Wal-Mart, the single biggest source for Chinese exports in the world, keeps its prices so low. So if you think Western companies are exploiting cheap Chinese labor, then understand that you’re a prime beneficiary.

Naturally, China’s deep penetration of the U.S. market has raised product-safety issues. Any economy that is growing as fast as China’s cuts plenty of corners. But realize that China learns by scandals just as America did over the past century. Frankly, the best crises are the ones you actually hear about, because that means the international press got ahold of them, and those already affected or at risk will get the information they need to protect themselves. Once tracked back to China, Beijing is put on public notice that whatever laxness exists simply cannot be tolerated anymore, with threats of quarantine, bans on exports, cessation of investment flows, and so on.

A generation ago, such threats would elicit yawns from China’s ruling elite, but now, with the Communist Party’s legitimacy riding on economic expansion, they’re taken with the utmost seriousness. In short, China’s government is starting to act more like a business which recognizes that its reputation is often its most important asset, because fierce competition means that today’s mistake allows somebody else to steal your customers by the start of business tomorrow.

6.

Because China's demand for resources is altering global markets in ways both profound and perverse.

China’s explosive economic growth forces it to suck in resources from all over the world. As James Kynge, a longtime China-watcher, notes in his recent book China Shakes the World, “China’s endowments are deeply lopsided.” Blessed with too many people, China is short on just about everything else: arable land, water, energy, and raw materials of all sorts. Thus, the only way China manages to serve as globalization’s “manufacturing floor” is to become a leading global importer of virtually any commodity you can name, from cement and copper to oil and gas.

While there’s hardly anything wrong about that, China’s insatiable demand for resources likewise drives Beijing to actively court pariah states and “rogue regimes” while the West tries to isolate the same regimes with economic sanctions. Take China’s relationship with Iran: While American diplomats work night and day to level even harsher sanctions to slow down Tehran’s reach for the bomb, China quietly edges out Japan as Iran’s major energy investor, sweetening the deal by reselling it some of that fabulous high-tech military hardware the Chinese military imports from Israel—hardware which then turns up in southern Lebanon in the hands of Hezbollah.

On the face of it, that constitutes obstructionism on China’s part, as if it’s trying to prevent the global community from cracking down on bad behavior. But the inescapable truth is that China’s scramble to find resources means it has to cut deals with anybody, no matter their disreputable record. So while Sudan’s government engages in what many Western states consider to be “ethnic cleansing” or genocide in its Darfur region, China is more than happy to invest heavily in Sudan’s oil industry while supplying the Sudanese government with weapons. Do that long enough and you’ll have Hollywood stars galore decrying your hoped-for coming-out party as the “genocide Olympics.”

But the longer-term danger is this: China is getting awfully dependent on a lot of unstable countries without having the global military footprint of a great power—you know, like somebody building a very large house made of straw, nowhere near a fire station. When bad things happen—like, say, that one afternoon nine Chinese oil-rig workers were killed by rebels in eastern Ethiopia—China can’t respond like a military power you should fear, because it needs that oil. Once that reality sinks in with local bad actors, expect them to start squeezing Beijing for their own slice of protection money. You know that Thomas Friedman bit about America funding both sides of the “war on terror”? Well, this is how that sort of thing starts.

Today, China might get by simply by buying off every dictator it can. But that won’t work in a future world defined by hyperconnectivity, where everyone can witness the human implications of China’s deal-making. Nor will it work in a future world defined by hyperinterdependency, a world China is creating—whether it realizes it or not.

5.

Because the panda "huggers" versus "sluggers" debate is a lot of hot air--until Washington scares Beijing into raising your mortgage interest rate five points overnight.

I’m considered a “panda hugger,” someone who rationalizes China’s current lack of democracy and argues that, despite all its selfish behavior, China should be considered by America more as a potential ally than a downstream threat. Being an economic determinist (I taught Marxism at Harvard in another life), I believe economics shapes politics more than the other way around. Thus, I tend to be patient when I see an autocratic regime marketizing its economy, especially when the economy opens up to globalization’s networks.

So when I draw up a list of regimes I’d like to see forcibly changed by the global community, China’s nowhere near the “to do” range. That doesn’t mean I want Washington to forgo pushing Beijing’s leaders in the direction of increasing political freedom and transparency, it just means that I have more faith in the transformative power of markets than others do, so I don’t argue for picking fights with China on that score when I think there are so many other, more urgent situations around the planet today that we could collectively address.

“Panda sluggers” refers to those politicians, writers, and activists who make just the opposite argument: China has had plenty of time to change politically in a manner commensurate with its embrace of markets and globalization. If Beijing’s ruling elite has managed to keep such a firm grip on political power, then maybe it’s really cracked the code on “authoritarian capitalism,” meaning we’re looking at an inherently antagonistic model of development. If so, America had better wake up to that reality and start combating China’s “soft power” influence-peddling around the world.

This view dovetails with trade protectionists who say that Washington must confront Beijing over its unfair trade practices and defense hawks who say similar things over China’s rising military spending. My counterargument? When America was a rising power around the beginning of the last century, we were highly protectionist. Now that we’re advanced, we’d like everybody else to follow our example. Fair? All things being equal, yes. But all things aren’t equal when you’re trying to catch up, the way China is today. I say, if you talk them into becoming capitalists, then you have to live with the consequences and be patient.

What concerns me most about this ongoing debate is the potential for the perfect triggering crisis to come along and decisively shift public opinion in favor of the “slugger” position, launching America down some path of economic retaliation against and/or military confrontation with China. Obvious security situations spring to mind, such as North Korea’s nuclear program, Iran’s nuclear program, or some significant U.S. military intervention in Pakistan—a longtime strategic ally of China.

But a more likely trigger is an extended economic downturn in the United States, or a financial panic in China following the bursting of some stock market bubble. If seriously threatened, might China decide to divest itself of U.S. currency—China currently holds $1.4 trillion in U.S. dollar reserves—sending the value of the dollar into a tailspin? No one knows for sure, but intelligent observers realize that, as former treasury secretary Lawrence Summers has put it, there basically exists a financial “balance of terror” between our two economies, meaning that when either of us pulls the economic trigger, we may well both end up with fatal wounds.

4.

Because as China builds out its infrastructure, it can set a good or a bad example to developing economies struggling to deal with fragile environments.

American businesses face a key decision: dive into China’s dynamic markets or risk missing out on their coming wave of innovation. Nowhere is this more true than in infrastructure development, which is expanding like gangbusters in China right now and will continue to do so for the next couple of decades. Good example: China is building freeways like crazy. In about 20 years, it’ll have roughly 50,000 miles of them—the equivalent of our interstate system.

In that time, the world will spend $10 trillion for infrastructure development in energy ($6 trillion) and water ($4 trillion). Most will happen inside China and India at a pace not witnessed on this planet since America spread its network westward following our Civil War. Naturally, environmentalists are worried. If China replicates our resource-intensive style of growth throughout its economy, there will be no end to its pollution and carbon emissions. If you’ve spent any time in China, you know what I’m talking about: acrid-tasting air that the U.N. estimates is responsible for the premature death of 400,000 Chinese a year. Now add in the four times as many cars and trucks that will be on Chinese roads in 20 years’ time, along with far more urbanization and industrialization, and tell me if that sounds sustainable.

But guess what? The Chinese themselves aren’t exactly clueless on the subject. After all, they live there. So I’m betting—and I admit this is a bet—that the Chinese, along with the Indians and emerging markets elsewhere, will be smarter than that. Not because they want to be, but because they’re forced to be. These rising economies will have to zig where we zagged, and how they zig will be important, not just for the “advanced” West, but for all those emerging markets to come in places like Africa.

3.

Because China is globalization's general contractor: always happy to take the job and your money, but hard to get on the phone once you discover problems.

Globalization now impinges on the most traditional, off-the-grid societies in the world. Not surprisingly, there’s going to be plenty of cultural blowback triggered by that process, and some of it is going to come our way in the form of transnational terrorism—just as it did on 9/11.

For America to win a long war against radical extremism, we need to make globalization truly global by integrating the one-third of humanity whose noses remain pressed to the glass, wondering when they’ll be let in to the party. That’s labor-intensive, and American workers price out far too high. Yes, we must be significantly involved, but it’s not going to be Americans—much less Europeans—who do the heavy lifting. No, it’s going to be those longtime frontier laborers of the global economy—the Chinese and other Asians. The highly networked Chinese have shown up like clockwork at every frontier globalization has ever created. Currently, more than a million Chinese nationals have turned up in Africa alone, engaging in what I call preemptive nation-building. It’s great that China has triggered a commodities boom over much of Africa. God knows those economies can use all the help they can get. But the longer it looks like China is just there for the raw materials, the more Africans are going to catch on to the fact that—for now—the Chinese aren’t doing any more for the continent’s long-term development than the European colonial powers did decades ago.

But China needs our help, too. As the Chinese become increasingly dependent on resources drawn from unstable regions—by 2020, roughly 70 percent of China’s oil imports will be from the Middle East—the country must continue leveraging U.S. military power. Otherwise, it’ll be left unduly subsidizing weak or corrupt regimes, with China’s economic connectivity put at risk by local warlords, chronic insurgencies, and radical extremists bent on driving out globalization’s networks. If America can’t afford to maintain global security on its own, and China can’t afford to replace our effort on its own, then a strategic alliance makes eminent sense.

2.

Because China will not be our biggest future enemy but our most important ally.

A significant portion of our national-security establishment wants desperately to cast China as an inevitable long-term threat. Why? Part of it is simply habit, as most who argue this line spent the bulk of their professional lives in the Cold War and just can’t imagine a world that doesn’t feature a superpower rivalry. For those who need to fill that hole, China is the best show in town, because its military buildup allows these hawks to argue that America must buy and maintain a huge, high-tech military force for potential large-scale war with the Chinese.

My counter is this: China’s military buildup is not historically odd. America did the same as it became a global economic power in the late decades of the 19th century. Remember Teddy Roosevelt and the Great White Fleet? It’s the same logic we see with China today.

But won't events put China and the United States at odds—say, over the strategic issues of fostering stability in the Persian Gulf? Hardly. Right now the United States imports only about one-tenth of the Persian Gulf’s oil exports, with the vast bulk heading east to Asia. Frankly, there’s no sense in the strategic equation “American blood (spilled) for Chinese oil (imports secured).” As China’s oil imports skyrocket in coming years, unlike ours, do you think that’s a politically sustainable situation?

My larger, more long-term fear is that by keeping China our preferred threat, we deny ourselves access to its significant military manpower and growing budget. With Europe and Japan both aging dramatically and China’s strategic interests ballooning in unstable regions, this makes no sense. Better to lock in China as soon as possible as the land-power anchor of an East-Asian version of NATO. The sooner we achieve that, along with Korea’s reunification, the sooner we can draw down our military in the region and better employ it in hotter spots around the world, eventually with Chinese (and Indian) troops helping out.

What would a strategic alliance with China look like? It won’t come as some “grand bargain” achieved in a single summit, but rather a long-term buildup of trust through coalition operations. Asia is an obvious focal point for such cooperation, but a complex one. Far better in the short run would be to create a strategic dialogue between the Pentagon’s nascent Africa Command and the Chinese military regarding joint peacekeeping and humanitarian operations in Africa. By focusing on that relatively clean slate, America and China could come together to explore what our military alliance could ultimately entail.

1.

Because we're less than five years from a new generation of Chinese leaders with whom a far stronger relationship may well be built.

China is on the verge of a generational leadership change that will profoundly shape its emergence as a global power over the next decade. America should take advantage of this new group’s eagerness to play an actively constructive role in international affairs.

To make clear how this would work, here’s a quick primer on the generations of Chinese leaders since 1949: Mao personified the first generation, Deng the second. Deng was followed by a third generation fronted by Jiang Zemin, China’s president and party boss across the 1990s. What’s important to note about the third generation is that this cohort was largely educated in the Soviet Union during the 1950s. The technocratic flavor of that formative experience emboldened these leaders to extend Deng’s economic reforms far deeper into Chinese society, even as the leaders steadfastly refused political liberalization.

That brings us to the current, or fourth, generation of leaders, represented by President Hu Jintao and Premier Wen Jiabao, a risk-avoiding pair who have been quietly at the helm of “peacefully rising” China since 2002. Internally, their focus has been on harmonizing the huge imbalance between the booming coastal provinces and the left-behind rural poor of the interior.

Since 9/11, China has been almost invisible in international security affairs, essentially free riding on America’s vigorous prosecution of both radical Islam’s global insurgency and the so-called Axis of Evil, despite being a potentially key player. After all, China has long stood as North Korea’s patron and now emerges as a dynamic investor for energy and raw-materials providers throughout the Middle East and Africa.

But understand this: China’s fourth-generation leaders did not travel abroad in the 1960s for their college education, trapped as they were by the Cultural Revolution. So it’s hardly a surprise that these homebodies have proven reticent to step out internationally. But that’s changing as China’s fifth-generation leaders-in-waiting step into senior positions of power. Starting in the late 1970s, many of them were educated right here in the United States—the birthplace of today’s market-driven globalization. All but penciled in for future top slots last fall at the Communist Party’s supreme gathering, this group has already begun its years-long transition to rule, slated to begin officially in 2012. Increasingly, China’s next leadership generation speaks openly of the nation’s achievement of great power status.

How America engages China’s emerging elite in coming years could well determine—for good or ill—the lasting contours of the most important bilateral relationship of the 21st century. The scariest aspect to this relationship right now is that America’s economic interdependency with China vastly outweighs the two nations’ political and, more important, military connectivity. Bind America and China together, and globalization cannot be derailed. But set them persistently at odds, and that’s a recipe for unacceptable danger.

Thursday, September 16, 2010 at 12:09AM

Thursday, September 16, 2010 at 12:09AM

China,

China,  EU,

EU,  auto industry,

auto industry,  global economy | in

global economy | in  Citation Post |

Citation Post |  Email Article |

Email Article |  Permalink |

Permalink |  Print Article

Print Article