Economist Technology Quarterly story on a bugaboo I've been hearing about since the early 1990s: anti-ship cruise missiles will rule the naval warfare landscape of tomorrow.

I've always been fuzzy on how this would work. Great power navies firing missile at each other and somehow not triggering unwanted escalation toward nuclear exchanges? Or maybe it's regional rogues who nail a great-power ship or two and, on that basis, win the larger conflict? Or the lucky shot by terrorists that changes the global correlation of forces?

Every scenario I've ever come across has this fait accompli logic: we're denied "access" to some fight because our ships can't get in close out of fear of anti-ship missiles and then the baddies win the entire day--lightning quick.

If this sounds an awful lot like the Taiwan scenario, you've been paying attention.

Then there's the whole closing-the-Straits-of-X scenarios, where cruise missiles shut down major lanes of global trade for days/weeks/months on end, but these get too fantastic almost from the start. If it takes 10 or more subsonic missiles to sink a well-defensed warship (a standard cited in the piece), then imagine how many it would take to sinker a big-ass tanker.

Then there's the transnational swarmers easily defeating a nation-state foe, with the big example being Hezbollah firing a subsonic missile in 2006 at an Israeli corvette and killing four sailors. This is held up as a stellar example of "poor man's way" of sea power (a STRATFOR comment that reflects that for-profit company's typically clever fear-mongering).

In this way, we are meant to be impressed to Iran's growing seapower of fast boats and so on.

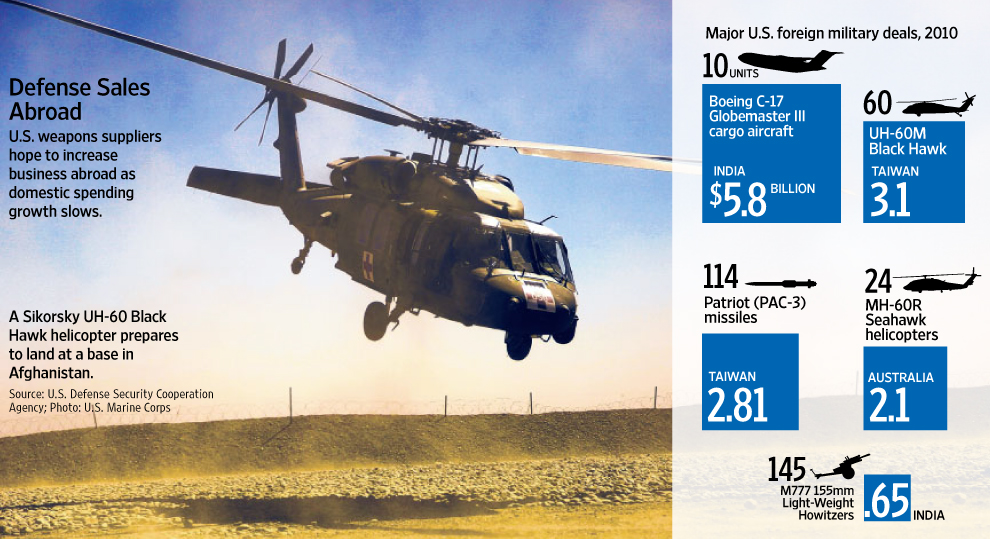

But whenever I read these scary reports, I'm always impressed by the fact that all the relevant technology is being developed by great powers and then exporting to medium sized powers, who buy the weapons primarily out of fear of the same great powers. So in the end, we've got a lot of navies getting all excited--in weird isolation from the world around them--about the possibility that they're going to get to sink each other's ships like crazy in coming, dreamt-of naval battles.

Oh, and then there's the Iranians shutting down Hormuz or Hezbollah ruling . . . I dunno, the Eastern Med for 20 mins some afternoon.

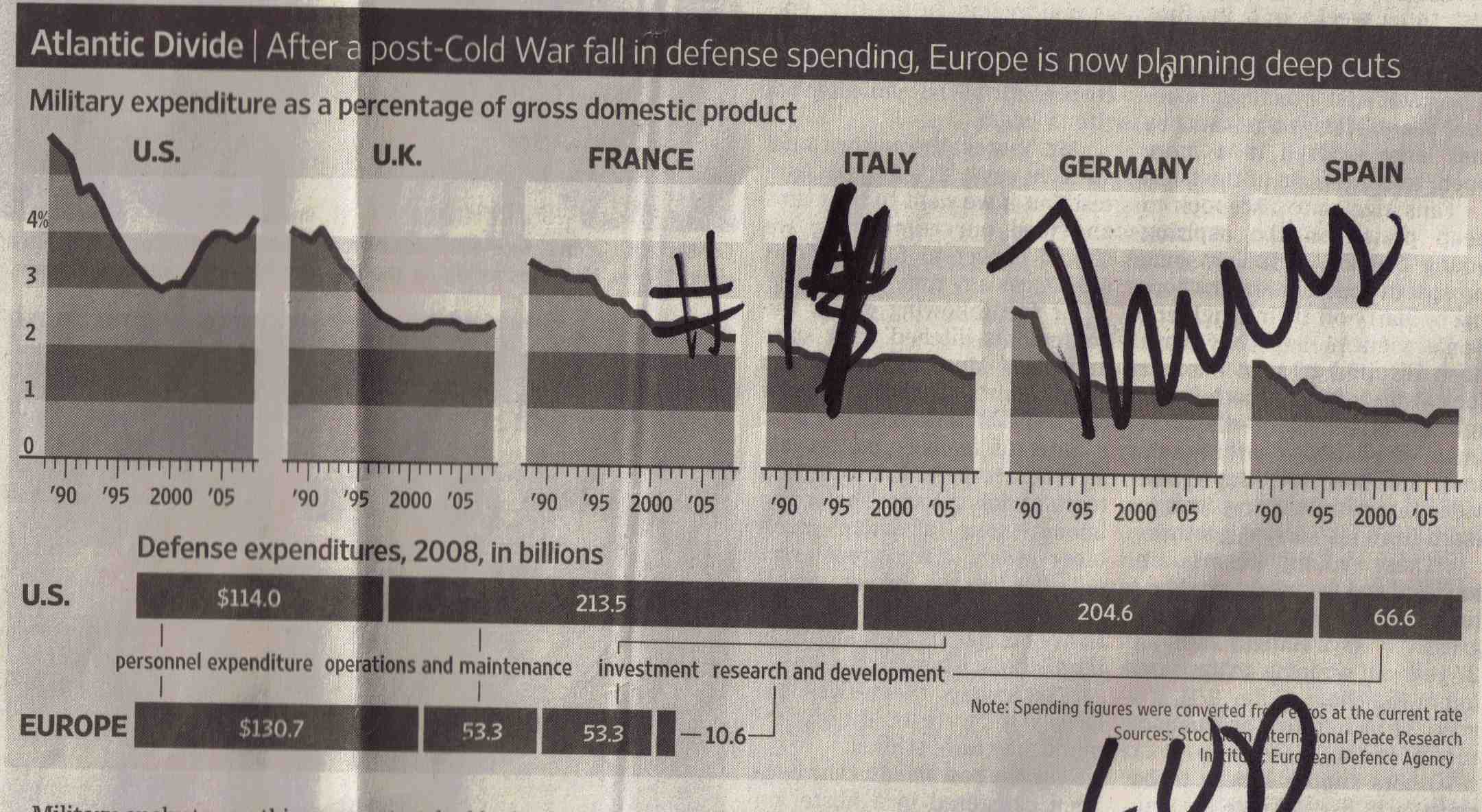

So you're left with globalization's major-economy navies worrying about the residual possibilities of great-power warfare (the 65 year moratorium looks stronger than ever), medium powers worrying about great powers, great powers worrying about "poor man's" sea-power-seeking navies built around fast boats, and that old lucky-shot-by-terrorists scenario. And all this is meant to scare me into what, exactly?

I guess it should scare me into stop building my fleet primarily around huge platforms and start moving toward swarm mentalities.

Or I can continue building tricked-out capital ships and have my industrial complex sell missiles abroad and then fret about the chances that those trends will eventually collide--undoubtedly with Trafalgar-like, world-empire-shattering impact. US Navy ships are so easy to sink, that's why they drop like flies all the time.

Is it just me? Or does naval thinking seemed trapped in some strange land of yesteryear? I mean, how far back do we have to go to find significant naval battles to justify this seemingly brain-dead thinking? When you get down to citing Iran and Hezbollah in your article on "peril on the sea," doesn't it seem like the conversation has gone stale? Here we live though the great age of globalization, and the state of imaginative thinking in naval strategy is running around with your hair on fire over cruise missiles.

Ah, but I neglect the great Sino-American battles to come. Those should play well on major financial markets.

Then again, I am so naive.

Sunday, September 5, 2010 at 12:04AM

Sunday, September 5, 2010 at 12:04AM

Middle East,

Middle East,  US foreign policy,

US foreign policy,  security | in

security | in  Citation Post |

Citation Post |  Email Article |

Email Article |  Permalink |

Permalink |  Print Article

Print Article