CSPAN viewers: here's where to find me

Sunday, December 24, 2023 at 6:00PM

Sunday, December 24, 2023 at 6:00PM This is my old site.

The site for the book is https://www.americasnewmap.com

The site for my ongoing writing is on Substack is thomaspmbarnett.substack.com

Sunday, December 24, 2023 at 6:00PM

Sunday, December 24, 2023 at 6:00PM This is my old site.

The site for the book is https://www.americasnewmap.com

The site for my ongoing writing is on Substack is thomaspmbarnett.substack.com

Thursday, March 9, 2023 at 8:28AM

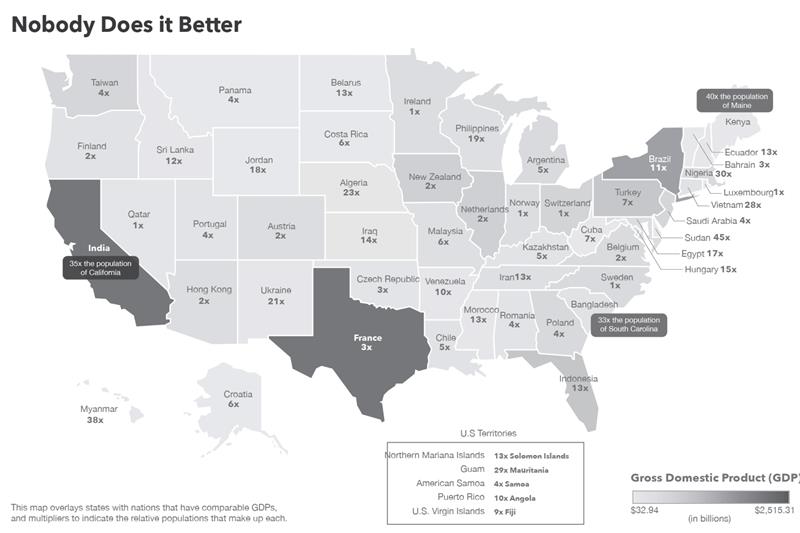

Thursday, March 9, 2023 at 8:28AM The book, with its fabulous illustrations (52) and data visualizations (24) targets a non-expert and expert audience alike.

Visit the website americasnewmap.com

Pre-order the book now at Amazon and Barnes & Noble.

GLOBALIZATION'S THROUGHLINES: RESTORING US GLOBAL LEADERSHIP IN A TURBULENT ERA <PREFACE>

Frankenstein’s Monster: Coming to Grips with Our Most Powerful Creation <THROUGHLINE ONE>

Climate Changes Everything: A Horizontal World Made Vertical <THROUGHLINE TWO>

Destiny’s Child: How Demographics Determine Globalization’s Winners, Losers, and Future <THROUGHLINE THREE>

Superpower Brand Wars: The Global Middle Seeks Protection from the Future <THROUGHLINE FOUR>

Globalization’s Consolidation Is Hemispheric Integration: America’s Goal of Stable Multipolarity Preordained This Era <THROUGHLINE FIVE>

The West Is the Best: Our Hemisphere Is Advantageously Situated for What Comes Next <THROUGHLINE SIX>

The Americanist Manifesto: Summoning the Vision and Courage to Remap Our Hemisphere’s Indivisible Future <THROUGHLINE SEVEN>

AN AMERICAS-FIRST GRAND STRATEGY: CROWDSOURCING THE RIGHT STORY, CHOOSING THE RIGHT PATHS <CODA>

I could say that America is at a turning point, but that would disguise a darker truth—namely, that we are at a turning-back point. Too many of us choose to resist the future and escape the present by retreating into the past. This hardly makes us unique. Many economic powers facing decline reject reinvention, instead embracing the fantasy of recapturing lost greatness by scapegoating “evil” internal forces deemed responsible for this “treasonous” outcome. And if democracy is hollowed out by this viciousness? That just tees up the authoritarian reboot.

The politically inexpedient truth is this: America has spent the last seven decades systematically promoting a liberal international trade order whose cross-border flows of goods, services, technologies, investment, migrants, information, and entertainment have methodically integrated the world’s major economies, creating profound levels of interdependence among nations, peoples, and cultures—what we now call globalization (Throughline One). Our goal was simple: preventing world wars through increasingly inclusive economic advance. America was fantastically successful in this world-shaping grand strategy, globally creating more wealth and reducing more poverty across those seven decades than had occurred in the previous five centuries.

With the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, a new world order emerged with America as sole superpower, a situation that naturally invited Washington’s overreach on its unilateral policing of regional crises. Our nation wisely remedied that imbalance by encouraging the peaceful rise of other great powers—most notably China. In the meantime, Washington vigorously wielded its unmatched power, toppling nefarious dictators, disrupting transnational terror networks, and radically speeding up globalization’s advance. When the Great Recession hit in 2008, our citizenry correctly perceived that America’s success in encouraging the rise of numerous economic powers had significantly diminished our ability to steer global developments. At this point, China and other rising economies helped sustain globalization’s transformation into an increasingly digitalized phenomenon defined less by the flow of goods than by services and content, giving lie to simplistic notions of de-globalization.

Even in the post–Cold War era, America’s grand strategy remained phenomenally successful, enabling the emergence of a majority global middle class long thought impossible. Now, because the bulk of humanity spends a growing share of its income on things beyond the bare necessities, the world enters an age of superabundance matched by super-consumption. That unprecedented achievement has turbo-charged three global dynamics that, in their daunting combination, caused Americans to recoil from our glorious creation (globalization) and demonize it as the cause of all our problems.

There is no denying globalization’s role in spiking these global crises, but we must reject the hindsight that their emergence invalidates America’s strategy of encouraging globalization’s poverty-eradicating advance. We made the world an infinitely better place that now faces new challenges. Who can argue that humanity’s economic betterment should have been denied—despite these costs?

The first of these tectonic forces set into motion by skyrocketing global consumption is accelerating climate change (Throughline Two), which, like globalization, began reshaping the planet soon after America took it upon itself to steer the world’s development following two world wars. Climate change now remaps the planet, tragically rendering much of Middle Earth—my term for the lower latitudes extending 30 degrees north and south of the equator—systematically unable to sustain, without outside assistance, their exploding populations, national economies, and ultimately their political systems. Climate change is also creating enormous new areas of economic opportunity across the North. Accommodating this vast poleward transfer of natural wealth—to include all manner of species and peoples—will test humanity’s ingenuity and empathy like no global dynamic before it.

The second force is the global demographic transition (Throughline Three) stunningly accelerated by globalization’s rapid integration of Asia, home to over half of humanity. Our species will collectively age across this century in a manner totally at odds with both nature and human history: the old surpassing the young in nation after nation. That demographic transformation will factor heavily in the superpower struggles now unfolding. Youth-bulging powers tend to be warlike and unstable (recall America’s violent 1960s), while elderly societies retreat into nostalgia and social rigidity (see Japan and Italy today). Even nations achieving a large middle class succumb to virulent bursts of nationalism (China and India already). The good news? There are ways to avoid extreme aging, and America is supremely endowed with such capacity. We just need a bigger Union and a new map to that destination.

The third of these global forces arises in how the first two dynamics—climate change and demographic transformation—will collide across this century (Throughline Four). That collision will dramatically redefine Middle Earth’s economic needs and political priorities, and the superpowers (US, European Union [EU], China, India, Russia) that most effectively meet those needs and address those priorities will see their global influence radically expand. In responding to Middle Earth’s increasingly dire plight, these five powers will invariably compete in propagating new models of North-South security, economic, and political integration. Russia’s Vladimir Putin and China’s Xi Jinping have openly voiced such ambitions, imagining their own new maps. India’s minister of external affairs has declared his nation’s duty to serve as champion of the Global South on climate change and economic development. Washington, swept up in its political infighting, seems dimly aware of a competition already begun.

America’s economic future is on the line here: Much of the world’s consumer growth will be concentrated across Middle Earth, meaning the race to integrate North and South will simultaneously constitute a superpower brand war—an avowedly ideological competition to prove which economic model of trade and development best preserves and expands the global middle class amidst climate change’s destabilizing impact. Capturing the political allegiance of that ascendant middle class will determine which superpower’s definition of global stability reigns supreme in the decades ahead. If America wants to possess both power and influence in this remapped future, it cannot sit out this contest obsessively guarding its borders.

We have long framed superpower competition as which side (East or West) captures more of the other side’s players. In the future, we will define it as which Northern power most comprehensively integrates its respective South—ameliorating its climate-induced decay and preventing its virtual absorption by competitors. This new superpower competition will define our era, either seeding a second American Century or launching some other (Chinese? Indian?). No matter which superpowers prevail, regional and hemispheric integration will flourish (Throughline Five). This tightening of supply chains represents less a de-globalization than an optimization of material trade befitting the rise of multiple competing consumer blocs across the global economy. A generation ago, Asia manufactured goods for the rest of the world. Now, it manufactures largely for itself. On its own, this positive development has triggered a remapping of global value chains—an absolute good generating regional trade efficiencies. In this next iteration of globalization, those superpowers accumulating the most demand power will rule global consumer tastes in a way America once did—and now faces losing.

In this century, superpowers will prevail not according to the millions they field as lethal soldiers but the billions they attract as loyal subscribers. Size matters in this struggle to shape globalization’s future, which means America will be disadvantaged compared to far more populous China and India. These United States will be greatly incentivized to grow their ranks—as they have long done—by integrating hemispheric neighbors. By scaling its demand power, a once-again expanding American Union can constitute an economic center of gravity of equal or superior attractiveness to the global middle class whose brand loyalty we seek.

Rest assured, come midcentury, we will all be living in somebody’s world. I simply prefer our map over China’s for reasons I will make eminently clear.

To our great good fortune, America’s position as the dominant economic power of the Western Hemisphere clearly advantages us for the North-South integration to come (Throughline Six). Our true West enjoys several natural resource advantages over the far more crowded, diverse, and historically conflicted Eastern Hemisphere. The Americas also share culture and civilization worth defending on their own merits. By capitalizing on these advantages, America stands to benefit environmentally by managing climate change’s harsh equatorial impact, as well as economically by adding Latin America’s middle-class consumer power to that of North America. That larger union, however achieved, will then be able to extend its rule-setting power to significant portions of the Eastern Hemisphere, merging with regions not wholly lost to China or India’s economic orbits. For now, consider the entire board in play.

I understand why any call for hemispheric integration feels an inconceivable reach from where we stand domestically today, but our current bout of nativism and xenophobia highlights the powerful pull of this very path (Throughline Seven). In other words, what we now fear most is that which we sense is inevitable. Like comedy (tragedy plus distance), conceivability emerges with enough pain and time. With Central America’s environmental refugees already stressing our southern border, America is just beginning to feel Latin America’s pain on climate change.

I likewise understand the instinct to wish away the problem of climate refugees by insisting that technological solutions can spare us this path, but this book purposefully focuses on adaptation versus any such direct responses, which I stipulate will be made and will succeed to some extent—just not fast enough to forestall the global dynamics explored here.

Thankfully, we do not start from scratch. After all, America started out as a baker’s dozen of independent colonies. Today, hemispheric integration is likewise achievable through mechanisms and approaches already employed by both the EU in the political realm and China in the economic realm. Both carefully crafted integration schemes ultimately target security integration—the ability of superpowers to defend and optimally police their chosen spheres of influence. Meanwhile, America, lost to its intergenerational culture wars, satisfies itself with limp efforts to revitalize and extend military alliances focused on containing Chinese expansionism—a defensive and reactionary strategy more appropriate to retrograde Russia than the forward-leaning, world-shaping superpower we have long been.

Americans are modern globalization’s original networkers, wiring the world in our wake. By nature, we are a revolutionary force offering nations increased connectivity to all manner of economic opportunity and disruptive content. China and Russia, by comparison, offer control—namely, a model and means for national governments to surveil their growing middle-class ranks, restrict their access to disruptive content, and aggressively thwart their inconvenient tendency toward democracy.

This is where our national infighting becomes self-destructive: the world is watching how America navigates a future where our leadership is not a given, nor our ideals naturally preeminent. We witness Americans increasingly resenting—even as we increasingly resemble—a globalization originally made in our image but now no longer with our likeness. We ran this show for decades, but our success in creating this world cost us control over it—by design. Now, with climate change fueling the poleward movement of all life, globalization’s churning of races, species, and microbes lies beyond anyone’s control.

That intimidating reality transforms America’s global leadership while reaffirming its enduring source. Our nation has been—and always will be—a petri dish of globalization’s evolution. These United States remain the world’s source code for both integration (our immigrant nation’s fabled melting-pot dynamic) and disintegration (our institutional racism and chronic culture wars). We are globalization-in-miniature—its de facto proof of concept. America does not take its political cues from the likes of Hungary.

Americans do not endure history; we make it. This is our true superpower: reliably re-setting our internal rules in response to history’s punishing waves of change, and then spreading those new and better rules across the world. American grand strategy does not merely confront rivals but shapes a global environment that tames their—and our—worst impulses. We are the best thing to ever happen to our world.

Russia and China aggressively market their competing rulesets, exploiting vulnerable trade partners who distrust and dislike them. Yet both regimes, as internally brittle as they are, currently outpace America’s half-hearted attempts at global leadership. How is this so? It is because the stories we now tell of globalization do not envision a happy ending, much less a way ahead. No surprise there: when creators abandon their creation, monsters abound.

My task here is to propose that happy ending, one avowedly cast from an American perspective. Your task, as reader, is to maintain an open mind as to its feasibility and desirability. If, as our politicians love to proclaim, America’s best days lie ahead, then we citizens cannot merely await that future but must craft its story lines—both foreign and domestic. Given our truly revolutionary achievements, we must not allow our currently flat trajectory to determine the upper bounds of our ingenuity and ambition, both of which the world desperately needs now.

As such, this book is all about unearthing globalization’s throughlines and their constituent threads, operationalizing—through storytelling—that navigational knowledge across America’s political leadership, business community, and citizenry. Throughlines are those persistent national and global drivers that Americans will confront, balance, and trade off as we manage the national and global challenges laid out here. Think of them as history’s guardrails forcing us down a plausible range of pathways—certain inevitabilities that compel us to consider some version of the inconceivables we must in years ahead embrace. As for the connecting threads parsed within each throughline, consider them our protagonist’s inner dialogue about the fork-in-the-road decisions lying before us. Now, more than ever, the world needs America to stay in character—my overriding purpose in writing this book.

Let our storytelling begin, for therein we discover the contours of America’s new map.

Thursday, March 9, 2023 at 8:10AM

Thursday, March 9, 2023 at 8:10AM  Find the LinkedIn post announcing my joining Throughline here.

Find the LinkedIn post announcing my joining Throughline here.

I could not be more grateful and excited for this opportunity.

Thursday, October 20, 2022 at 11:55AM

Thursday, October 20, 2022 at 11:55AM Just settled on the title with publisher BenBella.

It will come out in Sept of 2023.

Will be about 55,000 words with 50 or so illustrations (hand-drawn) and about two dozen data diagrams.

Monday, January 17, 2022 at 3:11PM

Monday, January 17, 2022 at 3:11PM Collaborating with a design/strategy firm out of DC.

Almost done with the book proposal now.

Looking at about 80,000 words with custom illustrations (think AlphaChimp-style) and sophisticated data diagrams.

Tentative title is "America's New Map," but initial titles rarely survive the publication process.

As for why it took my so long to write another book? I simply needed down time and think time to accumulate enough material for one. I was never good at commenting on current events and found that to be a mind-drain, especially during the Trump years (What point to be the 1,342nd tweet to point out something as stupid or disastrous?).

But I am VERY excited to be moving again now.

Tuesday, November 2, 2021 at 11:26AM

Tuesday, November 2, 2021 at 11:26AM

I’m a professional writer with over 500 publications spread over four decades, and yet, in this digital age, I can’t get my hands on electronic copies of probably 90 percent of them. All of them were originally created in digital form, but many found publication solely in print while others now live behind firewalls. I tried my darnedest to keep electronic copies of them all, but just try maintaining that kluged database over a dozen or so computers I’ve had over the years, the conflicting operating systems, the various websites, the hard drives that failed, and the file versions or programs that are no longer supported or even exist. Yes, I’m plenty grateful the cloud came along in my middle years, but even that is frankly nothing more than another file cabinet that’s largely unsearchable – at least in the ways I’d like to be able to manipulate it.

In many ways, my online blog has served as my primary professional memory. It’s where I’ve recorded just about everything I’ve ever written, and it’s crudely searchable. But it’s at best a pointer system, as in, look over here for that article you’re trying to remember! I can’t easily compile, for example, the hundreds or even thousands of times I’ve written something about China, the internet, the Defense Department, or really anything. Frankly, I am often reduced to Googling myself to find that one passage that I want to review and maybe update/repurpose in something new that I’m working on.

Frustrating, right?

Then realize that the vast majority of my writings were never published. They were filed away in all manner of proprietary systems. I’m talking about thousands of memos and reports and notes – often just to myself. Toss in the 15,000 blog posts and probably the same number of relevant and useful emails (heck, probably several times more), and you come to realize that, for someone in the writing business, I’ve produced a vast quantity of material – truly a uniquely useful knowledge base, to me at least – that I don’t really have that much access to, much less the ability to leverage and build upon.

Like a lot of writers, I want what I’m working on right now to be the best thing I’ve ever written, so I’m naturally wary of digging into my past too much – and yet, living and working in a world of Big Data has sensitized me to the notion that all content is pretty much an extension and synthesis of what’s gone before. This is my professional body of knowledge floating out there in the ether and I should be able to mine it – at will!

So, imagine that capability.

Imagine a cloud database that you have diligently fed over the course of your professional life: every email, every document, every article, every everything. You just always CC’d to it – within the law and your contractual obligations, mind you – a copy of everything you ever penned. It is your database, accessible to only you (or those you might wish to collaborate with) and always there for you to tap.

Say I need to write something on Iran and I know I’ve mentioned or described that state maybe thousands of times over the decades. I go to my personal cloud-situated knowledge base and type in the term on my content-review interface, along with a contextualizing pair of other terms to narrow down my search (e.g., nuclear weapons, terrorism). Seconds later I’m looking at scores of hits spread out over the past X years – stuff I forgot long ago, or no longer adhere to, or still adhere to but need to update.

So now I’m cherry picking the best bits by simply clicking and dragging pieces of text – the vast majority of which has already been edited to a hard polish – and within minutes I’ve compiled a career’s worth of professional knowledge (along with the citations) that jump-starts my current writing project on Iran.

What would I give for that convenience, speed, reach, and recollection? Like most professional writers, I’m pretty good at synthesizing, repurposing, updating, and extending existing content – except now I’m doing it at ludicrous speed, mining material that I inherently know and trust. So yeah, that would be worth something to me.

Well, that’s what my new company, Riverscape Software, is building and testing right now: a cloud-based document generator with dedicated document repository. Those are two of several modules in a SaaS designed to super-empower small businesses operating in the increasingly sped-up world of Federal contracting, where government-wide Indefinite Duration, Indefinite Quantity (IDIQ) contract vehicles have transformed the public tendering landscape into a never-ending torrent of Task Order Requests (TORs) to which all firms – big and small – must reply at high speed with highly complex proposal volumes.

Riverscape Software will launch our SaaS, dubbed InfoSquirrelTM, in early 2022. It’s currently being field tested by a top-20 research university and one of its extension services as they collectively look to upgrade their capacity to respond to government solicitations – particularly grant proposals.

Meanwhile, we wanted to start an informal dialogue with what we believe to be a rather large market for this SaaS and/or its individual modules – like the document generator described in this post. As Riverscape Software’s Director of Strategic Communications, I just wanted to start this conversation with a writer’s viewpoint on what is – to me at least – the most exciting part of InfoSquirrelTM – namely, its ability to super-empower authors who, like me, typically operate under tight deadlines to produce large amounts of professionally complex content.

This is admittedly a bit of a product tease, but I wanted to start small. Other posts will follow in the weeks ahead. Please reach out to me (thomas.barnett@riverscapesoftware.com) with any reactions, thoughts, or interest. We know we’re onto something here, because we’ve spent the last year using InfoSquirrelTM to increase our proposal submissions 8-fold(!) over the past two years. But to be honest, we are just scratching the surface of what the entire InfoSquirrelTM module suite will ultimately be used for, so we’re looking for fellow-travelers on this fascinating journey of discovery.

Thursday, September 2, 2021 at 8:18PM

Thursday, September 2, 2021 at 8:18PM

Delivered 31 July 2021 at Immaculate Conception Parish, Boscobel Wisconsin.

On behalf of my family, I want to thank you all for joining us here to celebrate Colleen Ann Clifford Barnett. This space is - without a doubt - the spiritual center of gravity for our family, and you, her family and friends, are all she would have asked for today.

Our mother was born in Green Bay and grew up as Packer royalty thanks to her father’s seminal role in that franchise. The Packers were everything to Mom and, on that basis, remain everything to her family.

An example: my wife Vonne and I switched faiths for a time, during which we baptized our second child Kevin as Episcopalian. Mom attended but wept openly during the entire ceremony. On the way out she fiercely hugged me and declared, “It could have been worse, Thomas."

"How?" I said.

She replied, "You could have become a Bears fan.”

Colleen Clifford met and fell in love with John Barnett, her husband of more than 50 years, at the University of Wisconsin law school. Upon their marriage, she left law school – hold that thought – and moved with John to Boscobel.

Colleen bore John 9 babies in 15 years – a testament to her love of children, physical endurance, and, as she liked to brag over the years, her profoundly loving relationship with our Father.

Mom was a fiercely protective parent, and her feats of strength were legend within our family. Once, during a hot summer mass in this church, we were sitting in the last row to accommodate Mom’s weakened state – as she had just been released from the hospital following surgery. Our sister Maggie, feeling dizzy from the heat, got up to go to the bathroom. On her way, she bumped into the holy water tank, alerting Mom, who immediately vaulted over the pew and caught Maggie before she hit the ground!

As Colleen’s last child entered grade school here, she joined Grant County’s social services department, where she helped establish many important programs that persist to this day.

Retiring at 62, our mother was re-admitted to the UW law school, becoming a genuine celebrity among her classmates. There was a longtime UW law professor who – as legend had it - had never been bested by any student in a mock cross-examination – until Colleen.

Now imagine being 19 years old and entering our living room at midnight with … something … on your breath – only to see Mom squinting at you from her recliner. Like that professor, you never really had a chance.

After law school, Colleen spent a decade working as a lawyer, divorce mediator, and instructor at UW Richland Center.

If that wasn’t enough, Mom began her writing career in her seventies, methodically authoring the definitive three-volume encyclopedia of leading women characters in mystery fiction – triggering her celebrity within that literary circle, to include nominations for industry awards and presentations at national conventions.

Mom had an incredible drive and boundless curiosity – all of which she imparted to her children and this community by serving on boards, commissions, and councils.

Mom was brilliant at organizing things and people, setting goals, and motivating action. "Make your life an adventure," she would tell us. "Never regret your failures, for they are the making of you."

True to form, Mom constantly experimented as a parent, making us in the process

An antique cow bell called us home for dinner, on time and salivating like Pavlov's dogs.

Reading lights clipped to our beds made us all avid readers.

Our childhood was a never-ending series of challenges, competitions, and tests. I was introduced to public speaking well before kindergarten, thanks to Mom’s question of the day at our dinner table each night. The Barnett kids had to speech for their supper.

Tie your shoes for the first time? $5 from Mom.

Ride your bike - no training wheels - around the block without stopping? Another $5.

Let's be honest here: a lot of Mom's schemes were thinly devised efforts to get us kids out of the house. Her favorite way to dismiss us was to bark, "Now get out of here!"

When our brothers - first Andrew, then Jim, ultimately Ted - were diagnosed with dyslexia, thanks to Mom's persistence at a time before learning disabilities were even recognized, she had numerous experimental devices built to exercise their hand-eye coordination. Mom made those drills seem so cool that neighbor kids would line up to do them. To this day I brag about almost being dyslexic – I was this close to getting that badge!

Mary Poppins had nothing on Mom.

After Dad died, Mom left Boscobel to live with our sister Maggie in St Paul. There, she became in-house grandma to Maggie’s daughter Ally.

That transition softened up Mom quite a bit, but she was still Mom. Every year I’d get this gloriously worded birthday card: you are the best son in the world, and so on. Then I’d glance down and see, in her handwriting: “Don’t let it go to your head! …. Love, Mom.”

We'd ask Mom, "Who's your favorite child?" She'd reply, "The one who needs me most right now" - a promise she always kept.

It has been an incredible privilege to have Colleen in our lives all those 95 years – a blessing beyond calculation.

And so, I ask for your continued prayers – not for Mom and her soul; trust me, God skipped that cross – but for whatever you hold most dear and for our world at large. Nobody believed more in prayer than Colleen.

Every child grows up thinking that the world is just like their family.

All I can say, in conclusion, about Colleen Ann Clifford Barnett, is that she left her 7 surviving children – and by extension her two dozen grand and great-grandchildren – a wondrous, beautiful, adventure-filled world where parents live for children, marriage is for life, and love is forever.

All this ... because two people fell in love.

Mom, thanks for everything.

Dad, she's all yours.

Friday, August 27, 2021 at 1:07PM

Friday, August 27, 2021 at 1:07PM Kagan has consistently been the best analyst on the Global War on Terror.

Find his lengthy WAPO op-ed here: https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2021/08/26/robert-kagan-afghanistan-americans-forget

Nothing for me to add, except to highlight finall three grafs:

In fact, the “war on terror” has been successful — astoundingly so. If you had told anyone after 9/11 that there would not be another major attack on the U.S. homeland for 20 years, few would have believed it possible. The prevailing wisdom at the time was that not only would there be other attacks, but they would be more severe. In 2004, Harvard’s premier foreign policy expert, Graham Allison, predicted that it was “more likely than not” that terrorists would explode a nuclear weapon in the United States in the coming decade. What former Obama and current Biden officials Rob Malley and Jon Finer observed three years ago remains true today: “No group or individual has been able to repeat anything close to the devastating scale of the 9/11 attacks in the United States or against U.S. citizens abroad, owing to the remarkable efforts of U.S. authorities, who have disrupted myriad active plots and demolished many terrorist cells and organizations.”

That this fact is rarely noted as Americans argue about Afghanistan is remarkable. Does anyone think these efforts would have been as successful if after 9/11 the United States had left the Taliban and al-Qaeda in place for all these years? And it is interesting that so many Americans now believe the price has been too high. As often happens, the fact that the United States hasn’t been hit again tends to reinforce the idea that there never was a serious threat to begin with, certainly not serious enough to warrant paying such a price. But this is again the difference between living history forward and judging history backward. If someone had told Americans after 9/11 that they could go two decades without another successful attack but that it would cost 4,000 American lives and $1 trillion, as well as tens of thousands of Afghan lives, would they have rejected it as too high? Likely not.

When Americans went to war in 2001, most believed that the dangers of inaction had become too great, that threats of both international terrorism and weapons of mass destruction were growing, and that serious efforts had to be made to address them. Today, many Americans increasingly believe that those earlier perceptions were mistaken or perhaps even manufactured. With America’s departure from Afghanistan, we may begin to learn who was more right.

Sunday, August 22, 2021 at 12:03PM

Sunday, August 22, 2021 at 12:03PM Entitled "Biden Pulled Troops Out of Afghanistan. He Didn't End the 'Forever War': Presidents since George W. Bush have fashioned a military strategy that knows no borders - and isn't dependent on boots on the ground"

Author is Samuel Moyn, Yale prof. Found here.

Years ago in The Pentagon's New Map I wrote that the "boys are never coming home."

And they still aren't.

Yes, their numbers will be much smaller because we'll fight very differently than in the past. We started the Global War on Terror with a Leviathan force but we're continuing it - forever - with the SysAdmin force that does not wage war on states but on individuals - the reality of US "war" going all the way to Noriega and Panama in the late 1980s.

That reality remains no matter how much we fantasize about high-tech wars with China - a total chimera for which we will still prepare (and waste untold sums - but not all) even as we continue to overwhelmingly operate with the SysAdmin force that does not seek to "win" so much as manage the world as we actually encounter it.

The key bits:

The hue and cry surrounding the collapse of the Afghan government and the fall of Kabul — the debate about who is to blame and whether President Biden erred in ending military support (and in how he did so) — should not distract from two important truths. The Afghan war, at least the one in which American troops on the ground were central to the outcome, was over long ago. And America’s ever-expanding global war on terrorism is continuing, in principle and practice ...

Biden’s withdrawal of those final troops is clearly significant. But setting aside today’s self-regarding American conversation — across mainstream media, Twitter and the like — about where and when “we” went wrong in our attempt to free Afghanistan, we should recognize that their departure in no way extricates America from its ongoing, metastasizing war on terrorism. When Biden declared in April, “It is time to end the forever war,” he was referring to a withdrawal of troops from Afghanistan. But the phrase “forever war” is better used to describe the expansive American commitment to deploy force across the globe in the name of fighting terrorism, a commitment that is by no means ending. In his extraordinary speech defending his actions Monday, Biden made this very clear, distinguishing the “counterterrorism” that the United States reserves the right to conduct from the “counterinsurgency or nation-building” that it is giving up.

The last bit oversells:

Beyond the genuine costs and humanitarian consequences of the fall of Kabul, which are not to be underestimated, the continuing reality is even scarier: The United States has over the past two decades created an all-embracing and endless war that knows few geographic bounds. Current events are likely to make that conflict even more permanent.

It's not "scarier" by any means. I think the author was just reaching for a punchy ending to his op-ed. Fighting a global, borderless war with the Leviathan force would be scary - and pointless. Doing the same with elements of the SysAdmin force, which pulls in technology and special forces and police and all sorts of other assets from allies around the world ... that is simply the reality born of 9/11, when we finally chose to embrace that global struggle years after it had embraced us.

Thursday, April 1, 2021 at 10:42AM

Thursday, April 1, 2021 at 10:42AM  Photo credit: Nadya Chikurova& Pablo FernandezEntitled, "Biden Must Clean Up the Trump Pardons," the gist is that the Constitution prohibts presidential pardons during an impeachment process because those acts are easily construed as buying-off jurors.

Photo credit: Nadya Chikurova& Pablo FernandezEntitled, "Biden Must Clean Up the Trump Pardons," the gist is that the Constitution prohibts presidential pardons during an impeachment process because those acts are easily construed as buying-off jurors.

With the battle building over the filibuster, there’s another area that cries out for Senate reform: the impeachment process that led to the recent acquittal of Donald Trump.

No senator should be allowed to serve as a “juror” if they’ve benefited from a pardon issued by an impeached president. In this case 12 senators, including 10 Republicans, had sponsored Trump’s last round of pardons, creating the appearance of a conflict of interest and lack of impartiality.

Find the entire piece at Who.What.Why.

Saturday, August 1, 2020 at 1:07PM

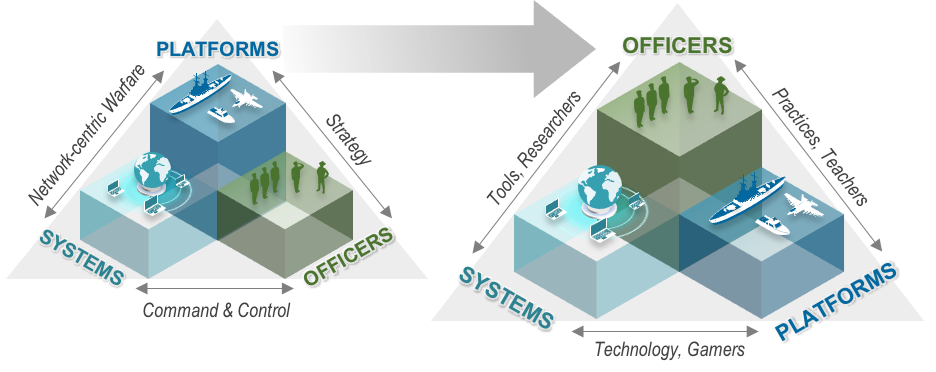

Saturday, August 1, 2020 at 1:07PM

On May 1st, the nation’s war colleges received a brutal – if pre-emptive – failing grade from the Joint Chiefs, who declared that Joint Professional Military Education schools are not producing military commanders “who can achieve intellectual overmatch against adversaries.” Because China increasingly matches our “mass” and “best technology,” the Joint Chiefs argue that America will prevail in future conflicts primarily by having more capable officers. As for those “emerging requirements” that “have not been the focus of our current leadership development enterprise” (e.g., integrating national instruments, critical thinking, creative approaches to joint warfighting, understanding disruptive technologies), please raise your hand when you hear something new.

Brutal and timely ...

Wednesday, July 29, 2020 at 6:06PM

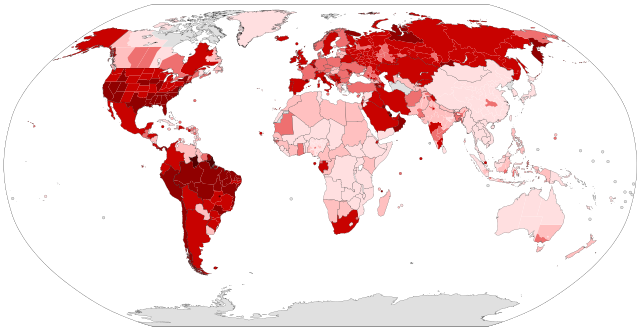

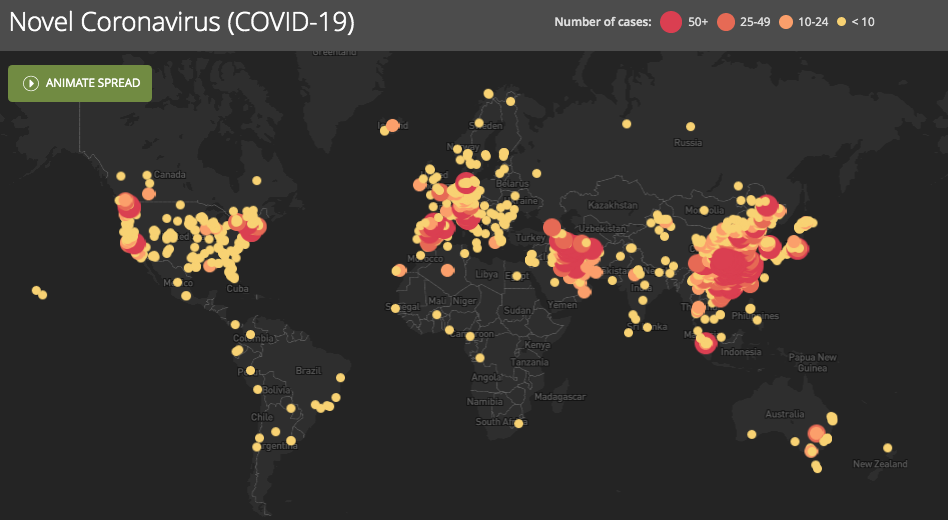

Wednesday, July 29, 2020 at 6:06PM  COVID-19 Outbreak World Map per Capita (Wikipedia)Some simple back-of-the-envelope calculations that came to me while on a long bike ride today ...

COVID-19 Outbreak World Map per Capita (Wikipedia)Some simple back-of-the-envelope calculations that came to me while on a long bike ride today ...

Question: which G20 members have suffered a smaller/larger percentage share of global COVID deaths relative to their share of global population?

G20 encompasses 63% of world population, but it's the more economically advanced share, so we should expect the G20 as a whole to suffer less than 63% of global COVID deaths.

In truth, for now, it seems that the G20 account for roughly 4/5th of global deaths, or 80%. So, as a whole, the G20 underperforms. With all that wealth, you'd expect a share far below 63%. Of course, as the pandemic hits the world's poorer areas over time, the G20's share will drop. Still, not a good performance.

Let's look inside the G20 to see who's outperforming their global share of world population and who is underperforming. In the latter case, that country's percentage share of COVID deaths would exceed its percentage share of global population.

NOTE: all the numbers here come from Wikipedia sites, which draw upon reputable sources. Again, these are back-of-the-envelope calculations in search of a reasonably fair assessment of government performance.

First, a list of the G20 members outperforming on COVID (defined as percentage share of global population being higher than percentage share of global COVID deaths):

Now the list of G20 members basically performing as expected, meaning the percentage share of global population is roughly matched by the percentage share of COVID deaths:

So, 13 of the G20 performing as expected or better - stipulating that some nations are under-reporting but unlikely to be doing so in such a way as to change their performance from positive/average to bad in any profound sense.

Now for the underperformers:

Now the underperformers ranked by severity (defined as the biggest gap in percentage shares):

If you translate that point gap into excess or preventable deaths, then it is expressed as follows:

If we fold UK, Italy, and France into the EU, then we're talking 383,000 lives in total.

We can debate the right adjective here: unnecessary, wrong, sacrificed, lost, etc.

I prefer to think of it as simply a rough estimate of what poor government performance - largely expressed in bad political leadership - actually costs in human lives during a disaster such as this.

Thursday, May 14, 2020 at 1:03PM

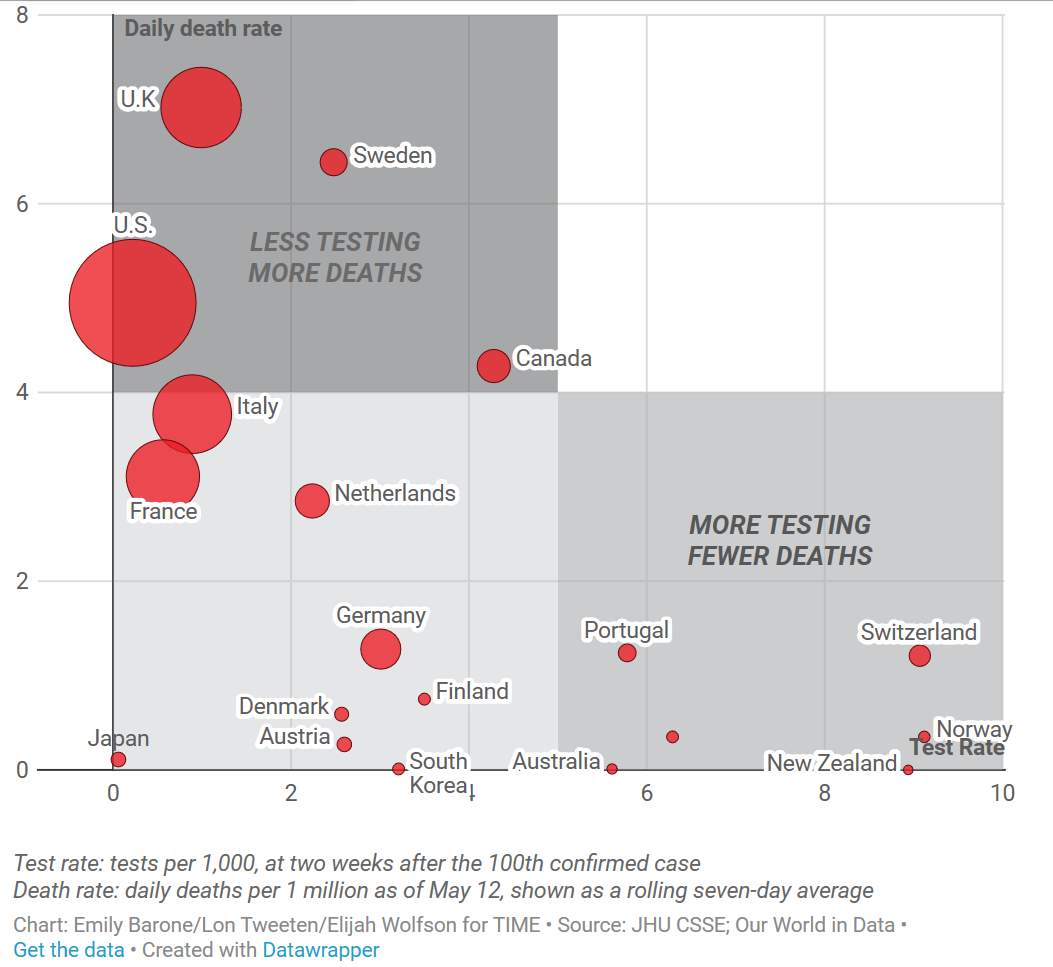

Thursday, May 14, 2020 at 1:03PM Seems pretty obvious that, to do well, you craft and execute an aggressive national testing strategy replete with large-scale tracking corps.

The United States has done neither, with the Federal Government taking a pass and declaring it all up to the presently overwhelmed (in many instances) states.

So we are losing the COVID-19 "competition," as this chart makes clear.

There is no good reason for this failure, and it seems poised to ruin any large-scale re-opening of the economy, which is very sad for all involved.

Our national economy is experiencing an extinction-level-event in terms of households, jobs, skills, business models, and even entire industries. The "mammals" will get by, but loads of "dinosaurs" will disappear.

It did not have to be this way. We needed a strong and competent federal government for this crisis, and we did not get one.

Wednesday, May 6, 2020 at 10:58AM

Wednesday, May 6, 2020 at 10:58AM

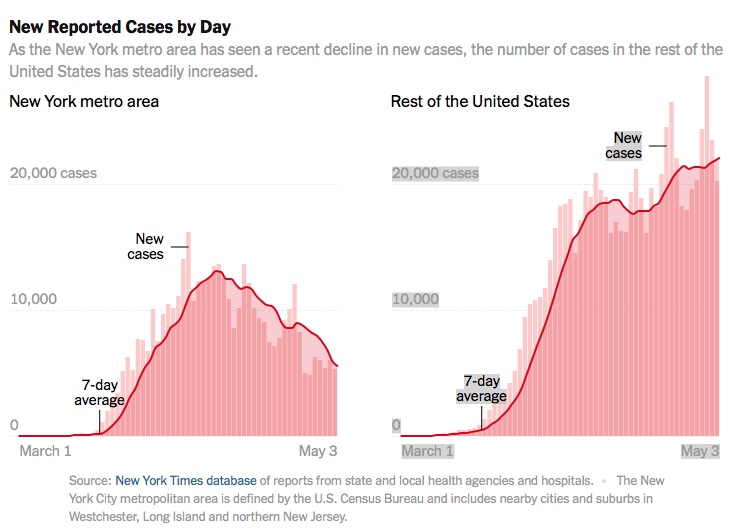

From NYT coverage.

Everything you need to know about where things stand right now.

Fair to compare NYC with entire rest of nation? When the former has accounted for roughly half the deaths so far ... yeah, sad to say.

Up to now, COVID19 has been rougher on Blue urban bastions, leaving the rural Red skeptical and prone to "magical thinking," as the story here implies.

We'll see how that changes as this pandemic grows a whole lot less fake news-y for a major swath of our nation.

Thursday, April 16, 2020 at 7:04PM

Thursday, April 16, 2020 at 7:04PM  Referencing the current Commandant's recent interview with War on the Rocks, summed up nicely here with General David H. Berger stating:

Referencing the current Commandant's recent interview with War on the Rocks, summed up nicely here with General David H. Berger stating:

Our approach to that critique of, “You’re building a very tailored force for the high end, not applicable in the most probably anticipated or most probable kind of scenario”— here’s how I would characterize that. We’re building a force that, in terms of capability, is matched up against a high-end capability. The premise is that if you do that, if you build that kind of a force, then you can use that force anywhere in the world, in any scenario; you can adapt it. But the inverse is not true. If you build a low-end force, or a medium (however you want to characterize it), if you build that capability of a force, you cannot ramp up against a higher end adversary.

Earlier in the interview Berger states that the USMC needed a redesign to correct the overt force "heaviness" it had embraced due to its lengthy ashore ops in Afghanistan and Iraq. Why did it need to change over those years? Because its previous focus on high-end warfare had left it massively unprepared, woefully undertrained, and fatally ill-equipped to fight those smaller wars that had previously been dismissed as "lesser includeds" (the logic being, if you can go big war, you can go small war as a natural subset). It wasn't true back then and it won't be true with this planned redesign.

Simply put, the choice to go big is the choice to neglect and avoid the so-called lesser-includeds.

But Berger's words perfectly sum up how the Marines' clock has been reset on the Big One: build the big force and you can use it small, but you can't go the other way around.

How the general can argue that, when it was so clearly proven in Iraq and Afghanistan to be untrue, reflects the wider strategic realities truly driving this change:

Notice how the Commandant speaks of "great power competition" but not great-power war per se. That's the second great flaw of this argument: our competition with China ultimately ends up being in the small wars/grey zones/soft power realms -- not in the much-dreamt-of, Michael Bay Transformers-style, high-end war-over-the-rocks-of-the-South-China-Sea scenario. Same is proving true with Russia on Ukraine, Syria, etc.

With this redesign, the Marines retreat back into the bosom of the Navy, which is historically where they embed themselves during downtimes like this.

I get the instinct. I just wish they'd come up with a new rationale rather than retreading the past. Updating the 1980s Maritime Strategy for the PRC strikes me as anything but innovation, as the Marines won't be any more meaningful to that scenario than they would have been in that previously imagined WWIII.

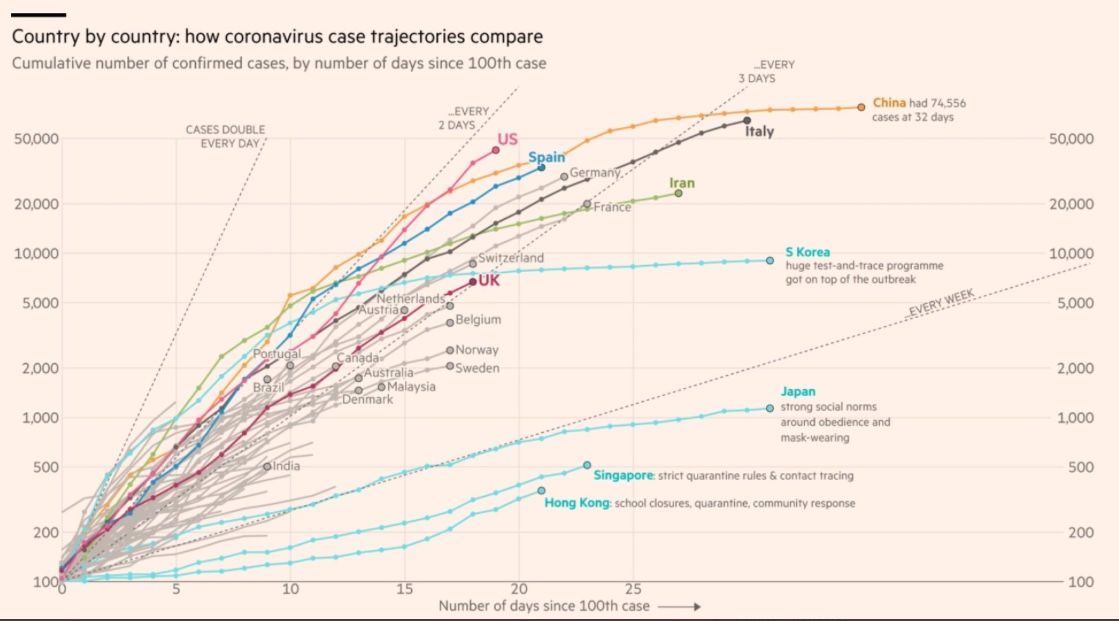

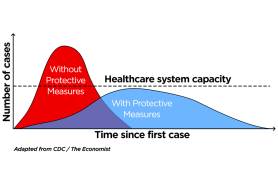

Tuesday, March 24, 2020 at 12:36PM

Tuesday, March 24, 2020 at 12:36PM

Obtained, via WAPO "The Daily 202," from here.

The "cone of plausibility" is a graphical representation of a range of plausible downstream scenarios expanding outward from today's current reality. See here for a description.

What is presented here is the exhibited reality of numerous states, indicating that most, once trapped in the coronavirus dynamic, suffer a post-first-100-cases trajectory of rough doubling of cases between every 2-3 days. That's the cone.

Those who did better? For now, they are well-run Asian democracies (Japan and ROK), where collectivism trumps individualism (at least still when in crisis), so a mixture of social self-discipline, strong governments with extensive power and reach, and a high level of trust between leaders and led.

HK and Singapore appear to fall into that category, but I never put too much stock in city-states as exemplars. The scale is just too far off. China underperforms largely because government was looking out for itself for far too long in beginning, recovering only through fairly harsh measures - all very Chinese.

The West seems clearly clustered in that 2-3-day-doubling range, with probably speed-of-response being the key differentiator. We're on the high end in US because Red America blew it off until very recently, following the lead of POTUS and Fox News. With that dynamic hopefully muted for a while as vast majority of Americans now "come to Jesus" in taking this seriously, the big question looming is, How long can we continue doing what's needed, given the economic cost?

Already the speculation rises that POTUS will feel great personal financial pressures over his suffering properties (estimated to be losing 1/2M$ per day), and, while that's true, it's also indicative of the genuine economic pain, so maybe not the worst inpulse. Still, those external economic pressures would swamp any White House, so perhaps it would have been safer to have someone in charge right now with more financial "distance" from that dynamic (i.e., a traditional president). So now we watch Kudlow-vs-Fauci, with POTUS making comparisons to auto accident deaths, etc.

That's a natural tension in any crisis: When do we get to declare it's over? Americans are not a patient lot. And yet, the stakes here couldn't be higher. Right now the percent of Americans who've lost someone is tiny, but that will expand dramatically over the next month, making all this EXTREMELY personal to those affected. Loved ones die all the time from forces we cannot tame, but, as this chart shows, we CAN tame this dynamic, given the right balance between economic and human cost. Done well, maybe 2020 feels like a "double-cancer" or "double-heart disease" year (i.e., COVID-19 kills about 600,000), but done poorly - and given all the "war" talk, maybe a 60% infection rate, coupled with a 1% kill rate (both entirely plausible estimates), leaves 2 million Americans dead. That would be a slightly higher social cost than WWII was (or 2m of 330m as just 1/2 of 1% of Americans dying from COVID-19 versus 400k of 131m dying in WWII - or roughly 1/3 of 1%).

The experential data seems very clear on this: Even with a solid effort, the average country is looking at a peak-and-decline dynamic arriving in the range of 8-10 weeks after crisis onset. That is mid-to-late May for the U.S. We are getty antsy now, half-way through Week 2, so it's hard to imagine most citizens exhibiting the necessary self-discipline for another 6-8 weeks, even as the experience of other countries makes clear that is what is required if you want a semi-normal summer (hopefully) followed by a renewed battle in the fall, but one fought on far better terms.

Done right, POTUS pulls out a huge policy/leadership win even as the economic costs pile up and possibly ruin his re-election bid. George H.W. Bush did similarly with Desert Storm and the early 90s economic slowdown, but he took his fate like the real leader he was. I am far less hopeful in this current political climate.

Point of this chart SHOULD be: we know what we have to do, the only question is whether we value lives more than money.

I know, right? How very Bernie of a moment, but also a glimpse of our collective future. We hurtle toward Kurzweil's Singularity, reflective of our collective trajectory into the Age of Biology. Access to medical care/tech is already becoming THE human rights issue of this century, and experiences like this only accelerate those dynamics. By way of comparison, America's inevitable transformation into non-white majority status seems positively retrograde in terms of ideological stakes, even as it so clearly captures the political attention of so many citizens right now.

Per the adage about not wasting any crisis, we can hope that this pandemic alters our thinking here in America, reacquainting us with the emerging reality that this is the nature of crises in today's world (system perturbations, not fantasies of returning to strategic warfare with other great powers - much less the "grave danger" of invading immigrant hordes) and redirecting us off this racially-based identity politics and back onto issues of human rights concerning fair access to emerging health technologies and the care options they offer. With the rich and famous being treated so well (Your COVID test is in, Mr. Hanks/Mr. Gobert/Senator Paul!) while front-line healthcare workers jerry-rig protective gear, this crisis presents immense potential for another populist explosion in the upcoming election - likely to be our 8th "change election" in a row!

Here's hoping we come closer to the mark on this one.

Monday, March 16, 2020 at 11:45AM

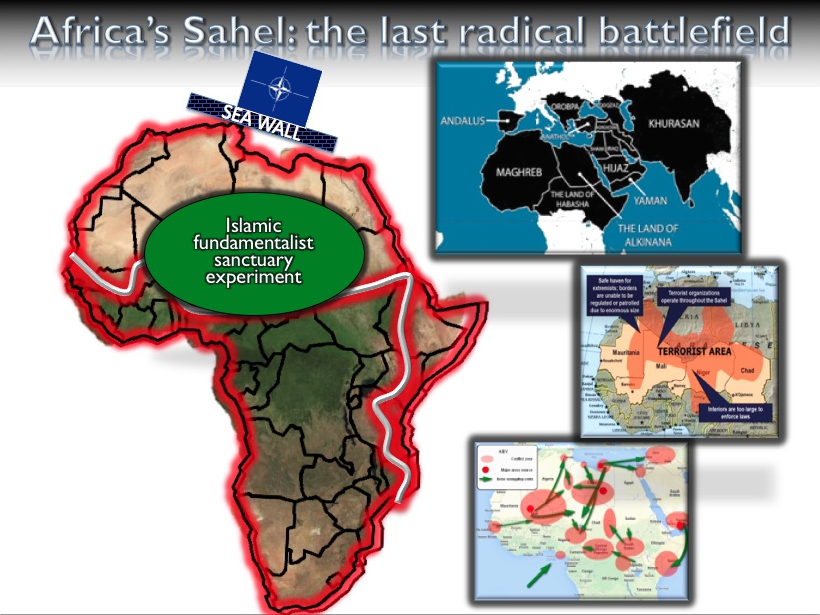

Monday, March 16, 2020 at 11:45AM  When I wrote my trilogy of books (Pentagon's New Map [2004], Blueprint for Action [2005], Great Powers [2009]), my primary purpose was to explore and explain what I thought was the new nature of crisis and conflict in the world.

When I wrote my trilogy of books (Pentagon's New Map [2004], Blueprint for Action [2005], Great Powers [2009]), my primary purpose was to explore and explain what I thought was the new nature of crisis and conflict in the world.

In the first instance, it is about globalization's rapid and penetrating embrace of lesser connected countries, or what I dubbed the Gap. By and large that is a great thing (reduction of global poverty, creation of first-in-history truly global middle class), but it's very disruptive of culture and tradition and power structures, and conflict (largely in the form of state and non-state resistance to all this rising and intrusive connectivity) ensues. That's why I called it the Pentagon's new map, my argument being, this is the nature of crisis and conflict.

The terror strikes of 9/11 represented that sort of new crisis: actors targeting symbols of connectivity (trade, security) and hoping to trigger a self-isolating effect (West leaves the Middle East). West, instead, came in force, triggering all sorts of refugee flows, revolutions, crackdowns, civil wars, etc. West got tired and now it's mostly the East working this problem, but the connectivity continues and grows - both good and bad.

As my previous post indicated, Y2K was, for me and many others, a scheduled practice-like glimpse into these dynamics of system perturbation as the defining form of international crisis (vertical shocks followed by long horizontal waves of impact).

Since 9/11, we've had the Great Recession and a variety of lesser pandemics. Now we're finally confronting the long-anticipated killer pandemic that is coronavirus - the first great replay of a Spanish Flu-like transmission under the conditions of modern globalization.

How are we handling it? Actually, pretty much like expected.

Authoritarian countries seek to hide or minimize the situation, while democracies are slow to act despite mounting evidence. This is to be expected. Vertical power systems like China know how to handle horizontally spreading crises like this through traditional means of centralized control. Once the initial vertical shock passes (Wuhan for China), vertical systems tend not to fear horizontal dynamics. They are built to suppress such dynamics. Vertical systems really fear the out-of-the-blue stuff at the beginning because it triggers that popular emperor-has-no-clothes realization that all dictators fear so intently.

Instead, it's the horizontal political systems (like US and democracies in general) that tend to struggle more with the follow-on horizontal scenarios like this. We see the vertical shock of Wuhan in the distance and we blow it off (too far away, nothing to do with us). Then we start noticing the horizontally travelling shock waves approach through the world's many networks. But, given our system and culture, we fear the imposition of vertical controls ("evil Washington," "black helicopters," "take my guns" and other fantasies) that oftentimes work best right off the start, and so - over time - we suffer being the land of a 1000 different responses. Who's in charge? Hard to say. News comes in from all angles (POTUS, CDC, Congress, governors, mayors, school districts, etc.). The broken-clock preppers are right again! And the rest of us fight the inner panic urge.

While that decentralized approach, at first, seems to makes the problem worse (and it can alright), over time, our horizontally-defined strengths emerge. Our horizontally-structured system is free to experiment across the board, and our free press (even under conditions of political polarization) are adept at discovering, critiquing, and spreading best practices as they emerge (God bless them, one and all). In the end, our horizontal political structures will tighten up some (centralize), but not wildly so, and they tend to re-relax over time as the crisis fades in memory and legal remedies ensue.

But lessons will be learned, and we will structure aspects of our polity, economy, networks, etc., to account for what we've learned. And yes, it will make us better next time.

The larger lesson that remains is the same one we've been learning for two-to-three decades now, or since the end of the Cold War freed our minds to look at our connected/connecting world without the overlay of the superpower conflict/great-power war paradigm: our modern world is defined by connectivity, which grows over time and sets the parameters of all meaningful crises and how we respond to, and grow from, them.

Yes, we may think we can unilaterally withdraw from that world - however selectively or broadly, but that's a myth.

Yes, we may think we can renegotiate all the terms of our connectivity with the outside world, and, while we can certaintly adjust, that's a multi-sided game now with all sorts of great powers trying the same trick at the same time, so rule-set clashes proliferate. These clashes are far from traditional conflict, but they do represent those powers realizing that, now that globalization is here, that is the best way to fight for what you want - or believe in.

Since 2016 America has sought to withdraw from the world, and it hasn't gone all that well. Our ability to set agendas, dampen great power tensions, or steer developments has been hugely diminished. So has the global appeal of our rule-sets, which we spent the previous seven decades advocating for, and spreading, around the planet. We are a much smaller power in the world right now, and we're increasingly nervous about that, because the world hasn't grown any simpler as a result.

The coronavirus crisis exposes the folly of our recent approach (The Wall being our most hilariously sad example), more saliently than the still-dismissable (in too many minds) slow-mo climate change crisis (which certainly drives the uptick in zoonosis transmission events [animals-to-human disease vectors] by pushing humanity and wildlife together in more disruptive synergies).

And so corona does us this favor: it reminds us of how far we've come in this globalization and how going-your-own-way is a fear-threat reaction beneath our standing as a long-time global leader and - indeed - the primary architect of the world we still find ourselves in.

And so we learn again about the nature of our globalized world, the threats it poses and the crises it generates, and - hopefully - we once again reconsider our recent slide toward fantasizing about the return of conventional/strategic great-power war as a possibility (or, more insanely, as an inevitability) and we re-embrace what we re-learn everytime we endure one of these vertical-shocks-triggering-scary-horizontal-waves ...

Namely, that we are all in this together, and increasingly defined by our global connectivity.

We can try to shape that hardening reality for the better, or we can stick our fingers in our ears and scream nonsense in an effort to block this reality out. In our worst fears, we can always retreat to nostalgia, demanding that the homogenous world-of-our-youth magically return. But frankly, along that path lies not only self-delusion of the Osama Bin Laden sort but also the political violence that pathetic neediness begets.

But that world is gone, and that America is gone. What has replaced both is something far better, full of far more freedom, acceptance, diversity, and tolerance that what came before - yes, even despite our predictably frightened behavior of the past few years.

That new world/new America simply requires new and better skills. And the coronavirus is just another experience that will generate, teach, and codify those lessons and skills.

And it will make all of us, our nation, and this world stronger (or, if you must insist - greater).

System Perturbation,

System Perturbation,  globalization | in

globalization | in  Blast From My Past |

Blast From My Past |  Email Article |

Email Article |  Permalink |

Permalink |  Print Article

Print Article  Friday, March 13, 2020 at 12:09AM

Friday, March 13, 2020 at 12:09AM

Here's the chart:

Find the story about this chart here.

When I saw it, I thought, that looks like a lot of the charts I did way back when I ran a series of high-level USG workshops at the Naval War College (and elsewhere, like WTC1) for the DoD.

First, the notion of generically modeling the event:

A Process View of Y2K

"Y2K--The Event" will feature a distinct build-up phase (already begun), a peak period we consider "THE crisis," and an "end" phase in which the crisis unwinds either by its own accord or, more likely, by decree. Either governments will declare that the "crisis has passed" or some other crisis will arise and capture our attention. Slide 2 below presents another way of thinking through the process of Y2K's build-up, unfolding, and end.

Slide 2: A Process View of Y2K

The vertical axis of Slide 2 speaks to Network Instability/Failures, meaning the sorts of computer and network failures we've all experienced in our daily lives. The horizontal axis offers a timeline from 1998 to 2001.

As we move from left to right, the relatively low level of network instability and/or failures that we show for 1998 represents life as we know it--i.e., computers and networks break down with a certain frequency that we have come to know and accept. A big part of that acceptance is the "rule set" we have developed for dealing with these failures, such as "Always check by phone if the pager seems down," or "Always follow up with a phone call when the e-mail doesn't seem to go through." We'll call these familiar rules of thumb the "old rules," which we've developed as workarounds for familiar failures. These are our effective coping mechanisms, to use a psychological term.

The key uncertainty for 1999 is the extent to which the level of network instability/failures begins to rise over the course of the year as we get closer to dateline 010100 (six digit code representing the first day of January, 2000, as in, ddmmyy). If Y2K turns out to be a significant experience, then at some point in late 1999 or perhaps the first few days of 2000 the frequency and/or severity of the network instability and/or failures will reach some unknown threshold past which the "old rules" will no longer seem to apply. At that point, society would--in effect--develop a "new rule set," or "new rules" that apply to the dramatically altered parameters of the perceived crisis situation--however defined.

Our project is largely concerned with uncovering and understanding the potential "new rule set" that would ensue if Y2K, when combined with the Millennial Date Change Event, turns out to cause a significant and unprecedented rise in network instability for an extended period of time. Now, we can debate what the word "extended" means, but for our analytical purposes, it would be a length of time that exceeds what a reasonable citizen might expect in terms of network, economic, social, and government service disruptions arising from the "3-day snowstorm" measure that many advocate as a planning parameter for Y2K. Any unfolding of Y2K that doesn't create a lengthier array of significant disruptions for any area, country, or region, is unlikely to generate a "new rule set."

Finally, once the Y2K Event plays itself out (signified in the slide by the break in the chart line) and the failure/instability rate begins to decline, the question in terms of Y2K's long-term legacy is whether or not we return to the "old rules" associated with the previously understood standard of network instability, or whether we settle in on some "changed rule set" engendered by our experiencing of the Y2K Event. In large part, that will depend on the extent to which we come to understand Y2K as either a one-time event unique in human history or a preview of what "network instability" (and its associated crises) may evolve into as we move ever deeper into a period of history where individuals, communities, countries, and regions of the world become more interconnected and interdependent. In short, if globalization and networking represent the future, maybe Y2K has far more to teach us about that future than we might think if we view it as nothing more than the "last stupid act of the 20th Century."

The seriously unknown threshold on coronavirus, per the chart, is any nation's healthcare system capacity - a line drawn differently everywhere you go.

Then the models of Y2K onset:

III. A Series of Y2K Onset Models

Explaining Our X-Y Axis

Our X-Y Axis (shown below as Slide 4) begins with two simple questions:

- Horizontal axis asks the "What?" question: What is the nature of the Y2K Event?

- Vertical axis asks the "So What?" question: What is the impact of the Y2K Event?

There is a huge difference between these two questions, for the first question focuses on cause, while the latter focuses on effect.

One way we like to differentiate between the two questions is to employ a medical analogy. Think of the horizontal axis (What? question) as the nature of the trauma or illness and the vertical axis ("So What? question) as the patient's overall health. Two extreme examples show why this analogy is illuminating:

- Example 1 is an elderly man who is stricken with a very slow growing bladder cancer. While this elderly man could have lived with this cancer for several years, the stress of his hospitalization, exploratory surgery, and the frightening diagnosis stresses his already fragile system to the point where he suffers a stroke and is dead within two weeks as a result of major organ failures cascading throughout his system. To sum up, while the initiating event (bladder cancer) was more minor than major (placing it on the left side of the horizontal access below), the man's overall system robustness was weak (placing him on the lower side of the vertical axis). The medical outcome was--irrespective of its modest origins--disastrous.

- Example 2 is a two-year-old child struck with a very aggressive kidney cancer that--by the time of diagnosis--has spread to both her lungs. Other than that, though, the child is in excellent health, and as such, is more than able to survive the surgeries, radiation, and months of chemotherapy with no lasting negative effects of clinical value. To sum up the child's case, while the initiating event (kidney cancer) was more major than minor (placing it on the right side of the horizontal axis), the child's overall system robustness was strong (placing her on the higher side of the vertical axis). The medical outcome was--again, irrespective of its profound origins--quite positive.

These two very different medical case histories, drawn from the author's family history, highlight the importance of juxtaposing the "What?" and "So What?" questions to create the four quadrants of the X-Y axis, for it is not enough simply to ask how bad Y2K may be. Given how bad it may be (i.e., how many computerized systems fail), Y2K's ultimate impact will depend greatly on the targeted system(s) in question.

Looking at Slide 4, we then explain our X-Y Axis as follows:

- The horizontal axis, asking the "What?" question of the Y2K Event, posits the minor extreme on the left as being "Y2K events are discrete and episodic" and the major extreme on the right as being "Y2K event is widespread and sustained."

- The vertical axis, asking the "So What?" question of Y2K's impact, posits the minor extreme on top as being "Systems are robust," and the major extreme on the bottom as being "Systems are vulnerable."

Two caveats are in order:

- By "Y2K Event(s)," we refer only to network failures directly attributed to Y2K or those caused via subsequent cascading system failures, to exclude any social, economic, or political responses that exacerbate or reduce failure rates.

- By "Systems," we refer not only to a country's network systems (broadly defined to mean any network that moves something--e.g., bytes, people, electricity), but also its political, economic and social systems, with the key attributes of robustness being:

- Distributiveness

- Recovery capacity

- "Workarounds" capacity

- Trust "capital."

Having defined the extremes of our axes, we break down the four quadrants in the following manner:

- Best Case is when Y2K events are discrete and episodic and systems are robust

- Next Best Case is when the Y2K event is widespread and sustained, but systems are robust

- Next Worst Case is when Y2K events are discrete and episodic, but systems are vulnerable

- Worst Case is when the Y2K event is widespread and sustained and systems are vulnerable.

Slide 4: The X-Y Axis for Y2K Onset Models

Y2K Onset Model #1: The Ice Storm

The Ice Storm onset model is depicted in Slide 5 below.

In the embedded chart, the vertical axis defines a "field of Y2K failures," meaning we're not going to offer any percentages or "hard numbers" here, just a rough notion of overall failure saturation. Along the vertical axis we display the years 1999 through 2001, with the months of 1999 noted in solid-line marks and the months of 2000 noted in dashed-line marks. The difference between the two markings is meant to suggest that while we may feel we have a firm grasp of appropriate time units for the timeline leading up to 010100, perceptions of time's passing once we pass through the 010100 threshold may vary greatly depending on locale. For example, the subjective time unit of note for Wall Street at the beginning of January may be the first day of trading--a mere several hours' time, whereas the subjective time unit of note for a sheep herder in a less developed country may be as long as until the first time he brings his sheep to market--possibly several weeks.

Slide 5: The Ice Storm Onset Model

The Ice Storm onset model offers the classic, TEOTWAWKI view of Y2K: it hits en masse on or about 010100 and strikes virtually every aspect of society. To the extent that such a model may seem to hold true on a perceptual basis in any one locality or region (meaning, for all practical purposes, it seems as though all systems are impacted to some disabling degree), we posit that the Ice Storm's components are logically broken down into three categories:

- Direct Y2K failures

- Cascading system failures resulting from the direct failures

- Iatrogenic crisis management or social responses that exacerbate the cascading failures or trigger new threads.

While this model held implicit sway during much of the Y2K debate in 1998, it has receded in prominence over the course of 1999, as remediation efforts make clear that this is not a useful universal model. Having said that, however, we believe the model retains great validity for understanding pockets of significantly damaging Y2K impact that may occur around the world, meaning those areas where--for all practical purposes--the TEOTWAWKI notion may well emerge among significant portions of a population battered by widespread network failures.

Of course, even here we're still talking only about the perceived onset, and not some sustained environmental status that would realistically drag on for months. As such, the key question for the Ice Storm onset model is, "How fast can the society or economy in question recover by necking down the failure rate to some level commensurate with reasonably sub-optimal functioning (meaning, for many around the world, the return to "life as we know it")?"

Y2K Onset Model #2: The Flood

The Flood onset model is depicted in Slide 6 below.

Slide 6: The Flood Onset Model

The Flood onset model depicts a slow but inexorable bulge of network failures that first rises above the usual "background noise" level on or about 010100 and then expands for something in the range of the first six months of 2000, peaking near the end of the 2nd Quarter or at some point in the 3rd Quarter. In some ways, we could suppose the same breakdown of elements (direct, cascading, iatrogenic) here as with the Ice Storm model, but because of the greatly extended timeline (thus allowing for more effective crisis management and network triage), we limit our description here to direct and cascading network failures, thus positing a peak failure rate somewhere in the range of 50 percent of all networks.

As such, the Flood model gets nowhere near the TEOTWAWKI pain range, but instead describes something more akin to a significant economic downturn, most likely corresponding to popular perceptions of a recession or financial market "correction." In that manner, the Flood model possibly describes a more profound economic impact than the Ice Storm, which, while it is a shock to the system, is probably of shorter duration. So, like the Ice Storm, the Flood model involves an interrelated sequence of network failures, albeit with a far smaller immediate impact on the overall functioning of society.

In keeping with the weather analogy, the key question for the Flood model is, "What constitutes a 'low-lying area?'" One example of a potential low-lying area would be manufacturing, whose network failures would not likely be centered on the 010100 threshold, but rather build up over time as production continued throughout 2000. Another could be medical supplies, especially the production and distribution of key pharmaceuticals. Still another might be the processing and distribution of clean drinking water.

Y2K Onset Model #3: The Hurricanes

The Hurricanes onset model is depicted in Slide 7 below.

Slide 7: The Hurricanes Onset Model

The Hurricanes onset model presents a series of sectorally-limited (meaning unconnected across sectors) but relatively lengthy (meaning some cascading effect) constellations of network failures. In effect, this model is a hybrid of the Ice Storm and Flood models. The Hurricanes model packs the same immediate punch as the Ice Storm model, albeit in isolated "low-lying areas" (echoing the Flood model), thus limiting the overall impact on the functioning of a society.

The Hurricanes model speaks more to the "winners and losers" approach to thinking about Y2K's ultimate impact: some sectors of society will seemingly get off scot-free, while others will seemingly suffer great damage. The key difference with the Flood model is the lack of interrelation and simultaneity, so rather than employing the economic language of "downturns," we're more likely to describe "shake-ups" in one or another industry.

The same approach to identifying vulnerable sectors that one uses with the Flood model would apply here, although in an overall sense, the Hurricanes model is probably best used to think about countries whose remediation efforts have been weak, for here we run into the notion of over-confidence possibly leading to poor crisis management preparation. If such "poor remediators" turn out to be far more vulnerable than they realize, then the key question becomes, "How can coordinated triage and crisis management avert the appearance of a critical mass of substantial--yet still relatively isolated--network failure clusters?"

Y2K Onset Model #4: The Tornados

The Tornados onset model is depicted in Slide 8 below.

Slide 8: The Tornados Onset Model

The Tornados onset model refers to a "season" of sectorally- and temporally-limited Y2K-induced network failures. This model is the closest to a null hypothesis of Y2K's overall impact, for, in many ways, it describes life as we know it, albeit with a higher-than-average failure rate. The Tornados model can likewise be thought of as the "key dates" model, for the two go naturally hand-in-hand when one seeks real-world evidence of significant network failures that either produce serious disruptions of service or require extraordinary efforts at repair. For if such key dates come and go without displaying any significant failures, meaning they're so big they can't be hidden by the service providers in question, then these Y2K milestones pass by without registering significant values on any sort of TEOTWAWKI scale, becoming the Y2K equivalent of a "tree crashing in the forest when no one's there to hear it."

The "key dates" approach does correspond nicely with the Gartner Group's predictions of Y2K failure rates rising and falling over the course of 1999 and through the year 2001, but the big deficiency of this model to date has been the lack of any stunning failures on key dates that have already passed. For example, no failures featuring major negative impact occurred on 1 or 3 January, the first day and business day, respectively, of 1999. The start of many fiscal year programs on 1 April also failed to reveal any serious disruptions for the governments involved. The so-called "nines" problem that was slated to appear on 9 April likewise produced no failures of great societal value in any country around the planet. Most recently, the 1 July threshold came and went with no apparent damage to the 46 U.S. states whose fiscal years began that day.

Meanwhile, Cap Gemini America, the computer consulting firm, declares on the basis of their recent survey of Fortune 500 companies and a smattering of U.S. government agencies that close to three-quarters of the respondents report experiencing a Y2K-related failure through the first quarter of 1999. But if these firms are having these failures and none are making any headlines, how is that much different from everyday life as we know it? Aren't private firms and government agencies experiencing network problems on a fairly regular basis, and just as regularly keeping such failures under wraps? The key missing data involve how much different 1999 is turning out to be compared to any previous year, meaning what is the "instability added" from Y2K? And that's the data we haven't found anywhere yet.

Having said that, the key question for the Tornados model remains, "What constitutes good learning over time?" For example, should our confidence grow due to the lack of Y2K headlines stemming from the key dates already passed? Or should we ignore most if not all of that success, especially for a pure fellow traveler such as the "nines" problem? After all, we can get fixated on Y2K key dates all through 1999, get through them all quite nicely, and still suffer significant tumult on 010100. Uneventful key dates make that seem less likely, but don't rule out it out by any means.

So far, it seems like we're experiencing all four models to some degree:

Onset Models Leading to Generic Y2K Outcome Scenarios