Statement submitted

By

Dr. Thomas P.M. Barnett,

Senior Managing Director,

Enterra Solutions

LLC

To

Seapower and Expeditionary

Forces Subcommittee,

House Armed Services

Committee,

United States Congress

26 March 2009

I appear before the subcommittee today

to provide my professional analysis of the current global security environment

and future conflict trends, concentrating on how accurately--in my

opinion--America's naval services address both in their strategic

vision and force-structure planning. As has been the case throughout

my two decades of working for, and with, the Department of Navy, current

procurement plans portend a "train wreck" between desired fleet

size and likely future budget levels dedicated to shipbuilding.

I am neither surprised nor dismayed by this current mismatch, for it

reflects the inherent tension between the Department's continuing

desire to maintain some suitable portion of its legacy force and its

more recent impulse toward adapting itself to the far more prosaic tasks

of integrating globalization's "frontier areas"--as I like to

call them--as part of our nation's decades-long effort to play bodyguard

to the global economy's advance, as well as defeat its enemies in

the "long war against violent extremism" following 9/11. Right

now, this tension is mirrored throughout the Defense Department as a

whole: between what Secretary Gates has defined as the "next-war-itis"

crowd (primarily Air Force and Navy) and those left with the ever-growing

burdens of the long war--namely, the Army and Marines.

It is my sense that the current naval

leadership views the global environment with great accuracy, understanding

its service role to be one of balancing between four strategic tasks:

a) sensibly hedging against the slim possibility of great-power war;

b) preparing the force for high-end combat operations against a regional

rogue power armed with nascent nuclear weapons capacity; c) supporting/conducting

ground operations in the struggle against violent extremism; and d)

improving maritime governance and security in those regions where today

it remains virtually non-existent (e.g., most of Africa's coastline).

Using the vernacular of my published works*, I consider the

first two tasks (great-power war, war against regional rogues) to fall

under the rubric of America's Leviathan** or big-war force,

while the latter two tasks (struggle against extremism, extending governance)

define the growing portfolio of our nation's System Administrator*

or small-wars force.

Historically, the Department of Navy

defined the totality of our nation's would-be System Administrator

force, meaning, prior to the World Wars of the 20th century,

it was the job of the Navy and Marine Corps to both defend and extend

America's commercial networks with the outside world, while the U.S.

Army (i.e., Department of War) served mainly as a continental constabulary

force that worked to integrate western frontier lands. Those World

Wars, in combination with the Cold War, transformed the U.S. Army and

its offshoot, the Air Force, into the

primary Leviathan services vis-à-vis the Soviet threat, while the naval

services, despite the grand ambitions of their 1980s Maritime Strategy,

were left overwhelmingly in the role of managing the adjacent theaters

known as the Third World. At Cold War's end, those naval forces

gladly embraced their enduring "SysAdmin" role, portraying themselves

as de facto global police capable of handling--on their own--virtually

all developing-region crisis scenarios short of regional war.

But with the post-9/11 interventions (Iraq, Afghanistan), the Navy quickly

saw its global constabulary role eclipsed by the U.S. Army, as that

force, supported by the Marines, once again stepped into its pre-20th-century

role as our nation's primary nation-building /occupational/counterinsurgency

force--this time on the shifting frontiers of globalization's advance.

Now, the Navy finds itself split between

preserving its blue-ocean Leviathan fleet while simultaneously expanding

its green/brown-water SysAdmin fleet, the former speaking primarily

to 20th-century great-power war scenarios that have lingered

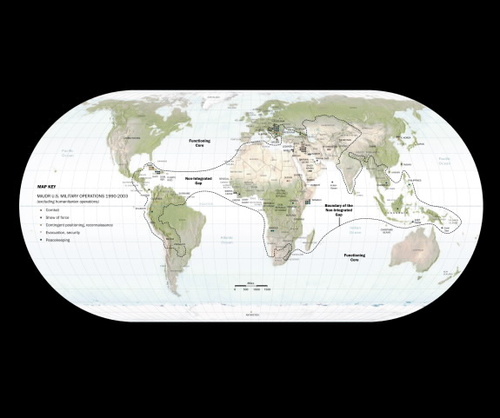

despite globalization's deep, pacifying embrace (see my geographic

definition of globalization's Functioning Core* in Figure

1 below), while demand for the latter only increases because

of globalization's historically swift penetration of a raft of previously

off-grid, still largely traditional regions (my definition of globalization's

Non-Integrated Gap**) where today we locate virtually all

of the wars, civil wars, genocide and ethnic "cleansing," mass rape

as a tool of terror, children lured or forced into combat activity,

acts of terrorism, exporters of illegal narcotics, UN peacekeeping efforts,

and 95 percent of U.S. military overseas interventions since 1990.

Figure 1: The Pentagon's

New Map (2004)

As someone who helped write the Department

of Navy's white paper, ...From the Sea, in the early 1990s

and has spent the last decade arguing that America's grand strategy

should center on fostering globalization's advance, I greatly welcome

the Department's 2007 Maritime Strategic Concept that stated:

United State seapower will be globally

postured to secure our homeland and citizens from direct attack and

to advance our interests around the world. As our security and

prosperity are inextricably linked with those of others, U.S. maritime

forces will be deployed to protect and sustain the peaceful global system

comprised of interdependent networks of trade, finance, information,

law, people and governance.

Rather than merely focusing on whatever

line-up of rogue powers constitutes today's most pressing security

threats, the Department's strategic concept locates its operational

center of gravity amidst the most pervasive and persistently revolutionary

dynamics associated with globalization's advance around the planet,

for it is primarily in those frontier-like regions currently experiencing

heightened levels of integration with the global economy (increasingly

as the result of Asian economic activity, not Western) that we locate

virtually all of the mass violence and instability in the system.

Moreover, this strategic bias toward

globalization's Gap regions (e.g., a continuous posturing of "credible

combat power" in the Western Pacific and the Arabian Gulf/Indian Ocean)

and SysAdmin-style operations there makes eminent sense in a time horizon

likely to witness the disappearance of the three major-war scenarios

that currently justify our nation's continued funding of our Leviathan

force--namely, China-Taiwan, Iran, and North Korea. First, the

Taiwan scenario increasingly bleeds plausibility as that island state

seeks a peace treaty with the mainland and proceeds in its course of

economic integration with China. Second, as Iran moves ever closer

to achieving an A-to-Z nuclear weapon capability, America finds itself

effectively deterred from major war with that regime (even as Israel

will likely make a show--largely futile--of delaying this achievement

through conventional strikes sometime in the next 12 months).

Meanwhile, the six-party talks on North Korea have effectively demystified

any potential great-power war scenarios stemming from that regime's

eventual collapse, as America now focuses largely on the question of

"loose nukes" and China fears only that Pyongyang's political

demise might reflect badly on continued "communist" rule in Beijing--hardly

the makings of World War III.

As the Leviathan's primary warfighting

rationales fade with time, its proponents will seek to sell both this

body and the American public on the notion of coming "resource wars"

with other great powers. This logic is an artifact from the Cold

War era, during which the notion of zero-sum competition for Third World

resources held significant plausibility primarily because economic connectivity

between the capitalist West and the socialist East was severely limited.

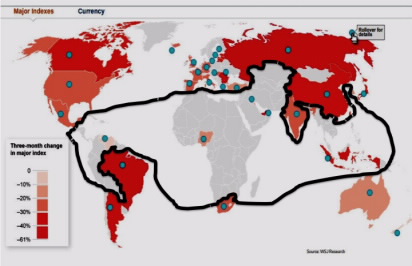

But as the recent financial contagion proved, that reality no longer

exists (see Figure 2 below). The level of financial interdependence

across globalization's Functioning Core, in addition to the supply-chain

connectivity generated by globally integrated production lines, renders

moot the specter of zero-sum resource competition among the world's

great powers. If anything, global warming's long-term effects

on agricultural production around the planet will dramatically increase

both East-West and North-South interdependency as a result of the emerging

global middle class's burgeoning demand for higher caloric intake/resource-intensive

foodstuffs. To the extent that rising demand goes unmet or Gap

regions suffer significant resource shortages in the future, we are

exceedingly unlikely to see resumed great-power conflict as a result.

Rather, we are likely to witness even more destabilizing civil strife

in many fragile states (a situation to which even rising great powers

such as Brazil, Russia, India and China could return under the right

macro-economic conditions), thus additionally increasing the SysAdmin

force's global workload and triggering further Pentagon resource shifts

from the underutilized Leviathan force. Naturally, the same could

be said about the legacy of today's global economic crisis.

Figure 2:

Initial market declines during 2008 global financial crisis, Core-Gap

superimposed

(Source: Wall Street Journal, 13

October 2008)

In sum, I see a future in which the

SysAdmin side of the ledger (more Green than Blue) experiences continued

significant growth in its global workload, while the Leviathan (more

Blue than Green) experiences the opposite. As such, the U.S. Government's

ongoing budget woes, in combination with the rising costs associated

with equipping the Leviathan force (e.g., incredibly expensive capital

ships), means that the Leviathan's platform numbers will shrink significantly

over the next couple decades while the SysAdmin's numbers (a cheaper

mix of smaller and more disposable/unmanned platforms) will rise dramatically--along

with personnel requirements (already seen with the move to add 92,000

ground troops). As a result, America's "soft power"

military resources will grow in size and capabilities, over time generating

pressure to create some new bureaucratic entity more operationally in

line with such activities--namely, somewhere between our current departments

of "peace" (State) and "war" (Defense).

As for the Department of Navy's current

force-structure plan, I think it's safe to say that our naval Leviathan

force enjoys a significant--as in, several times over--advantage

over any other force out there today. As such, our decisions regarding

new capital ship development and procurement should center largely on

the issue of preserving industrial base. My strategic advice is

that America should go as low and as slow as possible in the production

of such supremely expensive platforms, meaning we accept that our low

number of per-class buys will be quite costly. To the extent that

ship or aircraft numbers are kept up or even expanded in aggregate,

I believe such procurement should largely benefit the SysAdmin force's

need for many cheap and small platforms, preferably of the sort that

can be utilized by our forces for some suitable period of time and then

given away to smaller navies around the world to boost their own capacity

for local maritime governance. In other words, we should increasingly

make our overall naval force structure symmetrical to the now-asymmetrical

challenges and threats found in globalization's frontier regions (what

I call the Gap), our long-term focus being on increasingly the capacity

of states there to govern those spaces on their own.

As such, I am a firm believer in Admiral

Mike Mullen's notion of the "1,000-ship navy" and the Global Maritime

Partnerships initiative, especially when, as a part of such efforts,

our naval forces expand cooperation with the navies of rising great

powers like China and India, two countries whose militaries remain far

too myopically structured around border conflict scenarios (Taiwan for

China, Kashmir for India). America must dramatically widen its

definition of strategic allies going forward, as the combination of

the overleveraged United States and the demographically-moribund Europe

and Japan no longer constitutes a global quorum of great powers sufficient

to address today's global security agenda.

To conclude, the U.S. Navy faces severe

budgetary pressures on future construction of traditional capital ships

and submarines. Those pressures will only grow as a result of

the current global economic crisis (which--lest we forget--generates

similar pressures on navies around the world) and America's continued

military operations abroad as part of our ongoing struggle against violent

extremism. Considering these trends as a whole, I would rather

abuse the Navy--force structure-wise--before doing the same to either

the Marine Corps or the Coast Guard. Why? It is my professional

opinion that the United States defense community currently accepts far

too much risk and casualties and instability on the low

end of the conflict spectrum while continuing to spend far too much

money on building up our combat capabilities for high-end scenarios.

In effect, we over-feed our Leviathan force while starving our SysAdmin

force, accepting far too many avoidable casualties in the latter while

hedging excessively against theoretical future casualties in the former.

Personally, I find this risk-management strategy to be both strategically

unsound and morally reprehensible.

As this body proceeds in its collective

judgment regarding the naval services' long-range force-structure

planning, my suggested standard is a simple one: give our forces

fewer big ships with fewer personnel on them and many more smaller ships

with far more personnel on them. As the Department of Navy

finally gets around to fulfilling the strategic promise of systematically

engaging the littoral ... from the sea, doing so in complete

agreement--in my professional opinion--with the security trends triggered

by globalization's tumultuous advance, I would humbly advise Congress

not to stand in its way.

Return to Article

Return to Article