Recasting the Long War as a Joint Sino-American Venture

Thomas P.M. Barnett

Baker Center Journal of Applied Public Policy

Fall, 2007, pp. 34-44.

In this so-called long war against the global jihadist movement, the Bush administration’s greatest failure has been its lack of strategic imagination. It has added the right enemies to our to-do list, but failed to enlist the necessary new allies, giving our people the misperception that it’s America against the world.

This need not be the case. Our natural allies are now located on the frontiers of globalization, or among the three billion-plus new capitalists who joined global markets over the last generation, chiefly among them the Chinese.

The integrating core of globalization—namely the old West plus the emerging markets of the East and South—have effectively outsourced the global policing function to the United States by refusing to balance our immense warfighting and power projection capabilities with their own. Instead, Western Europe focuses on economically integrating the former Soviet bloc, while rising titans like China and India, for reasons of rising energy requirements, focus overwhelmingly on integrating—on relatively narrow terms—resource providers located in those regions least connected to the global economy, or what I call globalization’s non-integrating gap (e.g., the Caribbean rim, Africa, the Middle East, Central Asia, and the southeast Asian littoral states).

Not surprisingly, the Pentagon’s new map in this long war corresponds greatly to those gap regions, for there we find the preponderance of “moderate” dictators, rogue regimes, and failed states, all of whom either attract the attention of transnational terrorists or support their activities for their own nefarious reasons. Viewed in this light, our victory is logically defined as the successful building out of globalization’s core and the simultaneous shrinking—or successful economic integration—of those gap regions. As we’ve seen in Afghanistan and Iraq, this is no mean task and one that generates significant labor requirements.

So I say, locate the labor where the problem is.

A New Strategic Value Proposition

America has the wherewithal to wage any conventional wars necessary to defeat traditionally arrayed enemies (i.e., militaries). But in today’s “flat world” competitive landscape, war’s just the first-stage defensive acquisition. Real stability comes only after the second-stage postwar merger that extends globalization’s broadband connectivity to the previously disenfranchised masses and—yes, Virginia—exposes all that cheap labor to “exploitation” by outside capital that typically pays significantly higher wages than the local economy can muster.

Let me give you my definition of the value proposition here and see if it doesn’t make sense.

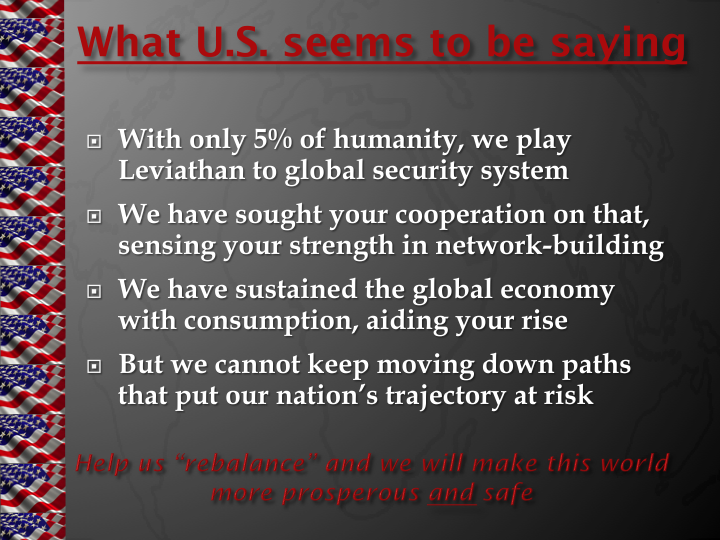

America’s got a first-half offering without peer: a Leviathan with an unparalleled capacity for war-making and the unspoken power of deciding when other states can make war themselves. What we lack is a credible second-half offering, or what I’ve dubbed a “system administrator” force capable of winning the peace through effective stabilization and reconstruction operations. Ultimately, this force needs to be more civilian than uniformed military, and fueled more by private sector investment than public sector aid. It also can’t be an American-only operation. The Bush administration’s big mistake in Iraq was telling allies, “If you’re not tough enough to show up for the war, don’t show up for the peace, and forget about any contracts!”

Based on our efforts to date in this long war, America currently fields a first-half team in a league that insists on keeping score until the end of the game. We lost less than 150 personnel in the Iraq “war” (major combat operations). We’ve lost more than 2,000 in the “peace” (postwar) that hasn’t quite followed.

So yeah, it matters.

Right now, our enemies in this long war field a better, more capable version of the sysadmin force than we do. Don’t believe me? Then you haven’t been paying attention to new entrants to the market like Hamas and Hezbollah, two tribe-building enterprises that excel at the second half while not even trying to compete in the first half, as Israel recently discovered in Lebanon and the West Bank to its growing regret.

So if the gap’s new entrants to the postwar market should be sizing our sysadmin force (just like the Soviets once sized our Leviathan force during the Cold War), it seems clear who should be increasingly populating the core’s second-half team today: new entrants to globalization’s “systems integration” market such as China and India.

Think about that for a minute. Stability and reconstruction operations associated with postwar and post-disaster environments require lots of bodies, both in terms of uniformed boots on the ground and relatively cheap labor to lay down all that necessary infrastructure—both hard (physical) and soft (institutional). China and India both have million-man armies, as well as a long-demonstrated willingness to send their best and brightest (along with their most desperate) civilians the world over in search of economic opportunity (e.g., “non-resident Indians” are outnumbered only by the multitude of “overseas Chinese”).

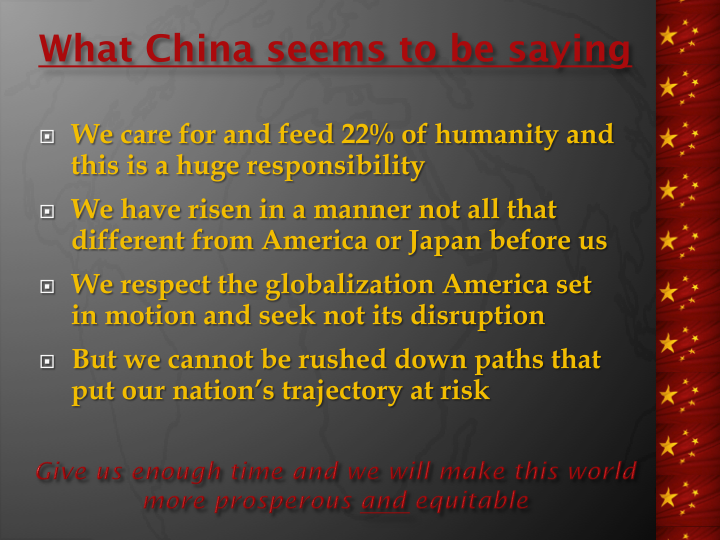

More to the point, the best nation-building brand out there right now is the Chinese model. I know, I know, it doesn’t meet our threshold definitions of democracy and human rights (not to mention coming nowhere near our EPA standards), but it sure as hell beats America’s post-Cold War product line of Somalia, Haiti, Afghanistan and Iraq. Let’s be honest: China’s leveraged buyouts, as mercantilist as they are, beat our hostile takeovers—hands down.

And that just tells you how bad America’s military intervention “brand” has become. Emerging from World War II, the world believed that an American invasion was a fundamentally good thing, or something that got you tons of aid and propelled you to the top of the pile (e.g., West Germany, Japan, South Korea). Back then there was no shortage of “mice” that wanted to “roar” for our attention, but somewhere along the way, probably thanks to the influence of nuclear weapons on our military strategy, we lost that second-half skill set, probably because it seemed pointless in a world perverted by the looming threat of mutually-assured destruction. So, starting with Vietnam, where we first displayed our sad combination of increasing ineptitude at, and discomfort with, the second-half game, our brand has suffered a precipitous decline.

So why not turn to the original market-maker in the field of “revolutionary war,” otherwise known as the People’s Republic of China? If we face a future of insurgents and what the our military calls “fourth-generation war” (in which our enemies seek to deflate our will rather than defeat our forces), why not ally ourselves with the best counter-insurgency model operating in those gap regions today, one that effectively—and rather preemptively—woos both dictators and failed states alike?

Put another way, you can invade the country and then start up your counter-insurgency/reconstruction ops (the American route), or maybe you might just co-opt the major players pre-conflict with investment offers they can’t refuse (the Chinese route). So maybe it’s not always the case that if you want it bad, you get it bad.

Don’t get me wrong. I’m not advocating America continues its whack-a-mole approach to regime-toppling interventions inside the gap, only to turn over the aftermarket opportunities to the Chinese . . . uh . . . actually, I’m coming uncomfortably close to saying just that. I just believe that if we combined our chocolate (military interventions with a moral compass) with China’s peanut butter (economic interventions with a practical mindset), we might actually come up with a whole superpower, or basically a joint offering that finally covers the market—as in, defeats our political enemies while connecting the economically disenfranchised.

I’m asking you to come to the inescapable conclusion that America under the Bush-Cheney management team has become an un-sellable global brand in a market (modern globalization) that we made. That’s just wrong.

It’s wrong because it gets our people needlessly killed and because our interventions end up leaving the targeted state more disconnected from globalization than we found it (or worse, increasing its negative connectivity in the form of criminal and terrorist ties), meaning we’re not making the world a better place and we’re discrediting ourselves in the process.

So I’m asking you to invest in something better, or what I think will truly answer the mail in this long war—a full-service superpower that can wage both war and peace effectively. Combine the United States, a seemingly unprincipled Leviathan willing to invade anywhere inside the gap, with China, a seemingly unprincipled sysadmin willing to invest anywhere inside the gap, and I believe you’re looking at a superpower built whole, a long war legitimately won, and a globalization made truly global.

Now let me take you through the prospectus.

Less Clausewitz, More Sun Tzu

We know full well that America can defeat any traditionally arrayed opponent in major combat operations, known as “phase 3” in Pentagon parlance. But both Afghanistan and Iraq show that we’re simply not up to snuff in “phase 4” operations, otherwise known as the postwar. As we’re not credible in the postwar, our enemies have simply ceased fighting us in the war, knowing that a persistent postwar insurgency can defeat an impatient superpower. If your enemy’s goal is simply to kill 3 or 4 of your personnel a day and he’s willing to throw virtually unlimited labor at that goal, you’re going to lose over the long haul unless you figure out how to deny him ready access to his labor pool. That means jobs are our exit strategy.

Run into this savvy fourth-generation-warfare (4GW) competitor enough times and the American public will inevitably tire of engaging in any major combat operations, sensing a pointlessly ineffective postwar outcome. When that happens, our enemies in this long war have achieved an effective lock out, fencing off the roughly two billion people in these gap regions for their version of fundamentalist isolation.

Get good at phase 4 operations, however, and not only are your war threats made credible, but likewise your up-front offers of—for lack of a better phrase—pre-canned bankruptcies for failing regimes. I mean, why not make a pre-emptive bid instead of launching a pre-emptive war? By doing so, we turn on its head Karl von Clausewitz’s famous definition of war as “ . . . continuation of politics by other means.”

Inside the Pentagon, strategists describe this goal as getting so adept at phase 4 operations that you can wage them up front, in the pre-crisis period known as “phase 0.” At this point, you’re in Sun Tzu’s preferred venue, and your battles are won long before shots are fired. You’re basically the peacekeeper and infrastructure builder who shows up before the crises boil over, effectively keeping the situation just cool enough to avoid a major military intervention. Think of it as limited-liability nation building.

Imagine the Iraq scenario this way: according to insider accounts, the Arab League convinced Saddam Hussein to agree to go into exile and avert a war months before the U.S.-led invasion occurred. In the end, Arab leaders abandoned the plan because of disputes among themselves over how it would have played out. No imagination required there: the region’s leaders were of many minds regarding the possibility of a real “cake walk” for the Americans. But consider this possibility: what if, at the right moment in that negotiation, a proposal is made for a consortium of Chinese, Indian and Russian elements (both governmental and private-sector) to run the postwar reconstruction? Imagine how the zero-sum sheen is rubbed off the potential American-dominated postwar occupation.

Then consider how the Chinese could have conducted the rebuilding of Iraq’s shattered infrastructure—on time and under budget. And then consider how President Bush’s “big bang” strategy (i.e., making post-Saddam Iraq a shining example of potential reform in the region) might have unfolded differently, primarily because popular expectations—both here and in Iraq—would have shifted from instant democracy to rapid reconnection to the global economy.

Seriously, do you think we’d have the same deprivations and lack of economic activity that fuel sectarian violence in Iraq today if we had picked the Chinese over the Coalition Provisional Authority? Or let me put it this way: could the Chinese have done any worse?

Do you find such a scenario implausible? Then you haven’t been paying attention to Africa recently. Anyone’s who done any business or peacekeeping in Africa in the past decade will tell you that the “China LLC” (with an emphasis on “limited”) is already up and running across most of the continent. For example, China recently became the 13th-largest provider of peacekeeping troops across gap regions, with a concentration in Africa (Congo, Liberia, Sudan) and a nascent portfolio in the Middle East (Lebanon) and the Caribbean (Haiti).

Chinese trade and aid throughout Africa has risen dramatically in recent years, to include a sandals-on-the-ground presence of 80,000 nationals. China’s goods are in every market, its vehicles ply every road (many of which are laid with Chinese funds and laborers), and its logistical and information networks are sprouting up everywhere valuable raw materials are found—especially oil.

Beijing recently hosted an unprecedented summit of 30 African leaders and guess what topped the agenda? It surely wasn’t the Bush administration’s soda straw view of globalization, otherwise known as the “war on terror.” Instead, the summit focused on debt relief, human resource development and training, investment and aid, and reduced trade barriers. Just survey America’s strategic debates concerning Africa today (“Do we intervene in Darfur with troops?” “Go back to Somalia to deal with the Islamists?” “Set up an Africa Command?”), and it seems clear: we’re stuck in a phase-3, Clausewitzian mindset while China’s winning early-stage, phase-0 contracts (and allies) in a way Sun Tzu would readily approve.

Whether we care to admit it or not, China effectively limits America’s strategic liability across Africa already. Sudan is a good example: many in the West want to criticize China’s large-scale investments in the nation’s infrastructure and oil industry. But quite frankly, absent the West’s interest in providing significant numbers of peacekeepers for Darfur, what China does in Sudan with its ongoing investments is limit our potential strategic liability.

In that forest, large branches may fall, but not the entire tree. So long as the latter does not occur, America hears nothing.

Cynical? Hell yes. But if we’re not going to beat ‘em, please don’t deny we’re implicitly joining them in this liability-limiting endeavor. As the world’s sole military superpower, America is the silent partner in every non-intervention the global community launches.

So No Rest For the Weary Leviathan

Let’s be honest about the capabilities at hand for solving Africa’s endemic conflicts (and they are so many). NATO (the Europeans) have basically “been there, done that” decades ago and exhibit little desire to return. Meanwhile, the African Union, the continent’s putative peacekeeping arm, is essentially the UN without the swagger (I know, hard to imagine). When the AU hit the ground in Darfur, for example, they quickly settled into a passive observation role, basically documenting the ongoing atrocities and little else (they shoot photos, don’t they?).

America needs to get real with itself. Africa is not ours and ours alone to ignore strategically, and it’s got to be so much more than just the experimental playground for Bono and the “two Bills” (Gates, Clinton). Tied down as we are militarily in the Persian Gulf, the U.S. shouldn’t look a gift horse in the mouth, because China’s effectively “prepping the battlefield” for us in Africa, and that’s where this fight heads next.

As the U.S. and its Western allies squeeze the balloon of the global jihadist movement currently centered in the Middle East, that balloon can expand in two directions: north into Central Asia and south into sub-Saharan Africa. This fight won’t go north simply because that region is surrounded by interested powers (e.g., Russia, Turkey, India, China) willing to do whatever killing is required to stop the spread of Al Qaeda’s influence—and yes, that includes Shiite Iran, no friend to the exclusively Sunni-derived radical Salafi movement currently fronted by Bin Laden.

So if it can’t go north, this fight’s heading south.

Frankly, it’s the combination of that inevitability plus China’s rising influence on the continent that drives the Pentagon to stand up an Africa Command (already in prototype in European Command’s Joint Task Force-Horn of Africa). But here we risk repeating the Bush Administration’s mistake of adding new enemies but no new allies. Instead of viewing China’s growing presence as a strategic complication, America needs to recognize it as a natural partnering opportunity.

Africa is enjoying an economic upswing, thanks in no small part to China’s rising resource draw. The continent’s business climate is improving dramatically, and about half of the world’s top-20 fastest growing economies can be found here. Hell, when American hedge funds start moving in, you know something’s brewing.

America has the sad tendency for viewing Africa primarily as an aid sinkhole, whereas maturing emerging markets like China view it as a logical target for future expansion. Yes, Beijing’s resource requirements drive everything for now, but think ahead to when China’s “inexhaustible” cheap labor supply dwindles due to higher production costs and a burgeoning middle class more focused on consumerism than savings. To whom does China outsource the low-end jobs while it scrambles up the production ladder? Clearly, Beijing will divert as many jobs as possible to China’s underdeveloped interior, and just enough to its neighbors to keep the regional peace, but eventually a good portion will flow to Africa, in large part to balance the very real imbalances created to date by China’s mercantilist trade profile.

There are plenty of China hawks in the Pentagon who are dead certain we’re headed for some military showdown with Beijing over Taiwan. But more of Wall Street is coming to the conclusion that our real competition with China is all about who makes the most markets in globalization’s gap regions. That makes Africa the logical ground zero in both the long war and this ever “flattening” global competitive landscape.

But you know what, this is exactly the kind of race America needs to be running.

Racing to the Bottom of the Pyramid

China today is not the market it was as recently as five years ago, when basically any foreign company and investment were welcomed with open arms, giving foreign multinationals control over roughly 60 percent of the country’s current exports. Today’s China sits atop a huge pile of domestic savings and approximately one trillion in U.S. reserve currency, giving it a confidence far distant from the fears barely suppressed during the Asian flu of the late 1990s. One way that confidence is expressed is increased developmental aid to trade partners, largely focused on accessing their raw materials.

As China becomes more outgoing in its foreign policy, however, its economic focus turns inward to a host of structural problems: its rickety financial sector, the imbalance between the booming coast and the dreadfully impoverished interior, and the rapidly aging population (no country in human history has ever aged as quickly as China will over the next three decades). Toss in the greatest migration in human history (internally, from rural to urban areas), and we’re talking about hundreds of millions of new consumers rapidly surfacing in China’s burgeoning middle class.

Thus, what was primarily an investment dynamic by which foreign companies rented China’s cheap labor for export creation now rapidly shifts into strategic alliances with rising domestic companies that Beijing not only positions to dominate the growing internal market but likewise plans on growing into successful global brands. This new inside-out growth strategy (i.e., domestic dominance leading to global dominance) is interpreted by many Western investors as a “nationalist backlash,” but as long-time China watcher Harry Hardin argued recently in the Wall Street Journal, this is a “marginal adjustment to, rather than a fundamental repudiation of, Beijing’s broader embrace of globalization.”

In short, China’s just wants to elevate its game.

The car industry is a good example. Western firms jumped into China years ago primarily to access the cheap labor on auto parts. But now, as China’s car market explodes (it’s already roughly the equivalent of the U.S. and European markets and soon to become the world’s largest domestic market), the strategy of such global giants as GM, Ford, Honda, and Volkswagen shifts from accessing labor to accessing customers. As Bill Ford Jr. recently told the Wall Street Journal, “We’re barely scratching the surface in China.”

There’s been a lot of hyperbole recently about how quickly Chinese automobile manufacturers can wedge themselves into the U.S. market as the third coming of Toyota and the second coming of Hyundai. But the real export opportunities in joint ventures with rising Chinese firms (e.g., Geely, Chery, Great Wall, SAIC) will appear first in other emerging markets and developing economies. It is in these lower-end markets that companies tap into what University of Michigan economist C.K. Prahalad dubs “the power at the bottom of the pyramid.”

That dynamic is important to consider as we contemplate the long-term integration of such gap regions as the Middle East, Africa, Latin America, and southeast Asia, especially as we retool our approach to postwar and post-disaster stability and reconstruction operations.

The problem is, when the rich, know-it-all Americans show up on the post-whatever scene, our tendency is to cost everything out at Six Sigma prices, when in reality, what’s typically appropriate is something on par with One or Two Sigma outcomes. We go for the grand and complex when the simpler and more robust usually works better in such austere environments. So it’s wireless, not landlines. It’s cell phones, not laptops.

Pricing out Africa’s integration at American prices makes no sense whatsoever. Africa is going to be a knock-off of India and China, which in turn can be considered knock-offs of Singapore and South Korea, which in turn can be considered knock-offs of Japan, Asia’s original knock-off of America. Think of it as a realistic “six degrees of integration.”

So gaining access to markets like China and India isn’t just an end in itself (i.e., cheap labor), even when investments subsequently penetrate the domestic market’s expanding opportunities. In the end, Western foreign direct investment into these new pillars of globalization’s core serves as a gateway to accessing the emerging-markets-after-next, or that next wave of infrastructure development found inside the very gap regions where this long war against radical extremism plays itself out.

Taken as a whole, the infrastructure building opportunities inside emerging markets—both existing and future—over the next three decades is considered by developmental experts as unprecedented in size. Asif Shaikh, CEO of International Resources Group, an international professional services firm specializing in developing markets, estimates that six trillion dollars of infrastructure will be built in the energy sector alone, with an additional four trillion dollars spent on water. Much of this work will occur in the twin pillars of China and India, so expect a roll-up of Western and local firms to create the multinational behemoths capable of handling this enormous flow of construction.

Then imagine what these resulting giants will be capable of accomplishing in postwar and post-disaster reconstruction environments in Africa and other gap regions.

The strategic importance of allying with Chinese and Indian firms is that they re-acquaint us with the twin realities of selling successfully to modest-wealth classes and building markets on globalization’s rough-and-ready frontiers, two skill sets many Western firms have essentially lost as our economies moved far away from such experiences. America’s last frontier, for example, closed over a century ago.

But it’s worth recollecting that market-making, frontier-integrating period known as the “settling of the American West,” because it reminds us of the intensely close relationship that once existed between our military and the private sector, something that was lost during the Cold War period, except in the rather closed club of the military-industrial complex. Now, as we look to postwar experiences in places like Afghanistan and Iraq, where new contractors galore have entered the nation-building market, it’s clear that the military-market nexus has once again become the centerpiece of our national security strategy—that is, if we’re serious about winning the long war.

Let me tell you, the Chinese are just as serious on this score as we are. To its credit, the Bush administration has spent a lot of time encouraging Beijing to become a “responsible stakeholder.” What the White House hasn’t done effectively is define—in a sufficiently expansive fashion—which stakes America truly shares with China.

An Offer They—and We—Can’t Refuse

Britain was smart enough at the start of the 20th century to hitch itself to the rising star in the West called America. That strategic mentoring role and resulting “special relationship” allowed the Brits to punch above their weight through three world wars (two hot and one cold). America faces a similar decision on China today: do we mentor Beijing into the halls of power or do we succumb to the realists’ predictions that war with the Middle Kingdom is inevitable in this “Pacific century”?

Britain went to war twice with fellow first-tier great power Germany in the first half of the 20th century and both were radically reduced to second-tier powers as a result, so I guess it all depends on how long America wants to remain a first-tier superpower. If the world isn’t big enough for a second one, then we’ve got a real problem. But is the world is ready for a superpower partnership . . . ?

The fact is, China’s already our silent partner in virtually every crisis spot around the globe. Want to fix Sudan? Better involve China. Want to tame Chavez? Better involve China. Want to economically isolate WMD-seeking Iran? Forget about it, because China and India (not to mention far-more-reliant-on-imports-Japan) have already made that call on both oil and gas. But help on taming Tehran? Under the right conditions, better involve China.

Then there’s Kim Jong Il.

It’s no secret that with the tie-down of American forces in Iraq we can’t do much of anything but bomb North Korea into the stone age, which—of course—would instantly trigger that which Beijing fears most: the mass flow of refugees north. So, in so many words (okay, just hearing Bush say the word “diplomacy” is enough), the Bush-Cheney team has let it be known that it would be fine by them if somebody rid them of this horrible man. You know, next time Kim’s train simply comes back empty.

Actually, the Chinese have studied the KGB-engineered fall of Nicolae Ceaucescu in Romania, going so far as to interview senior players there, so the concept of forcing Kim out from within is no joke. After all, Lil’ Kim runs a serious kleptocracy, and criminals can be flipped.

Then there’s what would be waiting on the far side of a united Korea: the makings of an East Asian NATO that rules out great power war on the continent. Simply put, it’s the biggest missing link in America’s current long war strategy, trapping—as it does—far too many of our military assets in a Cold War-era strategic posture.

But get an East Asian NATO set up and two things happen: 1) it frees up U.S. troops stationed there; and 2) we’re finally able to seriously tap the region’s trio of great powers (China, Japan, Korea) for military help in places where it’s more needed, like the Middle East and Africa. Finally, it’s important because, historically speaking, it’s not a good idea to have both Japan and China powerful at the same time without some sort of arrangement in place.

So what’s the state of our military-to-military relationship with China under the Bush administration?

In a word, guarded.

The Bush neocons came into power in 2001 obviously gunning for China. Remember the EP-3 spy plane incident off Hainan? Well, if Cheney and Rumsfeld hadn’t been interrupted by 9/11, that preview of the coming distractions would have been amazingly prescient.

Following 9/11, though, China fell off the Pentagon’s radar until . . . that is, when the most recent long-range planning cycle (2005 Quadrennial Defense Review) kicked into gear and many of the defense-industrial complex’s pet weapons systems and hugely expensive platforms were threatened by the ongoing operational costs (re: Iraq) of this long war. At that point, the China hawks went into overdrive and have stayed at that level since, cranking out warning after warning about China’s “huge” military build-up and how it threatens Taiwan and the rest of Asia.

How huge is that build-up? The highest estimates say that in twenty years China might be spending roughly half as much on its military as the U.S. spends on its military today! I don’t know about you, but I think our lead is safe for now. Plus, quite frankly, 85 percent of China’s arms purchases are from the Russians, so seriously, how bad can that be? Or did I miss something about who lost the Cold War?

Ah, but plenty of security experts will reveal—only on background, of course—that “if you only knew what I knew about Chinese attempts to [blank],” then you’d never even consider treating them as anything but globalization’s fifth column, just waiting to spring up and disable our entire economy with their cyber-jujitsu!

I say, it’s finally nice to have somebody surpass the Japanese and French in trying to steal our technology.

Seriously, every rising power in human history has sought to catch up to the leaders by engaging in persistent and pervasive economic espionage. America did it to the Europeans throughout most of the 19th century, begetting large portions of our industrial revolution in the process. Why should the Chinese be any different from the rest? The fact that they engage in such theft more over the Internet than the traditional route of sending their spies into our factories doesn’t make them unique. It makes them up-to-date.

Given all the situations where we’d like China’s help around the planet, the truly sad reality right now is that our military-to-military cooperation with the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) remains embryonic at best. For example, just as Kim Jong Il was popping his first nuke last summer, the U.S. Navy held its first-ever ship training exercise with a single Chinese naval vessel off the coast of San Diego. Seventeen years after the Berlin Wall and Tiananmen and that’s all we’ve managed.

Meanwhile, we’d love it if Beijing could somehow make Kim go away on its own, instantly shifting that security risk to China. I mean, talk about wanting to go all the way on the first date!

Outside of Asia, strategic risks are shifting against China, especially in the realm of energy security. Americans like to think we’re dependent on foreign oil drawn from unstable regions, but truth be told, we’re not. Roughly 70 percent of our imported oil comes from the Western hemisphere and Europe/Russia, with only 30 percent drawn from Africa and the Middle East (15 percent each), so that gives us a 70/30 split between stable/unstable sources, and those percentages aren’t predicted to change much in the future.

China, on the other hand, faces a riskier import profile over time. Today, China draws just over 40 percent of its imports from the less stable regions of Africa and the Middle East, but according to our Department of Energy, by 2030 that share will rise inexorably to almost 70 percent, making Beijing’s stability profile the mirror image of our own.

So it was no surprise to hear China’s top official on long-range energy planning recently propose that our two nations should come together to jointly explore, produce and—most importantly—protect energy sources in politically unstable regions.

You want China—as the Bush administration has long declared—to become a “responsible stakeholder” in global affairs? Well, Beijing just gave you a clear signal about which stakes matter most to China. Are we paying attention or just jerking knees?

When I go to Beijing and brief government and military long-range planners on these concepts, it’s easy to get a lot of warm smiles in reply. Hell, I’m making it sound like America’s got no choice but to partner with China all over these unstable regions. But you want to know how I quickly wipe smiles off those smug faces?

I tell them this: “For now, people inside the gap tend to equate globalization with Americanization, so we’re the bad guys they take hostage and blow up in the name of Allah and drive out of their lands to achieve their dream of civilizational apartheid. But know this, globalization is increasingly taking on a distinctly Asian flavor, with China firmly in the front, giving it a new face. Faster than you realize, you’ll see Chinese being taken hostage, Chinese being blown up, Chinese held up to the camera and having their heads cut off. And it’ll all happen because the radicals and extremists and jihadists and terrorists will inevitably come to this conclusion: the best way to drive off globalization is to drive off those infidel Chinese!”

Works every time.

Why? It’s one of the Chinese leadership’s greatest fears. That’s fundamentally why they keep such an amazingly low profile inside the gap despite the steep rise in their investments, peacekeeper deployments, and energy dependence. For now, America is the only place where fear of globalization equates to fear of China. But soon, that fear will spread to most of the planet, linking our two nations in the temptation common to all great powers: self-loathing.

Stuck in the Middle With Hu—For Now

The good news is, China’s self-limiting lack of self-confidence is going away as Beijing’s bosses experience a much anticipated generational shift from the so-called fourth generation (e.g., President Hu Jintao, Premier Wen Jiabao) to the far different fifth generation (the equivalent of our late Boomers, or roughly Barack Obama’s cohort born in early 1960s—like me).

China’s leadership generations go like this: Mao Zedong fronted the first generation of revolutionary giants (1949-1976), while the second (through the 1980s) was led by radical reformer Deng Xiaoping, who sent China down the path of markets and thus did more to shape our current world than any leader of the late 20th century. The third generation, helmed by Jiang Zemin, ruled China across the 1990s and right through 9/11. Jiang’s was the first generation of leaders trained abroad, overwhelmingly in the Soviet Union—birthplace of socialism. This was crucial, because the technocratic tinge of that formative experience made Jiang’s generation confident enough to extend Deng’s reform movement further, creating the “China Inc.” we know and fear today in global business.

The current leaders, known as the fourth generation, did not travel abroad for their education, trapped as they were in the nationwide insanity of Mao’s Cultural Revolution in the late 1960s. The result? A careful bunch of homebodies whose foreign policy consists of the soothing slogans (“peacefully rising China,” recently scaled back to “peacefully developing China” lest it seem too confrontational) and whose economic vision has turned increasingly inward to focus on the left-behind rural poor of the interior provinces.

So it’s not too surprising that America hasn’t gotten very far with Beijing recently in any seriously strategic dialogue: our neocons aren’t asking and their fourth-generation leaders aren’t listening. Toss in ever-paranoid Taiwan as the figurative third monkey holding his hands over his eyes (i.e., unable to see future integration with the mainland), and you’ve basically got the entire dysfunctional matched set.

But real change is just around the corner—and I’m not just talking about the 2008 American presidential election.

Next year the Chinese Communist Party will most likely pick from among the fifth generation pool the leaders who will assume the reins officially in 2012 but whose lengthy succession begins rolling out almost immediately. This generation may be known to many of you already, because whether you realize or not, you went to college with many of them in the late 70s and early 80s. So yeah, this crowd does get America. In fact, these guys get globalization better than our current leaders do, because China is so much closer—historically speaking—to the infrastructure build-out process associated with globalization’s Borg-like integration wave.

What’s so amazing about this next generation is how they look at the world: a Kantian naiveté bordering on Thomas Friedman (“Got McDonald’s? You’re in!”). But beyond that wide-eyed optimism there is a growing and rather steely awareness that, as Spiderman’s uncle famously intoned, “with great power comes great responsibility.” Having spent days in deep discussion with this crowd, I will tend you what impresses me most about them is their earnestness. They are perceptively shifting—echoing John F. Kennedy’s generational call—from thinking about what the world owes China to what China owes the world.

There’s not a moment to waste.

When I last sat down with PLA strategists, I told them their biggest challenge over the next decade or so is rebranding their military from “revolutionary warrior” to “globalization’s security guard” in support of China’s role as globalization’s general contractor in the great build-out to come. This repositioning of China’s global security profile must be approached carefully, setting up easy wins that mark the PLA as both competent in its execution and trustworthy in its presence—especially in partnership with U.S. military forces. A joint response to Asia’s 2004 Christmas tsunamis would have been a good opportunity. It worked for the Indian Navy, but China’s military was nowhere to be found.

Over time, the Pentagon and the PLA need to prove out this strategic alliance in a series of early-stage engagements—preferably in Africa—that demonstrate how market economies—both old and new—come together to shrink globalization’s gap. Yes, I realize that many in my country consider the cultural and political gaps between America and China to be insurmountable in any time frame worth mentioning, but in my opinion, that Cold War mindset plays into the strategic goals of the global jihadist movement, which wants nothing more than to pit a rising East against an aging West with radical Islam as the great balancer.

I say we deny Osama that dream—as soon as possible.

Rehabilitating failed states is a labor-intensive process, because postwar and post-disaster environments—our most likely traction points—simply demand it. When you have a body requirement, you go to body shops, locating the labor where the problem is.

In the Cold War, our strategic triad consisted of missiles located on land, at sea and in the air. In the long war, many Pentagon planners have taken to describing America’s new strategic triad as the Army, the Marines,and Special Operations Command.

No argument there.

But what I’m telling you is that, on an international scale, we’re looking at a strategic triad consisting of the United States, China, and India—the three million-man militaries out there today (once North Korea is liquidated). This is the sysadmin’s strategic triad that, when backed up by half the world’s economic power come 2026 (according to The Economist), makes the dream of shrinking globalization’s gap entirely feasible.

But, as always, the way ahead is determined by will as much as by wealth, and here is where America’s current leadership vacuum is so damaging. We’re staring at two years of a badly wounded, lame duck presidency suffering the whims of a protectionist, know-nothing, Democrat-led Congress. So waiting on the politicians is not an option. President Hu Jintao’s recent tour of America demonstrated this in spades: the deep warmth on the west coast segueing to the damp cool in the Bush White House.

That’s why business leaders must play a leading role right now in transcending the lack of strategic imagination currently afflicting Washington, first and foremost by framing the subject of China in the already looming 2008 presidential race.

I know my argument will strike many as naïve, but I don’t believe it’s naïve to trust greed over political ideology, either in America or in China. I trust people to be exactly who they are, and I expect the Chinese to remain Chinese.

I also expect greed to drive much of our debates on China here in the States. On one side, we’ll find protectionists and defense hawks offering all arguments imaginable as to China’s “inevitable” threats and treachery. They will seek to make money off your fear—or, in the case of Lou Dobbs, just pump up his ratings. On the other side, we’ll find corporations and investors offering every opposing argument imaginable as to China’s unlimited” potential and market. They will seek to make money off your hope—and your fondness for Wal-Mart’s low prices.

But rest assured, both sides seek to make money off China’s rise. It’s just a question of who cleans up the most. My immediate goal is to see our Army and Marines get the funding they need to survive the challenges of this long war, and so long as China is held up as the holy grail of the “big war” crowd within the Pentagon, that shift in priorities—from smarter weapons to smarter soldiers—will not come about.

My long-term goal is to harness China’s rise for something beyond the final assembly of our low-cost goods. I believe that something is to become the final assembler of low-cost countries, a market niche that sole military superpower America needs desperately filled right now.

America cannot deal with its strategic future until its leaders finally let go of its Cold War past. History will judge us all very harshly for wasting the strategic opportunity staring us in the face.

Friday, December 24, 2010 at 12:01AM

Friday, December 24, 2010 at 12:01AM