[Published in Mandarin by Knowfar Institute for Strategic and Defense Studies in Beijing, but available in original English only here]

America's Post-Oil Grand Strategy

by

Thomas P.M. Barnett

June 2015

The United States defaulted to a Middle East-centric grand strategy in the waning years of the Cold War and has remained stuck there ever since – sometimes in denial (like now) and sometimes in fervent embrace (George W. Bush and his neocons) but always in a manner that demanded some measure of White House attention. That seemingly unbreakable focus – particularly in relation to allies Israel and Saudi Arabia – now rapidly dissipates, falling victim first to a technological curveball and ultimately to a demographic shift that leaves Americans less willing to police the world and more interested in recasting their pursuit of happiness.

America’s political leaders have taken to describing this era as one of unprecedented uncertainty, but this is hardly the case. Globalization is either winning or has won across all the world’s regions, leaving only the question of which global “brands” (American, Chinese, Indian, European, Russian) will dominate where. President Obama and much of Washington now project the nation’s grand strategic ambitions in the direction of Asia, but they are mistaken. America’s historical scheme of integrating the world “laterally” (West to East) since World War II is largely complete, meaning these United States now enter an age of “vertical” integration (North to South) in the Western Hemisphere. This latitudinal expansion of the American System once imagined by our Founding Fathers will define U.S. foreign policy across the rest of this century.

The technological curveball that arrives just in time

In many ways, the hybrid U.S. economic system of big firms surrounded by a sea of small, technology-innovating start-ups represents the purest real-world expression of Karl Marx’s dialectic materialism – a theory of history that tracks causality from inexorable technological advance to altered economic reality to inevitable political change. What Marx never imagined was a political system able to structure itself so that those technological waves would just keep coming over the decades, consistently “buying off” the electoral acquiescence of the lower and middle classes in the face of elite domination (oftentimes real, sometimes just imagined) of the highest levels of government. In Marxian terminology, America’s political “superstructure” has learned how to co-evolve with its economic “base” better than any nation-state in history.

The feedback loop that has allowed that successful co-evolution is America’s sometimes stunningly permissive rule of law. Basically, you can try or invent just about anything in America that isn’t currently prohibited by law, whose construction trails innovation sometimes for decades. In too much of the rest of the world, one’s innovation and industry is limited to what is allowed by law. Do Americans pay for that permissiveness? Regularly – in the form of surges in criminality, environmental damage, labor abuse and sheer greed. But thanks to our participatory regulatory and legal systems, the “little guy” can fight back and can make those bastards pay for what they’ve done! So while the construction of protective laws trails crimes, disasters, and tragedies of the common, it never falls so far behind that the political system fractures – save for our unique historical experience with slavery.

Thus, it is only fitting that America’s historically recent Middle East-centric grand strategy, seemingly beholden as it was to the goal of assuring the world’s access to affordable energy, now falls victim to yet the latest in a long string of U.S.-triggered technological waves – the so-called fracking revolution. This silver bullet development, coming as it does just as two new, energy-import-dependent superpowers (China, India) rise in the East, could not be more fortuitous for extending the global moratorium on great power war begun with the invention of nuclear weapons. It essentially introduces enough slack in the world energy system to allow both Asian giants to step into their economic primes without needing to militarily challenge either the United States or its long-nurtured global trade system. When combined with the Western Hemisphere’s most crucial resource advantage – namely, arable land in an age of global climate change, America’s new-found energy independence fundamentally prevents any historical repeat of the structural run-ups to World Wars I or II, much less any revivification of the Cold War’s East-West destructive superpower rivalry. Thanks to fracking, it turns out that this town is big enough for the both of us – the U.S. and China in the Pacific Rim today, and China and India in Asia tomorrow.

Think about that for a minute: amidst all the continuing expert predictions of overpopulation and rising consumption bankrupting the planet to the point of non-stop “resource wars” among “thirsty” great powers (think oil and water), American ingenuity once again comes to the world’s rescue on both energy and food (i.e., water turned into human energy).

Just a decade ago, America imported almost two-thirds of its crude oil and entertained plans for new infrastructure to facilitate imports of liquid natural gas. Today it surpasses Saudi Arabia on crude oil production and, according to the U.S. Department of Energy, will become a net exporter of crude oil in roughly a decade’s time. Moreover, by tapping into what is estimated to be the world’s second-largest shale gas reserves (China is number one), America has re-vaulted itself to the leading ranks of world natural gas producers – soon available for export. This sort of technological turnaround is – quite frankly – just as impressive as China’s economic rise over the similarly long gestation period of the past quarter-century. But – again – more importantly, America’s technological achievement essentially solves the structural challenge created by China’s rapid ascension in the world power system – but only if both Washington and Beijing become smart enough to realize that.

President Barack Obama was absolutely correct in downsizing America’s “war on terror” from the Bush Administration’s focus on regime toppling to hunting down and killing bad guys. Frankly, that’s been America’s story on military interventions going all the way back to Panama and Manuel Noriega in 1989. We don’t take on governments anymore; we take on bad/nonstate actors (the Milosevic gang in Serbia, Al-Qaeda and the Taliban in Afghanistan, the “deck of 52” in Iraq, Qaddafi in Libya, and so on). By re-symmetricizing what has long been described as radical Islam’s asymmetrical war on the West, Obama right-sized the terror war. But to cover his soft-on-defense vulnerability as a Democrat, he coupled that wise decision with the strategically unsound declaration of America’s “pivot to Asia” – in effect, shifting from a region in which globalization’s advance is still being violently contested to one where its victory is already complete.

But here’s where the strategic irony grows stunningly disturbing: by attempting to contain rising China’s natural military expansion in East Asia, Washington inadvertently prevents what must become Beijing’s progressive embrace of the role of extra-regional security Leviathan for the Persian Gulf. Worse, by doing this, Washington actually encourages rival India to do the same when it must eventually partner with China in providing that regional security umbrella. In other words, just as America’s technological breakthrough on energy relieves it of its unwanted role in the Persian Gulf, Washington wrongheadedly works to prevent our historical relief from moving toward those “responsible stakeholder” roles.

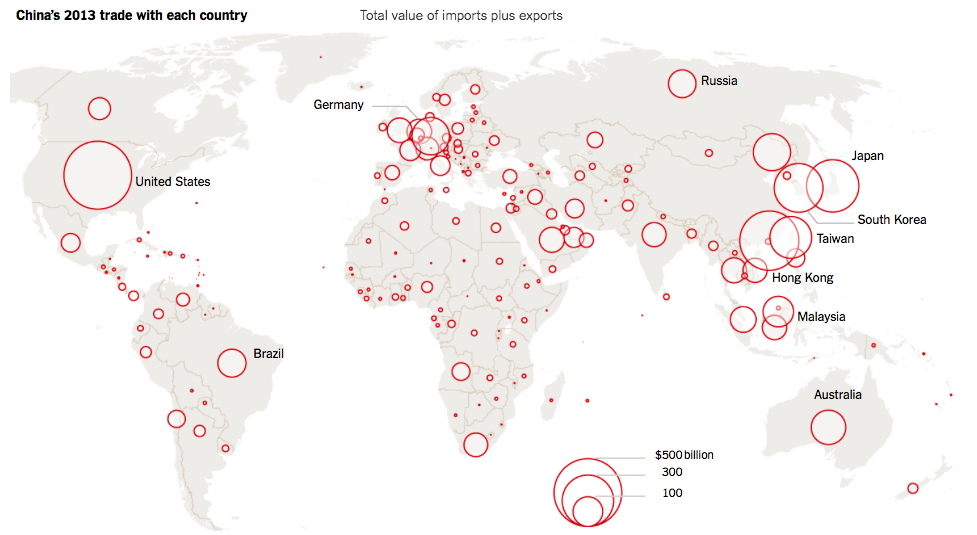

America’s Long(itudinal) War: It only gets worse

Understand this from the start: the Persian Gulf still matters to Europe in terms of energy flows but not to the United States. From the five top-10 global oil exporters located in the Gulf (Saudi Arabia, Iran, Iraq, UAE, Kuwait), only negligible amounts of crude oil currently flow to the Western Hemisphere. The vast majority of Persian Gulf oil exports (roughly four-fifths) flows into East Asia, with China and India alone accounting for half of that flow. Anti-war protestors got it only half-right: it may have been American blood, but it was never our oil.

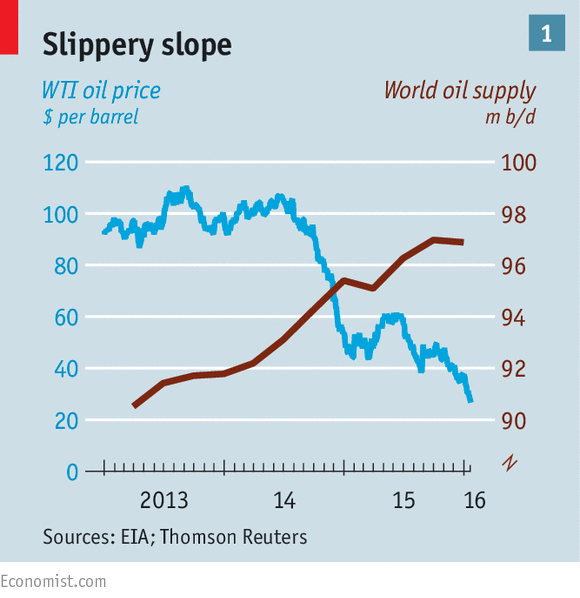

If you’re paying attention to Barack Obama’s second-term boldness in foreign policy, this newfound swagger clearly tracks back to a growing sense of both America’s energy independence and its ability to influence global energy markets. The recent bottoming of global oil prices was due in no small part to rising American production. In the case of Venezuela’s flagging financial support to Cuba, this left the Castro brothers more open to Obama’s offers of normalizing bilateral relations. In the case of Iran, this increased the White House’s confidence in moving ahead on the nuclear power deal – despite Riyadh and Israel’s obvious displeasure. Even in the case of Russia’s ongoing squeeze of Ukraine, the Obama Administration reveals no penchant for “blinking,” and why should it? The more Vladimir Putin isolates Russia from the West, the more Moscow is forced to sell off its vast natural resources to the world’s largest buyer of the same – those notoriously stingy and difficult Chinese. Putin’s reward for grabbing the Crimea is pitiable: the right to sell off Russia at bargain-basement prices to Beijing.

But make no mistake: there is genuine strategic risk in Obama’s mistimed Asian “pivot.”

In Asia alone, Washington risks a number of stumbling-into-great-power-war pathways, several of which could be driven by local powers (Japan and Vietnam especially) over-reacting to Beijing’s latest – literally – dredged-up beachhead or the right shooting incident between patrol craft operating above, on, or below the disputed waters. A rising superpower like China has wont of an appropriate whipping boy to demonstrate its growing military prowess. When America reached that jingoist apogee late in the 19th century, it was smart enough to target the comatose Spanish Empire in the Caribbean (Cuba) and Pacific (Philippines). For China, still nurturing regional grudges over past “humiliations,” East Asia is a sufficiently target-rich environment. And with the Pentagon locked and loaded to prove its AirSea Battle Concept, one cannot help but worry that some Asian variant of Archduke Ferdinand is now figuratively riding through the streets with his car-top down. Granted, the resulting shooting war is more likely virtual than real, but there too we find burgeoning cyber-warfare forces on both sides of the Pacific itching to press those keys and reveal to the world the damage they’re truly capable of inflicting.

Should the United States increasingly put at risk its greatest foreign policy achievement in history – namely, the rapid and planet-wide spread of our economic source-code (aka, globalization) – with this China-centric “pivot” to East Asia? No. In Beijing’s eyes, any U.S. effort to block their naval expansion leaves the Mainland vulnerable to military pressure from the sea – the oft employed attack vector of Western powers seeking China’s “humiliation.” All Americans have to do to approximate the average Chinese’s nationalism on this point is to imagine Chinese aircraft carriers, submarines and aircraft patrolling just beyond America’s declared national waters. Think of just how far Fox News could run with that.

Predictably – if not fortunately, crises in the Middle East routinely erupt to recapture America’s dangerously short strategic attention span. Here, the Obama Administration’s modus operandi of “leading from behind” is a preview of coming distractions. With Washington locally perceived as backing out of its longtime regional Leviathan role, and with relief (China, India) nowhere in sight, we collectively enter a nobody-is-minding-the-stove period in which the region’s preeminent three-sided rivalry between Saudi Arabia, Iran and Turkey will come to a dangerous boil.

We’ve seen this already unfold in the Islamic State’s frighteningly rapid rise. Fearing growing encirclement by the fabled Shia Crescent, Riyadh secretly bankrolled the group’s emergence in Syria and Iraq. Ankara, with similar rivalrous instincts, allowed Turkey to become a smuggling sieve for foreign fighters and supplies transiting to and from ISIS. Now, as their monstrous co-creation threatens them directly, both regimes are caught in the sort of strategic conundrum usually reserved for intervening extra-regional great powers – a truly telling development. Iran too now faces a certain imperial “overstretch” throughout the wider region, making its determined effort to gain international recognition as a nuclear power oddly reminiscent of the Soviet Union’s efforts with the West during the Cold War, in that, the more Tehran engages in great-power meddling of its own, the more it wants to erase the threat of possible strategic retaliation against the homeland – a decidedly logical move.

But it will be in the nuclear realm where this three-sided Gulf rivalry regularly rattles the world’s nerves in coming years. With Tehran on the verge of getting the Obama Administration to implicitly recognize its nuclear breakout capacity of a year-or-less, Riyadh is strongly rumored to be readying itself to cash in Pakistan’s long-offered promise of ready-to-use nuclear weapons. Meanwhile, Ankara, with NATO nuclear weapons already on its soil, will likely resist the temptation for now. Still, soon enough the world will find itself managing a three-sided nuclear standoff – however latent – among Israel, Iran, and Saudi Arabia. That prospect has to scare even the most fervent believer in the system-stabilizing effect of nuclear weapons, myself included.

Frightening as it may be for the world to re-learn the fundamental logic of mutually assured destruction – particularly in a region chock-full of End Times-embracing millenarians, I have spent the last decade proclaiming the inevitability of this pathway simply because Israel’s regional nuclear monopoly was always unsustainable and a bit spooky with its Masada complex. Now, the technological curveball that triggers America’s new strategic distance renders this outcome virtually inescapable. In nuclear terms, the inmates are finally running the asylum.

Go South, Young Man

America’s shift from a “horizontal” grand strategy (West integrating East) to a “vertical” grand strategy (North integrating South) is preordained by demographics. Any country’s economic rise stems first and foremost from an advantageous national age distribution, meaning lots of labor relative to children and old people. This “demographic dividend” is typically triggered by improvements in healthcare for mothers and young children, which allows families to eschew additional pregnancies out of the growing assurance that their first two or so children will make it into adulthood. That turning-off-the-fertility-spigot creates a welcome labor bulge that comes with a time limit of roughly a generation’s time – like the journey of America’s Boomer generation from youth to (now) old age. If you’re lucky, your society gets rich before it gets old.

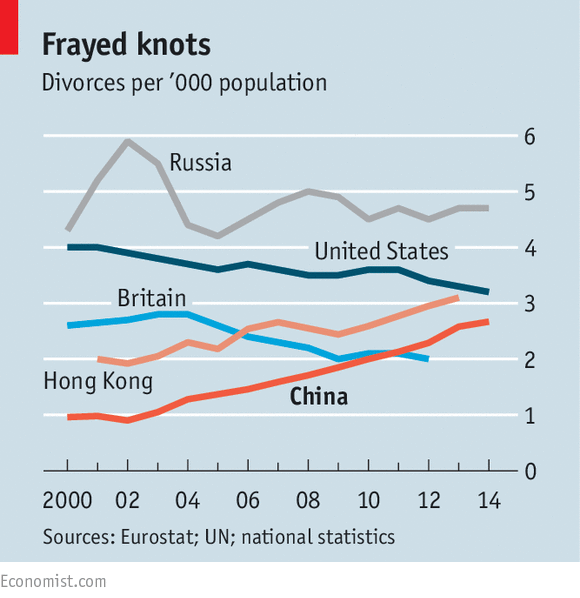

America took advantage of a fortuitous demographic dividend in the 1950s and 1960s to power the global economy with manufacturing. Compared to all of its competitors that suffered great loss of young life, the U.S. was overloaded with labor relative to dependents – a glorious run extended somewhat by the first Boomers’ arrival in the workplace in the mid-to-late 1960s. Japan was next to ride a lifting demographic wave, rising like a rocket across the 1970s and 1980s, only to see that trajectory fizzle out since the 1990s as the nation rapidly started stockpiling old people due to stunningly low fertility. China was next in the 1990s and 2000s, but then predictably saw its demographic dividend peak in 2010. Now, with fertility still low (the one-child policy became a hard habit to break), China will age (mean age) three times as fast as the U.S. through the middle of the century.

Whose up next? Southeast Asia enjoys a demographic dividend now, with India’s coming on its heels. Beyond them lay the Middle East and Africa, the latter looking at the biggest dividend that the world has ever seen (the better part of a billion people).

Why this economic history matters: Once a nation embraces manufacturing to leverage its demographic dividend, it starts “climbing the ladder of production,” moving from cheap and assembled goods to higher-order manufacturing. A rite of passage is seen in automobile manufacturing, which dovetails with any rising economy’s growing middle-class demand for mobility. As it climbs that ladder, the nations in question must slough off their lower-end manufacturing to those countries coming into their own demographic dividends. In short, these nations become inexorably bound to their successors through direct investment and integration via expanding global production chains. In many ways, then, the shifting center of gravity in the global economy’s cheap-labor surplus is a magnificently integrating and thus pacifying historical force. China, for example, needs Southeast Asia’s demographic dividend to work for its own long-term economic health. In the end, that’s the biggest brake on Chinese regional militarism.

Which brings us to why America must turn its welcoming gaze southward – now.

America is the Dorian Gray of great powers. We’ll age far more slowly than the rest of the West and even most of the advancing East over the next several decades precisely because we enjoy immigration pressures from Latin America – a far younger and faster-growing region than North America. Demographically speaking, the two most important factors in economic growth are slowing social aging and integrating one’s economy with younger and faster-growing neighboring economies. For the U.S., that’s Latin America, which is why America’s long-standing policy of focusing its foreign policy attention everywhere else in the world but Latin America must end, along with our nation’s highly costly and destructive “war on drugs” – a process thankfully begun in terms of individual states decriminalizing marijuana use.

You may be thinking: shouldn’t America contest China’s spreading influence in places like East Asia, Central Asia, the Middle East and Africa? The answer is no, for all the economic integration reasons cited above. Good example: China and Africa are simultaneously engaging in a massive urbanization wave, giving Chinese construction companies clear economies-of-scale advantages in that vast building scheme. Yes, American companies can and should be part of that build-up process, but we cannot hope to compete with the Chinese for influence brought about by progressively deeper economic integration. America’s great accomplishment during its demographic heyday was to trigger and nurture and defend Asia’s integration into the global economy. Now it’s Asia’s turn to extend that historical process to most of the remaining South – but not Latin America if the U.S. plays it smart.

With climate change making the planet’s middle lattitudes increasingly inhospitable over this century, migratory pressures will grow. In choosing between heading south (Argentina, Brazil, Chile) or heading north (North America), most Latinos will continue to head north – as they should. In terms of underutilized arable land, upper North America offers far more economic potential than South America’s southern cone. Today America grows wheat in water-starved Texas. By mid-century we’ll be growing it in water-rich Alaska. No kidding.

Right now, one out of six Americans is Latino. By mid-century, Latinos will approach a one-third share of the U.S. population – and voters. Already, Miami is the de facto social and economic “capital” of Latin America – a sign of political integration to come.

No, adding new stars to the American flag won’t unfold as some modern, militaristic imperialism. Instead, led by its largest demographic cohort ever – those Millennials, these United States will get back in the historical business of attracting and accepting new members. Remember, we began this journey of integration as a confederation of 13 colonies (1789), growing over the next 170 years to our current total of 50 states. That’s averaging a new member roughly every half-decade. Then we shut that door following the admissions of Hawaii and Alaska (non-contiguous states, it must be noted) in 1959, adding nothing since. Do you want America to stay competitive with those billion-person Asian behemoths China and India? Well, the Western Hemisphere contains roughly a billion souls.

When America’s Founding Fathers dreamt of an American System of political, economic, social and territorial integration, they weren’t just contemplating our horizontal slice of North America. Visionaries like Alexander Hamilton and later Henry Clay (who coined the term) imagined that system extending itself to welcome all Americans.

The U.S. remade the world over the last seven decades by spreading its system of rules and economic model. Globalization was a “conspiracy” hatched by Washington and it’s been called many things over the decades, from Teddy Roosevelt’s “open door” to Franklin Roosevelt’s “new deal for the world.” Having successfully led that integration process from West to East, it’s now America’s duty – and self-preserving opportunity – to build out that American System across the entire Western Hemisphere.

And that process needs to begin now – as in, the next president.

Monday, October 22, 2018 at 9:14PM

Monday, October 22, 2018 at 9:14PM  Today I confirmed with Knowfar leadership that we won't proceed beyond the three-year research-fellow deal that I agreed to back in 2015. As recently as last spring they indicated a desire to have me teach a research methodology class to their network of foreign-affairs and security experts, but that sort of ambition seems to have dried up amidst the worsening of US-China relations this year. Knowfar, which had surprised me somewhat in the past with its willingness to push the envelope on acceptable topics for discussion (e.g., they had me analyze Xi Jinping's decision to abolish presidential term limits), now seems decidedly more circumspect in its research agenda. The institute doesn't need me for that pathway, so it makes sense to part ways.

Today I confirmed with Knowfar leadership that we won't proceed beyond the three-year research-fellow deal that I agreed to back in 2015. As recently as last spring they indicated a desire to have me teach a research methodology class to their network of foreign-affairs and security experts, but that sort of ambition seems to have dried up amidst the worsening of US-China relations this year. Knowfar, which had surprised me somewhat in the past with its willingness to push the envelope on acceptable topics for discussion (e.g., they had me analyze Xi Jinping's decision to abolish presidential term limits), now seems decidedly more circumspect in its research agenda. The institute doesn't need me for that pathway, so it makes sense to part ways.