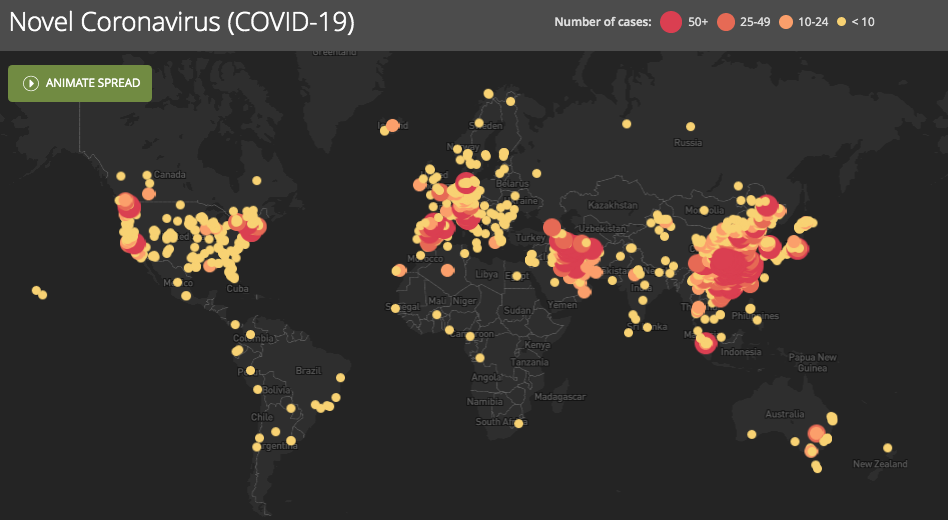

The coronavirus reminds us just how connected our world is, how there's no going back, and how this is the nature of crisis in the age of globalization

Monday, March 16, 2020 at 11:45AM

Monday, March 16, 2020 at 11:45AM  When I wrote my trilogy of books (Pentagon's New Map [2004], Blueprint for Action [2005], Great Powers [2009]), my primary purpose was to explore and explain what I thought was the new nature of crisis and conflict in the world.

When I wrote my trilogy of books (Pentagon's New Map [2004], Blueprint for Action [2005], Great Powers [2009]), my primary purpose was to explore and explain what I thought was the new nature of crisis and conflict in the world.

In the first instance, it is about globalization's rapid and penetrating embrace of lesser connected countries, or what I dubbed the Gap. By and large that is a great thing (reduction of global poverty, creation of first-in-history truly global middle class), but it's very disruptive of culture and tradition and power structures, and conflict (largely in the form of state and non-state resistance to all this rising and intrusive connectivity) ensues. That's why I called it the Pentagon's new map, my argument being, this is the nature of crisis and conflict.

The terror strikes of 9/11 represented that sort of new crisis: actors targeting symbols of connectivity (trade, security) and hoping to trigger a self-isolating effect (West leaves the Middle East). West, instead, came in force, triggering all sorts of refugee flows, revolutions, crackdowns, civil wars, etc. West got tired and now it's mostly the East working this problem, but the connectivity continues and grows - both good and bad.

As my previous post indicated, Y2K was, for me and many others, a scheduled practice-like glimpse into these dynamics of system perturbation as the defining form of international crisis (vertical shocks followed by long horizontal waves of impact).

Since 9/11, we've had the Great Recession and a variety of lesser pandemics. Now we're finally confronting the long-anticipated killer pandemic that is coronavirus - the first great replay of a Spanish Flu-like transmission under the conditions of modern globalization.

How are we handling it? Actually, pretty much like expected.

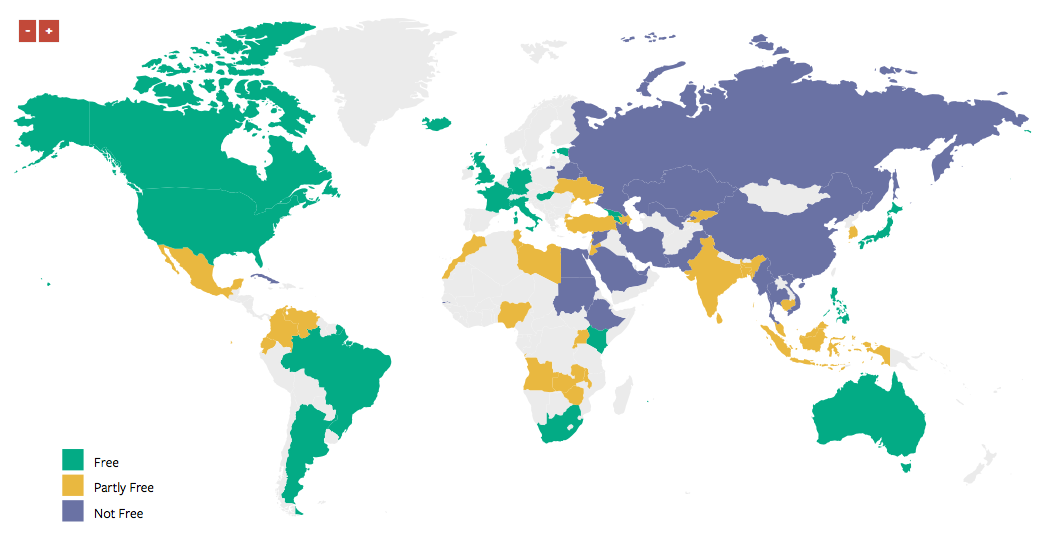

Authoritarian countries seek to hide or minimize the situation, while democracies are slow to act despite mounting evidence. This is to be expected. Vertical power systems like China know how to handle horizontally spreading crises like this through traditional means of centralized control. Once the initial vertical shock passes (Wuhan for China), vertical systems tend not to fear horizontal dynamics. They are built to suppress such dynamics. Vertical systems really fear the out-of-the-blue stuff at the beginning because it triggers that popular emperor-has-no-clothes realization that all dictators fear so intently.

Instead, it's the horizontal political systems (like US and democracies in general) that tend to struggle more with the follow-on horizontal scenarios like this. We see the vertical shock of Wuhan in the distance and we blow it off (too far away, nothing to do with us). Then we start noticing the horizontally travelling shock waves approach through the world's many networks. But, given our system and culture, we fear the imposition of vertical controls ("evil Washington," "black helicopters," "take my guns" and other fantasies) that oftentimes work best right off the start, and so - over time - we suffer being the land of a 1000 different responses. Who's in charge? Hard to say. News comes in from all angles (POTUS, CDC, Congress, governors, mayors, school districts, etc.). The broken-clock preppers are right again! And the rest of us fight the inner panic urge.

While that decentralized approach, at first, seems to makes the problem worse (and it can alright), over time, our horizontally-defined strengths emerge. Our horizontally-structured system is free to experiment across the board, and our free press (even under conditions of political polarization) are adept at discovering, critiquing, and spreading best practices as they emerge (God bless them, one and all). In the end, our horizontal political structures will tighten up some (centralize), but not wildly so, and they tend to re-relax over time as the crisis fades in memory and legal remedies ensue.

But lessons will be learned, and we will structure aspects of our polity, economy, networks, etc., to account for what we've learned. And yes, it will make us better next time.

The larger lesson that remains is the same one we've been learning for two-to-three decades now, or since the end of the Cold War freed our minds to look at our connected/connecting world without the overlay of the superpower conflict/great-power war paradigm: our modern world is defined by connectivity, which grows over time and sets the parameters of all meaningful crises and how we respond to, and grow from, them.

Yes, we may think we can unilaterally withdraw from that world - however selectively or broadly, but that's a myth.

Yes, we may think we can renegotiate all the terms of our connectivity with the outside world, and, while we can certaintly adjust, that's a multi-sided game now with all sorts of great powers trying the same trick at the same time, so rule-set clashes proliferate. These clashes are far from traditional conflict, but they do represent those powers realizing that, now that globalization is here, that is the best way to fight for what you want - or believe in.

Since 2016 America has sought to withdraw from the world, and it hasn't gone all that well. Our ability to set agendas, dampen great power tensions, or steer developments has been hugely diminished. So has the global appeal of our rule-sets, which we spent the previous seven decades advocating for, and spreading, around the planet. We are a much smaller power in the world right now, and we're increasingly nervous about that, because the world hasn't grown any simpler as a result.

The coronavirus crisis exposes the folly of our recent approach (The Wall being our most hilariously sad example), more saliently than the still-dismissable (in too many minds) slow-mo climate change crisis (which certainly drives the uptick in zoonosis transmission events [animals-to-human disease vectors] by pushing humanity and wildlife together in more disruptive synergies).

And so corona does us this favor: it reminds us of how far we've come in this globalization and how going-your-own-way is a fear-threat reaction beneath our standing as a long-time global leader and - indeed - the primary architect of the world we still find ourselves in.

And so we learn again about the nature of our globalized world, the threats it poses and the crises it generates, and - hopefully - we once again reconsider our recent slide toward fantasizing about the return of conventional/strategic great-power war as a possibility (or, more insanely, as an inevitability) and we re-embrace what we re-learn everytime we endure one of these vertical-shocks-triggering-scary-horizontal-waves ...

Namely, that we are all in this together, and increasingly defined by our global connectivity.

We can try to shape that hardening reality for the better, or we can stick our fingers in our ears and scream nonsense in an effort to block this reality out. In our worst fears, we can always retreat to nostalgia, demanding that the homogenous world-of-our-youth magically return. But frankly, along that path lies not only self-delusion of the Osama Bin Laden sort but also the political violence that pathetic neediness begets.

But that world is gone, and that America is gone. What has replaced both is something far better, full of far more freedom, acceptance, diversity, and tolerance that what came before - yes, even despite our predictably frightened behavior of the past few years.

That new world/new America simply requires new and better skills. And the coronavirus is just another experience that will generate, teach, and codify those lessons and skills.

And it will make all of us, our nation, and this world stronger (or, if you must insist - greater).

Thomas P.M. Barnett Comments Off |

Thomas P.M. Barnett Comments Off |  System Perturbation,

System Perturbation,  globalization | in

globalization | in  Blast From My Past |

Blast From My Past |  Email Article |

Email Article |  Permalink |

Permalink |  Print Article

Print Article